With Donald Trump voted in as the 45th US President, the world economy has witnessed another sobering reminder of the rise of populism, inward-looking politics and a sweeping anti-establishment wave, having barely recovered from the last with Britain’s vote to leave the EU. Initial market turmoil from Trump’s surprise victory last Thursday has reversed, as fiscal stimulus takes centre stage on Trump’s economic agenda, but does the Trump plan have what it takes to kick-start the US economy?

“We have a great economic plan, we will double our growth and have the strongest economy anywhere in the world” was the promise made by US President –elect Donald Trump; to “make America great again”. Having won the confidence of millions of Americans, against a backdrop of stagnant productivity, weak wage growth and rising inequality, Trump’s “great economic plan” has a lot to deliver.

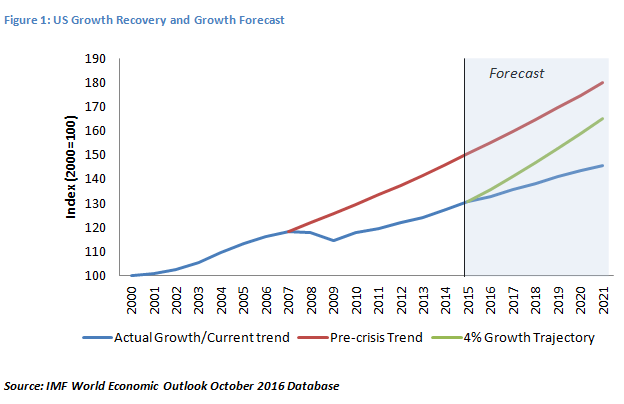

With the US economy having grown a little over 2 per cent on average over the last six years, and forecast to grow slightly under for the next six[i], doubling of current growth would require something quite extraordinary. Even compared to pre-crisis growth of 3 per cent per year in the decade preceding the financial crisis, this target looks ambitious. If achieved, however, the US economy could close over half of the shortfall compared to its pre-crisis trend by 2021, as in figure 1.

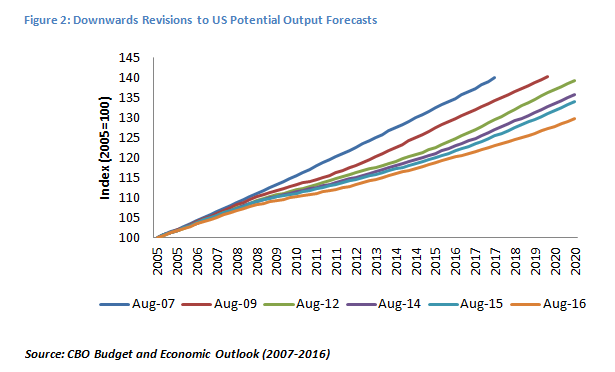

The challenge then becomes finding new drivers of productivity growth to boost economic activity, and lifting lacklustre demand. Since the financial crisis, this has proven difficult, despite ultra-loose monetary policy. Moreover, growth in potential output has failed to materialise during the recovery, as evident in the US Congressional Budget Office’s consecutive downwards revisions to US potential output since 2008, as in figure 2. Figure 2 has come to be closely associated with an idea that the weak recovery may have at its heart a more structural rather than cyclical cause, also known as Secular Stagnation.

The Secular Stagnation Hypothesis

The term secular stagnation was initially coined by Alvin Hanson in 1938, in the aftermath of the Great Depression, questioning whether demand would be sufficient to support future economic growth. After over 70 years, former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers revived this debate, after observing the weak economic recovery in advanced economies despite historically low interest rates. Summers suggests that the real interest rate, required to keep full employment and balance investment and savings, may actually be negative.

This may be due to a chronic shortfall of demand from a lack of productive investment opportunities and a build-up of savings, driven by demographic factors such as ageing populations or a fall in the relative price of capital. Moreover, with advanced economies experiencing low levels of inflation, boosting demand by reducing real interest rates becomes more difficult with monetary policy becoming ineffective at the zero lower bound, shifting the onus to fiscal and structural policies to support economic growth

The secular stagnation hypothesis finds some support in the evidence, with the real interest rate observed to be declining since the early 2000’s[ii]. However, former US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke interprets this as evidence of a temporary or cyclical “global savings glut”[iii]. Considering the open economy, he suggests excess savings have built up due to large current account surpluses held by oil producing and emerging economies. As Bernanke emphasises the root of the problem matters for the policy prescription: a structural demand deficit (under Secular Stagnation) may require a fiscal expansion, while a temporary excess or imbalance of savings would be best addressed through increasing mobility of international capital flows.

Weak growth – a global problem

The challenges of weak growth and productivity are not solely faced by the US. Similar trends have been observed across advanced economies such as the Euro Area and Japan, with potential output consistently disappointing to the downside[iv]. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook published last month revised down again forecasts for growth in advanced economies, to 1.6 per cent in 2016 and 1.8 per cent in 2017, down by -0.5 and -0.3 percentage points from start of this year alone. Furthermore, the IMF warned that “persistent stagnation in advanced economies could further fuel anti-trade sentiment, stifling growth”.

The “great economic plan”….

As it slowly emerges and gains coherence, Trump’s economic plan is a cocktail of fiscal expansion and trade protectionism. In theory, a package of tax cuts and deregulation should incentivise more investment by lowering the marginal tax rate on investment returns. This could provide a pivotal boost to the US economy – provided it doesn’t break the bank first. The Tax Policy Centre estimates a sizeable increase in national debt, by almost 80 per cent [recently revised down to 50 per cent] of GDP over the next 20 years[v], with benefits most likely only for the highest income earners.

Moreover, notable economists including Larry Summers and Adam Posen have criticised the package for being “ill-designed”[vi], providing tax cuts which are likely to be “low-multiplier rather than high-multiplier and budget-busting rather than responsible”[vii]. Worse still, if these tax cuts are funded through cuts in more productive spending such as research & development or education, they could actually undermine growth.

Trump’s protectionist stance on trade would also drag on growth with severe implications for the global economy. Campaign promises of 45 and 35 percent import tariffs from China and Mexico could result in a trade war, and end up costing the US economy 4.8 million[viii] jobs, while tougher foreign investment rules could worsen the “global savings glut”. As the election campaign did not fail to shock and surprise, so developments across these areas continue to present both upside and downside risks, with some forecasters even predicting a recession by the start of 2018[ix].

Don’t forget the Fed

US equity markets, which once dived at the prospect of Hillary Clinton losing, have since rallied over the prospect of Trump’s fiscal expansion plans, while government yields continue rising with expectations of inflationary pressures to follow. With the US economy already close to the 2% inflation target and near full employment, there is a strong case for interest rate hikes starting in December. But as the Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen warned, a series of aggressive rate hikes could stall growth, pushing Trump’s doubling of growth target even further out of reach. Much of the success of any fiscal expansion will depend on multipliers and the associated monetary policy response (to be explored in an upcoming post), and as Yellen emphasised a great deal of uncertainty still surrounds the proposed economic policies. For now at least, ‘Trumponomics’ seems unlikely to be the solution to our secular stagnation problems.

References

[i] IMF World Economic Outlook, “Subdued Demand: Symptoms and Remedies”, October 2016

[ii] King, M., & Low, D., “Measuring the World Real Interest Rate”, NBER Working Paper w19887

[iii] Bernanke, B., “Why are interest rates so low, part 3: The Global Savings Glut”, Brookings, April 2015

[iv] Summers, L., “Reflections on the new ‘Secular Stagnation hypothesis”, VOXEU, 30 October 2014

[v] Nunns., J et al., “Analysis of Donald Trump’s Tax Plan”, Tax Policy Centre Research Report, December 2015

[vi] Gurdus, E., “Larry Summers: Trump’s economic plan is ‘ill-designed’ and harmful”, CNBC, 16th November 2016

[vii] Acton, G., “‘Trumponomics’ is unfunded, open-ended and kind of ridiculous, economist Adam Posen says”, CNBC, 16th November 2016

[viii] Nolan, M., et al. “Assessing Trade Agendas in the US Presidential Campaign”, Peterson Institute for International Economics, September 2016

[ix] Zandi et al, “The Macroeconomic Consequences of Mr. Trump’s Economic Policies”, Moody’s Analytics, June 2016