The Political Future of the European Union

By Giacomo Ponzetto

The next session moved on to the political economy of the EU. Professor Ponzetto started his presentation by sketching the classical theory of fiscal federalism that gives insights on both the current state of the EU and its future.

This theory boils down to the trade off between the benefits of policy coordination and the costs of policy uniformity: is there too much (for example many economists agree that the agricultural pact went too far; the same goes for monetary union with less consensus) or too little (since there is a monetary union, fiscal union needs to be achieved) coordination in the current European framework? The cost-benefit analysis becomes even trickier when the size of the union kicks in: with whom should we coordinate? Is the European Union overstretched, should it continue to expand to new countries? Over time a neoliberal consensus has emerged, embodied by the research work of Alberto Alesina (1999, 2005), pointing at a union that is too small and homogenous. This union has also seized the control of too many policies: this research tells us that any decision maker will take control of a policy whenever he has the possibility, whereas some policies would be best kept off limits as voters do not necessarily agree to delegate them. Furthermore, no matter it does too much or too little, the European Union is doing it wrong according to this neoliberal consensus: the single market is too little enforced, and so are the public goods (failure of coordination of foreign policy, defense); on the other side, it does way too much redistribution and local public services.

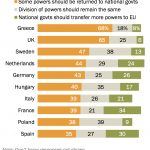

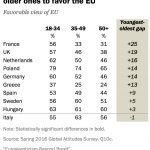

Professor Ponzetto highlighted two different scenarios for the future of Europe in the context of global economic integration. In the continuity of Brexit, the first possible outcome is that globalization renders the EU irrelevant, up to its dissolution, since its main realization, the single market, loses its competitive advantage with rising global trade. Here members no longer need to bear the cost of uniformity. On the contrary, it could also strengthen the European Union thanks to the very same single market. It could be the appropriate tool to take advantage of rising trade opportunities and common economic regulation that fosters economic integration as noted by Gancia, Ponzetto and Ventura (2016). In any case, Brexit may offer a natural experiment to check which of these scenarios is correct. Looking at qualitative data published by the Pew Research Center before the vote offers a mixed picture: the short term agreement on an “ever closer” union looks is a stretch, while it could change in the long term as younger adults are more likely to favour the EU.

Source: Euroskepticism Beyond Brexit, Pew Research Center, June 2016

The presentation then turned to the topic that really complicates European Union’s relation to voters: shared responsibility and political accountability. In practice, the EU has exclusive control on a very limited number of policies. Though a flexible combination of European and national responsibility seemed beneficial (Alesina, Angeloni and Etro, 2005), it also generated opacity and loss of accountability (Joanis, 2014): who is responsible for policy outcomes? This question enabled politicians to blame the European Union and holding it responsible for any policy failure. As such, a better enforcement of accountability through clear delegated monitoring would be welcome. Boffa, Piolatto and Ponzetto (2016) found that differences in government accountability (for example Germany versus Italy) make the union more desirable by helping countries converge to the best practices. Political economy also tells us that a fiscal union does not seem very likely to happen for two reasons highlighted by Persson and Tabellini (1996): moral hazard in local policy (higher risk taking); and the fact that risk sharing entails redistribution (not in theory but always in practice). It also provides some other insights on the hostility to immigration through three factors: labour-market competition (see Professor di Giovanni’s presentation), pressure on the welfare state and xenophobia.

Gazing into his crystal ball, Professor Ponzetto concluded his presentation by reminding us that the EU remains very cautious and does not aim at grand reform. On the positive side, the single market will probably go forward and continue to deepen, in particular for the European financial markets. On the negative side, he remarks that the current (and old) inefficiencies will probably continue for quite some time. Also, barring a significant shift in German politics, the fiscal doctrine is not likely to move from austerity to pro-competitive reforms.

References:

Alberto Alesina, Ignazio Angeloni, Federico Etro, 2005. “International Unions”, American Economic Review

Federico Boffa, Amedeo Piolatto & Giacomo A.M. Ponzetto, 2016. “Political Centralization and Government Accountability” Quarterly Journal of Economics

Marcelin Joanis, 2014. Shared Accountability and Partial Decentralization in Local Public Good Provision. Journal of Development Economics

Gino Gancia, Giacomo Ponzetto, Jaume Ventura, 2016. “Globalization and Political Structure”, NBER Working Paper No. 22046

Torsten Persson, Guido Tabellini, 1996. “Federal Fiscal Constitutions: Risk Sharing and Redistribution”, Journal of Political Economy

Bruce Stokes, Euroskepticism Beyond Brexit, Pew Research Center, June 7, 2016