Editor’s note: This post is part of a series showcasing BSE master projects. The project is a required component of all Master’s programs at the Barcelona School of Economics.

Introduction

Our work focuses on the analysis of the Venezuelan banks, which have become more vulnerable. The leading causes of this vulnerability have been oil price shocks, political instability, pro-cyclical monetary conditions (i.e., interest rates), low level of financial intermediation, changing structure (e.g., consolidation, closure or nationalization), non-traditional bank transactions, high exposure to the public sector, and government intervention in their operations. (Blavy R., 2014) Hence, studying the response of banks to policy uncertainty becomes relevant. However, even more critical, in Venezuela’s context, would be to ask: do banks respond differently to uncertainty if they are politically connected?

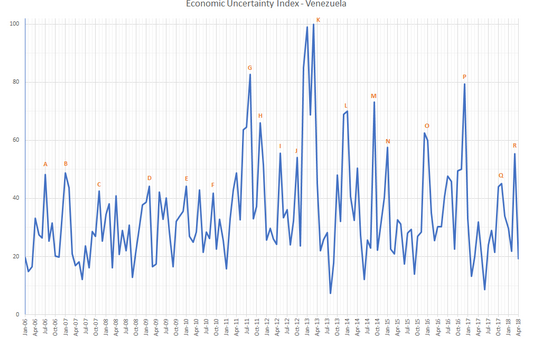

To address this question, we construct two indices: the policy uncertainty index and political connection index. Our uncertainty index is in a monthly basis and bank-invariant; it is developed following the work previously done by Baker, Bloom, and David, on the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index (EPU Index) and by Ahir, Bloom, and Furceri, on the World Uncertainty Index (an extension of the EPU). Similar to Xu and Zhou (2008), for the case of the political connection index, we define the dummy variable connected bank equal one based on whether it is a state-owned bank. Alternatively, in case it is a private one if at least one of the board members has any connection with someone from the government. We adapt these criteria to the information there is available from Venezuela. We also look if one of the members is part of the ‘bolibourgeoisie’ ( a combination of the words Bolivarian and bourgeoisie, a term used to classify the businessmen and public officials linked to the government). For our dependent and micro-control variables (i.e., bank characteristics), we use monthly data from 2006 to 2018 obtained from SUDEBAN (Venezuela’s Superintendence of Banks). Moreover, for the macro-control variables, we obtain monthly data from the International Financial Statistics of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The variables we choose for our specifications are based on the works done by Vera et al. (2019) and Bordo et al. (2016).

Our central hypothesis is that when there is high policy uncertainty, political connections may allow connected banks to smooth the effects of uncertainty. We believe that connected banks might respond differently to uncertainty because they have privileged information or preferential treatment from the government, which grants them a competitive advantage over non-connected banks. To test the response of banks, we look at their behavior respect to credit supply and provisions, and we also investigate banks’ profitability in periods of uncertainty through the ROA. Our identification strategy to investigate the causal effect of policy uncertainty and political connection considers the fact that the uncertainty index is a high-frequency time series, which makes it be almost an exogenous variable. Also, the political connection index is not endogenous as it does not vary over time.

In addition to that, we control for bank-invariant and time-specific factors that affect both the right-hand side and left-hand-side variables by adding bank and time fixed effects. Furthermore, to separate the impact of our primary explanatory variable (interaction) from other confounding factors, we control for a block of bank-specific covariates. We also consider different specifications with and without lags of these controls to mitigate the potential reverse-causality concern. Even though we know that all of these adjustments might not entirely correct for omitted variable bias, we consider it adjusts well enough to investigate this relationship. We consider that one of the significant sources of potential bias comes from monthly macro changes (i.e., exogenous shocks like oil prices or U.S. sanctions, and government decisions) that are accounted by including time fixed-effects.

Results

In our main results, we find that politically connected banks acquire more risks when there is higher uncertainty as an increase of 10 percent in our uncertainty measure leads them to give on average, 0.0262 percent more credits than non-politically connected banks. This result corroborates similar results from the literature that establishes a positive value from being politically connected (Kostovetsky 2015). Also, we observe that an increase in the uncertainty index induces politically connected banks to hold more loss provisions in their portfolio than non-politically connected banks. A 10 percent increase in our uncertainty index prompts politically connected banks to hold 0.0192 percent more loss provisions than non-politically connected banks. Lastly, the effect of economic policy uncertainty for politically connected banks on ROA has a positive sign. A 10 percent increase in uncertainty increases the average returns on assets of politically connected banks by almost 11 percent compared to non-politically connected banks.

Summing up, connected banks can give more credit to the public in periods of higher uncertainty, at the same time that they hold more loss provisions. The first result is consistent with the ones shown by Cheng et al. (2017), where they find that banks supply much more credit when there is high uncertainty. However, our result of provisions does not coincide with theirs. Contrarily, they find that under higher uncertainty, connected banks reserve lower provisions than unconnected banks. In the case of the profitability analysis, connected banks have lower profits when there is high uncertainty. These results go along with the ones found by Dicko (2016).

We consider that this study presents new relevant findings regarding the literature of political connection and policy uncertainty, and for the Venezuelan economy overall. The political connection matters in periods of high uncertainty but until one point. From our results, we find that politically connected banks seem pro-risk as they give more credit when there is more policy uncertainty. However, on another level, it appears that they do receive privilege information form the government (bad news about the future) that makes them risk-averse at the same time as they also reserve more provisions. Additionally, the result of the relationship between uncertainty and profitability indicators, like ROA, indicates that being politically connected might not be extremely helpful to banks if they only benefit from having more information and do not receive any tangible benefit from the government. For further studies, it would be interesting to analyze how economic agents respond to policy uncertainty depending on the type of benefit they receive from being politically connected to some institutions.

About the BSE Master’s Program in Economics of Public Policy