Editor’s note: This post is part of a series showcasing BSE master projects. The project is a required component of all Master’s programs at the Barcelona School of Economics.

Overview

Using a dynamic panel fixed effects model, we find that increases of ODA of above 2% of GDP have significant effects on the economic growth of African countries in the immediate aftermath of severe natural disasters. This is a surprising result because we do not find that ODA in times of relative stability has a significant effect on GDP. This suggests that debt relief, at least through the channel of significant increases in ODA, is an effective instrument in promoting post-disaster recovery, even though its effectiveness in raising economic growth more generally is limited. Since increases in ODA inflows of above 2% of GDP only occurred after 1/3 of the disasters we studied, we recommend that international financial institutions concentrate ODA flows on countries that had been afflicted by severe disasters.

Introduction

One of the biggest challenges facing developing Sub-Saharan African economies is their vulnerability to severe natural disasters such as droughts and floods. Not only do they face on average over 50 disasters a year, but their economies’ over-reliance on agricultural production and weak institutional capacity cause them to experience the effects of these disasters particularly acutely. Worryingly, this vulnerability is likely to rise in the coming years, as the earth warms and climate change increases the number and severity of extreme climatic events.

While it is difficult for countries to prevent natural disasters, since they tend to arise from exogenous climate conditions, they can take steps to mitigate these adverse consequences through post-disaster rehabilitation. To do so, governments require sufficient fiscal space so that they can borrow and spend without jeopardising budgetary sustainability. However, many African countries suffer from persistently high levels of debt, with 33 of the 39 countries in the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries scheme located on the continent. This constrains government spending on humanitarian relief and reconstruction, which can leave countries unable to recover from the devastation.

In view of these twin trends – African economies’ vulnerability to natural disasters and their crippling levels of debt – any channel that reduces a country’s debt burden and hence increases its fiscal space should theoretically encourage faster economic recovery. This suggests that debt relief can be a vital policy instrument in mitigating the negative effects of natural disasters. However, corruption and inefficient resource allocation mean that its effectiveness may be constrained in practice. To explore the role of debt relief further, we employ a dynamic panel fixed effects model across the most severe 25 floods and 68 droughts in Africa from 1978 to 2013. As a robustness check, we also include an Anderson-Hsiao style GMM estimation procedure. We define debt relief as any policy that reduces the need for governments to issue new debt or repay existing debt, particularly in the aftermath of a natural disaster. In the context of this paper, this includes debt forgiveness, debt rescheduling and/or increased official development assistance (ODA). Furthermore, we run two different specifications of debt relief: first, using a dummy variable which indicates any instance of the aforementioned forms of debt relief; and second, using a continuous variable for ODA inflows alone.

Main findings

Surprisingly, when we run our first specification, we find that debt relief in general does not have a statistically significant impact on economic growth. Additionally, ODA inflows in times of relative stability do not have significant effects on economic growth. Instead, they only reduce debt-to-GDP growth, suggesting that they are merely used by governments to pay off existing debt. This is in line with previous research by both Mejia (2014) and Raddatz (2009), who found at most weak evidence that either debt relief in the aftermath of disasters or ODA in general is effective in boosting economic growth.

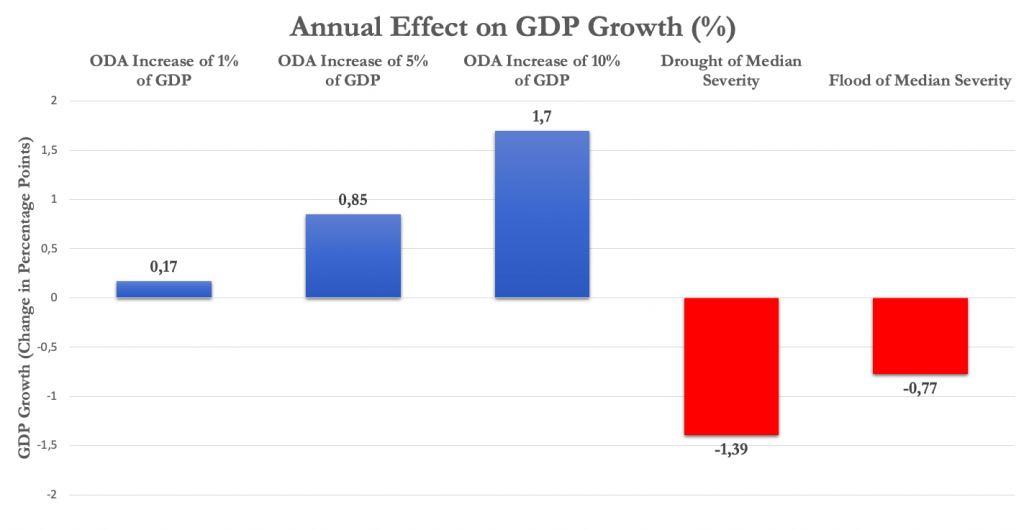

In contrast, we find that increases in inflows of ODA of above 2% of a country’s annual GDP, when provided in the year of or immediately after severe disasters, do have statistically significant positive effects on economic growth (see Figure 1). These findings are similarly observed when we interact our ODA variable with the continuous measure of disaster severity. For a given level of ODA, the effectiveness of post-disaster ODA increases in the severity of the underlying disasters. Furthermore, ODA inflows no longer have statistically significant effects on debt-to-GDP growth. This suggests that, unlike in regular times, ODA flows are used fruitfully by governments after disasters to bolster economic recovery rather than to pay off existing debt.

This is a notable result because it suggests that debt relief, at least through the channel of ODA, is an effective instrument to promote post-disaster recovery. This result differs from that found by previous research because we focus on ODA increases that a) were larger than 2% of GDP and b) occurred in the aftermath of severe natural disasters. This helps us isolate the specific role of ODA in promoting post-disaster recovery from its general effectiveness as a form of economic stimulus to boost growth.

Policy implications

Our findings suggest that policymakers in international financial institutions such as the OECD or IMF should step up efforts to increase ODA inflows to developing countries when severe natural disasters hit. This not only has the direct effect of reducing the loss of lives, but is also vital for poverty reduction by ensuring that these countries return rapidly to their existing balanced growth path. Otherwise, countries risk experiencing persistent economic slowdown and skyrocketing debt due to the disasters, which would in turn lead to a vicious cycle of mounting debt and stagnant growth. Instead, increased ODA flows can substitute for the domestic shortfall in resources available to countries to rehabilitate the economy by providing emergency relief to citizens and rebuilding damaged infrastructure.

Current attempts at mitigating such disasters are relatively limited: in our sample of 92 severe disasters in Africa between 1978 and 2013, large increases of ODA greater than 2% of GDP only occurred after 32 of these disasters. This is surprisingly infrequent, especially considering that we focus only on the largest of disasters which should have ample international media coverage. As highlighted above, larger increases in ODA have greater cumulative effects on the economy, especially for more severe disasters. As this effect is not observed when we study ODA inflows in times of stability or inflows below 2% of GDP, we recommend that existing ODA programmes prioritise large flows to countries which have just suffered from severe natural disasters. This is because the marginal benefit of these targeted flows in promoting development is likely higher than general flows to countries that are relatively stable.

Finally, although our paper focuses on floods and droughts in Africa, we believe that our results can be generalized to other types of disasters. Although further research is needed to fully establish the causal mechanism by which debt relief improves post-disaster outcomes, it is likely that it will have a similar positive impact in rehabilitating economies that face disasters which leave them with high levels of debt and significantly lower budgetary revenue. Most notably, it suggests that significant increases in ODA flows can play a vital role in helping developing economies devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic by allowing them to mitigate its adverse effects.

References

Mejia, S. A. (2014, July). Debt, Growth and Natural Disasters A Caribbean Trilogy (IMF Working Papers No. 14/125). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/imf/imfwpa/ 14-125.html

Raddatz, C. (2009). The Wrath of God: Macroeconomic Costs of Natural Disasters. The World Bank. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/wbk/wbrwps/5039.html

Connect with the authors

About the BSE Master’s Program in International Trade, Finance, and Development