Editor’s note: This post is part of a series showcasing BSE master projects. The project is a required component of all Master’s programs at the Barcelona School of Economics.

Abstract

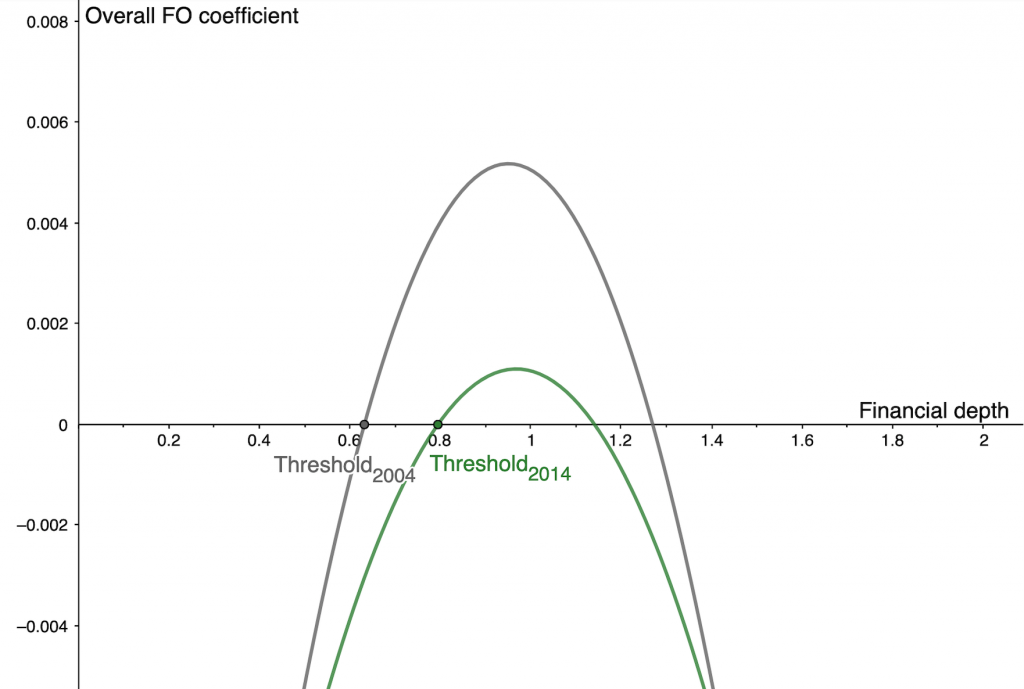

Is financial globalization beneficial to economies at all levels of development? Or are there certain “threshold” levels of financial, institutional and economic development a country must first attain in order to realize the growth benefits of globalization? Kose, Prasad and Taylor (2009) develop a unified empirical framework to answer this question. The debate on the literature is ongoing. Yet few studies have explored these questions in a post-crisis context. In this paper, we replicate and extend their work, paying close attention to the period 2005-2014. Our analysis yields three key results. First, the financial depth threshold above which countries can benefit from financial globalization increases from 66% to 81% when we consider the extended period. Second, the proportion of countries with depth levels above this threshold declines over time. Finally, the coefficients are smaller in absolute value over the period 1975-2014. Taken together, these results imply a breakdown in the relationship between financial depth, openness and growth since the Great Recession. Financial deepening on its own can no longer ensure positive growth effects of financial integration.

Conclusion

In the paper, we examine two periods 1975-2004 and 1975-2014 and test for threshold effects in three variables, financial depth, institutional quality and trade openness. This paper is unique in its inclusion of the years immediately before and following the Great Recession. Following a surge in international financial integration between 2005 and 2007, financial openness plummeted with the onset of the crisis in 2007. This effect was most pronounced in advanced economies. As economic growth rates declined, countries turned their backs on financial globalization. Financial flows have since rebounded, albeit not to their pre-crisis levels. The effect of this volatility on the relationship between financial openness and economic growth however is not well understood.

We analyze changes in the financial depth threshold over time as well as changes in the proportion of countries with depth levels above this threshold over time. We present three key findings. We first document an increase in the threshold level of financial depth from 66% to 81% when we extend the period to 2014. It follows that the proportion of countries with levels of depth above this threshold decreases over time. Our estimate of 66% for the period 1975-2004 is remarkably close to that of Kose et al. Secondly, the coefficient estimates are smaller and less significant which points to a breakdown in the relationship between financial openness and growth in the post-crisis period. Finally, we identify significant threshold effects of institutional quality.

Together these results point to a weaker relationship between financial openness and growth in the post-crisis period. Our estimates suggest that once a country reaches the threshold level of financial depth, further improvements in depth stop being important quite rapidly. It is now more difficult for countries to attain the benefits of financial integration, not just because the threshold of financial depth is higher but because financial depth alone may no longer be sufficient to ensure growth. The trade-off that further financial deepening can generate between higher growth and a higher risk of crisis needs to be addressed. The Great Recession was a reminder that financial depth and financial stability need not go hand in hand. The risks of financial deepening are more evident than before. Focusing only on the long run growth view overlooks this trade-off. In order to conduct policy relevant research, a new approach that realistically accounts for both the growth and crisis effects of financial deepening is required.

Authors: Eimear Flynn, Florencia Saravia, Josefina Cenzon, Nimisha Gupta, and Selena Tezel