As a European liberal and free-trade advocate, it has become quite entertaining to skim through social media, opinion pages, or listen to conversations about the latest tariffs imposed by the U.S. administration. One cannot help but wonder why a large fraction of Europeans, who just three years ago where protesting on the streets across all major European cities against the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the infamous U.S. chlorinated chicken, are now the ones running their mouth about how “ignorant,” “stupid,” and “dangerous” Donald J. Trump’s decision to impose steel tariffs is. Surely, a lot of this has to be attributed to the very person associated with the tariff. It seems unlikely that people who regularly blame “neo-liberal” politics for the demise of literally everything are now in favor of a liberal stance on free trade and see a trade war as a threat to the welfare of the world.

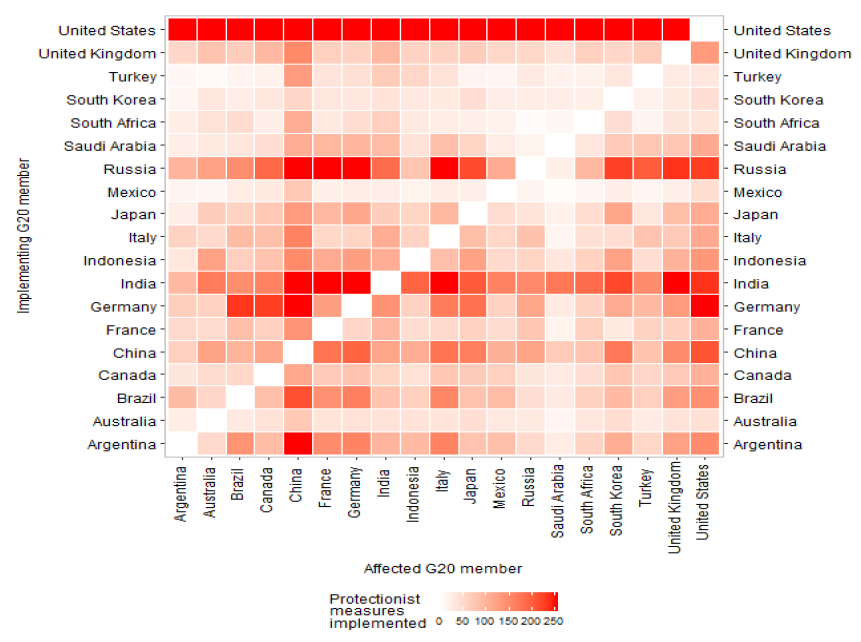

Whatever one’s personal opinion about the 45th President of the United States is, we should acknowledge one thing: He is not alone in putting up trade barriers. Contrary to recent common belief, it’s not only Donald Trump who’s the biggest threat to increased welfare through global trade but also Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and the European Union. If you counted the latter, you already know where this is going: G20.

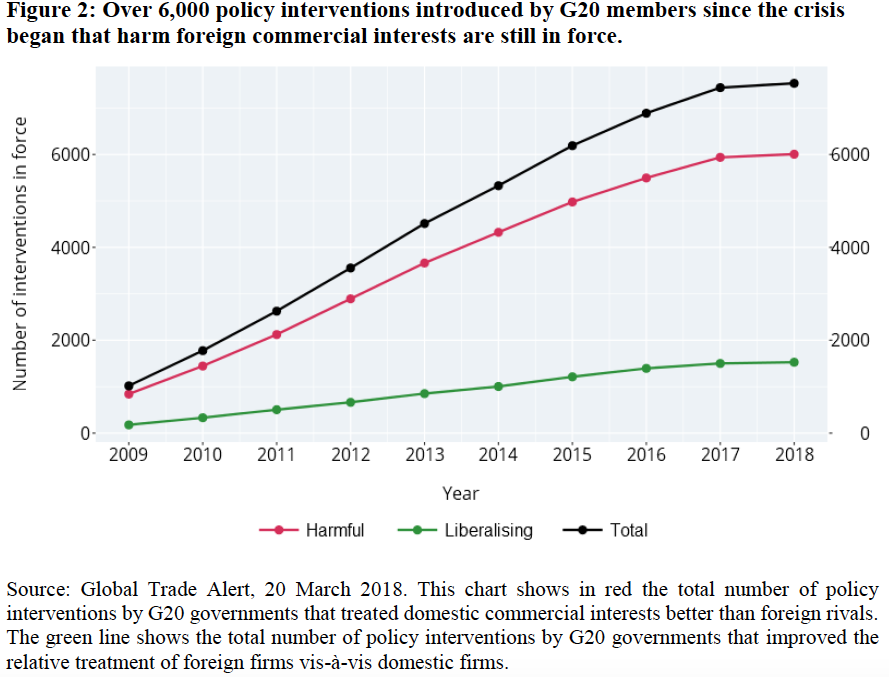

A recent policy brief addressed to the G20 members and their policymakers by Evenett[1] et al. (2018) shows this clearly. The policy brief states that over 6,000 interventions introduced by G20 members since the crises of 2009 that harm commercial interests are still in force. This is quite remarkable given the responses of the G7 members to the refusal of the United States to stand behind a common declaration of the recent sitting condemning protectionism. Moreover, it is in direct contradiction to the G20 summit declaration of 2008 and 2009, which posits that the G20 governments reject protectionism.

Further, the policy brief holds some uncomfortable truths for free-trade advocates as well as for globalization critiques. The former might be surprised by the extent to which trade barriers have grown since 2009, whereas the latter might be dazed by the consequences these barriers have on the least developed countries (LDCs).

Since the Great Recession and the financial crises of the late 2000s, trade barriers have risen sharply. Data gathered by Global Trader Alert, which has the most comprehensive coverage of all types of trade-discriminatory measures according to the IMF, indicates that a total of 200-250 new policies that harm foreign commercial interests have been implemented each quarter by G20 governments since November 2008. This amounts to a staggering 6,842 distortions to global commerce. It is imperative to emphasize that only 34% of them were outright import and export restrictions that a non-economist would normally think of when asked about trade barriers. Almost half of the trade distortions involve some type of state aid (e.g. subsidies, export incentives, and the like). Figure 2 of Evenett et al. (2018) summarizes this trend in the state of trade distortions by G20 members.

Notwithstanding, the picture of who imposes trade distortions is quite heterogeneous. Figure 3 of Evenett et al. (2018) gives an impressive graphical presentation of the reciprocal nature of the trade distortions of G20 members vis-á-vis each other. The heat map also unmasks one of Trumps notorious lies, or ignorance, i.e. that the United States is the “fair player” in global trade and that the world is cheating them. From the figure it is evident that since 2009 the U.S. has established a high number of protectionist measures across all G20 member countries, whereas only Germany, India, and Russia seem to have the same level of reciprocal measures against the U.S.. Poster children of free trade are emerging market economies like Turkey and South Africa, whereas the long-standing free-trade advocate United Kingdom is only somewhere in the upper third of free-traders. Unsurprisingly, the country which suffers the least from protectionist measures is Saudi Arabia, given its status as the world’s largest oil producer.

Using fine-grained UN trade data, the authors are able to identify to what extent these distortionary measures are affecting the export of goods of G20 members:

- The percentage of G20 goods exports facing harmful policy acts has risen from 40% in 2009 to 80% in the first quarter of 2018.

- Close to 9% of G20 goods exports compete in foreign markets where import tariffs have been raised.

- Just under 19% of G20 exports compete in foreign markets against subsidies or bailed out domestic firms.

- 75% of G20 exports now compete in foreign markets against foreign rivals that are eligible for some sort of state export incentive (mostly through incentives in the national tax systems).

- 79% of LDC’s goods export compete in foreign markets against trade distortions implemented by G20 countries.

Where the final point should be emphasized. The trade distortions that LDCs face in exporting to G20 countries are also present in the competition on third country markets, further limiting the growth and development prospects of the poorest of the poor. Moreover, if the developed countries go ahead with this kind of policy and less developed countries adapt to this new state of the world by imposing trade distortions, we might end up in a bad equilibrium where less developed countries are excluded from global value chains.

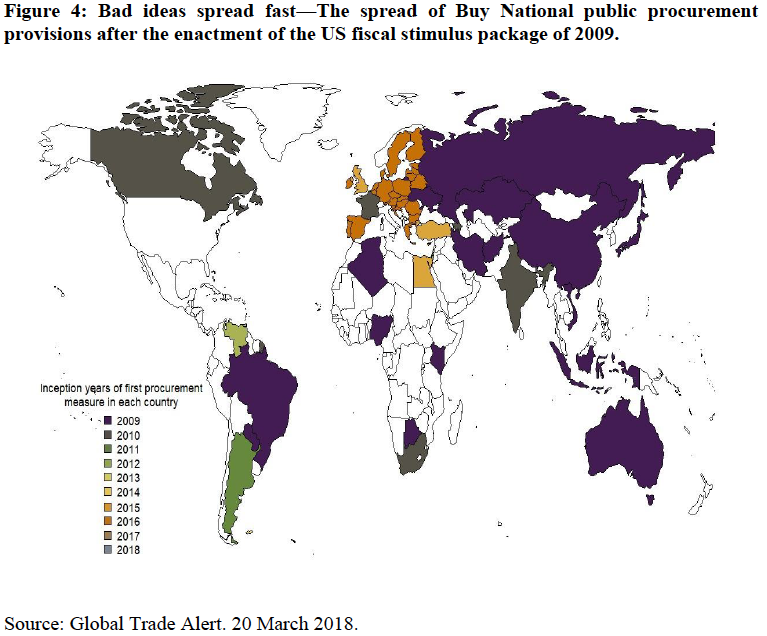

We actually see this already happening. In the wake of the financial crises, the U.S. whipped up a massive fiscal stimulus to help their economy (and ours!) recover. However, the stimulus package had a provision that demanded that public procurement should buy national, effectively putting up a huge barrier to import goods. Figure 4 of Evenett et al. (2018) shows how fast this idea spread around the world. Almost all of the other G20 countries followed suit and so did some developing countries. Policymakers might think this kind of procurement provision helps their national industries, however, they have to take into account that it also might have a negative effect on the government budget through higher prices, because domestic producers do not face international competition.

If we want globalization and trade to be inclusive and lead to sustainable growth and development even in the least fortunate parts of the world, we must acknowledge that the trade barriers the G20 put in place are detrimental to this effort.

The policy brief by Evenett et al. (which includes two proposals to reverse the dangerous path we are on) can be obtained here.

[1]Simon J. Evenett is Professor of International Trade and Economic Development at the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland, and Co-Director of the CEPR Programme in International Trade and Regional Economics. He gives Policy Lessons on the international trade systems to students in the ITFD programme.