A European (dis)Union

“What is going wrong in the European Union these days?” is probably the question that many European voters have been trying to answer in the past few years and all recent events keep pointing at it. First, the recent showdown between Bundesbank President Weidmann and ECB President Draghi on fiscal policy reminded us that even the monetary union, though initiated first to trigger political union, remains a far from smooth cooperation. Second, the theme of (im)migration has been at the very core of the Brexit campaign and added to the overall dissent among European political leaders. This brings us to a last topic of politics at the European level that will be key to deliver solutions.

In such a dense context, the 14th BGSE Economics Trobada 2016 ended up with a very much welcome roundtable focused on “The Future of Europe” and chaired by Professor Jaume Ventura. To help us understand better these various challenges for the EU and its future, Professor Ventura gathered the affiliated Barcelona GSE professors Fernando Broner, Julian di Giovanni and Giacomo Ponzetto.

Breaking the Bank and Bailing out States: Finance in the EU

By Fernando Broner

European Financial Markets

Professor Broner first presented the financial structure of European capital markets, in opposition to that of the United States. Notably, he highlighted that while equity markets play a greater role than banking sector assets in the US, the relation is more than inverted in the EU where banking sector assets are almost six times the size of equity assets.

Equity markets are regulated by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), founded only recently in 2011. As pointed by Professor Broner, this young regulator still suffers from weak coordination which restrains its action and thus the extension and deepening of European equity markets. Similarly, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), adopted in 2002 to bring a unified framework and hence foster equity markets, has not been fully enforced. On top of these regulatory inefficiencies, two more reasons also weigh on European equity markets: a strong home bias (64% of EU and 61% of Eurozone equity is held domestically) instead of more interconnections between European countries; as well as the fact that banks mostly lend to each other through debt instruments.

Despite European banks having large activities abroad (18% vs 9% in the US), they are smaller and less diversified, in comparison to their American competitors. However, Professor Broner noted that the crisis prevention framework was today better articulated, under the ECB’s Single Supervisory Mechanism and an improved interaction between the European Commission and the European Banking Authority (EBA) at the rule-making level. The picture is less positive though for crisis management due to responsibilities shared at both the national (lender of last resort, deposit insurance) and European level (Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) and European Stability Mechanism (ESM)).

Sovereign Debt and Bail Out control

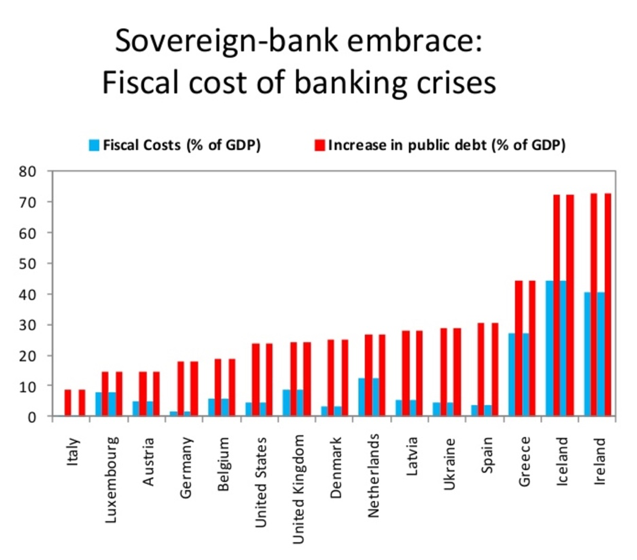

Professor Broner then turned to sovereign debt, another highly sensitive topic for the EU. Prior to the global financial crisis, sovereign risk had almost disappeared in the Euro-area as spreads for all countries were trading in the same range. Part of this decline and convergence in spreads could be explained by expectations of “automatic” bail-outs and a higher cost of default, which proved both inefficient and inaccurate. Along the Eurozone debt crises, various packages were set up to address bail-outs: at the beginning the International Monetary Fund was very active along with European countries and progressively took a step back to let the EU new financial institutions (first the European Financial Stability Facility then the ESM) take over and manage the bail-outs packages. Even the ECB has been directly involved with its Security Markets Programme enacted in 2010 to purchase mostly sovereign bonds. Professor Broner highlighted the unclear role of the ESM: it is similar to a bank capitalized by Eurozone members, whose priority is to provide liquidity. However, it remains criticized by some countries as it offers a kind of transfer scheme, notably through its high maturity loans at very low interest rates. Another challenge is the “sovereign-bank embrace” generated by the current institutional setup, with Eurozone banks holding more and more government bonds. This has serious implications as it crowds out lending to the private sector and reinforces banks’ exposure to sovereign risk while reciprocally banks’ exposure affects also government on the fiscal side as the cost of banking crises significantly participated to the sharp increase of public debt ratios of these countries.

Source: Professor Broner’s presentation

Professor Broner concluded his presentation with some recommendations for the future of European finance. First, remaining barriers to international diversification in the equity markets should be removed. Second, banks’ risk sharing should be improved by encouraging more equity exposure as well as consolidation across countries with more regulation of banks’ subsidiaries. Finally, there should some disincentive action against the current sovereign-bank embrace trend with a direct lender of last resort scheme, direct ESM funding for recapitalizing banks and limitations to the sovereign exposure.