Maximilian and Elliot connected through social media due to the Barcelona GSE connection and started working together on this piece due to shared research interests.

The COVID-19 pandemic is changing the way that we live our lives. As time passes it is becoming apparent that even once the lockdown policies have been eased and some level of normality has been resumed, the new world that we live in will be different to the one we knew before. This article focuses on emerging trends within the UK that have largely taken place as a result of COVID-19, or in some cases the pandemic has simply accelerated a trend that was already occurring. We then look to offer a range of public policy solutions for the recovery period where the overarching objective is to increase wellbeing in society in a sustainable way. These are focused towards the UK but several could be paralleled to other advanced economies.

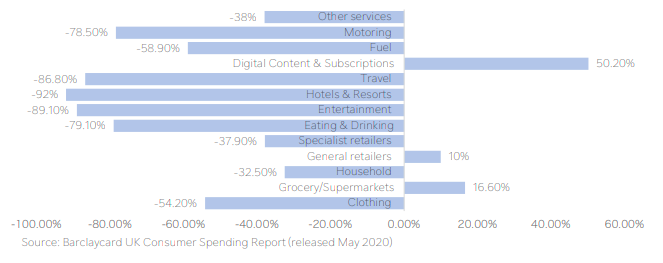

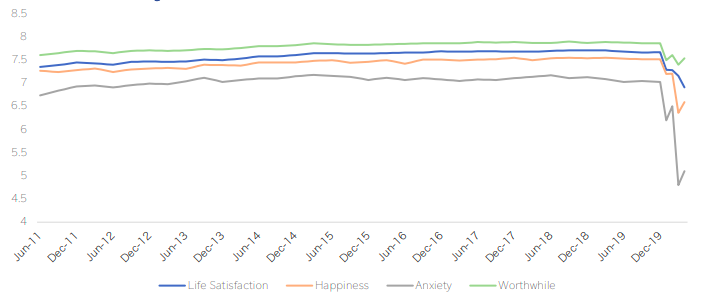

But first, before we get to the policy solutions, briefly, what have been the main economic and wellbeing effects that we have seen as a result of COVID-19? In 2020, it is expected that the fall in overall economic output is going to be larger than during the financial crisis in 2008. Much of this is due to the level of decline in economic activity as a result of the UK governments lockdown policy. This was a necessary decision in order to reduce the spread of the virus and ensure the health service still has capacity to treat those that have unfortunately caught the disease. However, it has led to a significant liquidity shock for both households and businesses. Large portions of the labour market are now out of work and levels of consumer spending have declined rapidly (Chart 1). Alongside sharp falls in measures of economic performance, measures of wellbeing have declined rapidly as well (Chart 2). Increases in measures of uncertainty have mirrored increases in anxiety. While, social distancing policies are having a large impact on measures of happiness.

Source: ONS. Notes: Each of these questions is answered on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is “not at all” and 10 is “completely”. Question: “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?”, “Overall, to what extent do you feel that the things you do in your life are worthwhile?”, “Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday?”, “Overall, how anxious did you feel yesterday?”.

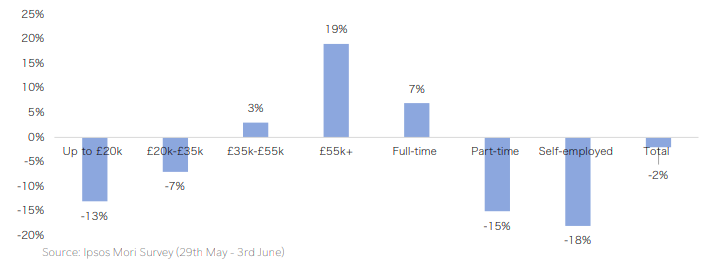

The UK government responded to the shock posed by COVID-19 with a range of policy interventions to provide funding to those that have been most impacted. At a macro level, the long-lasting effects of this crisis will be more pertinent if economic activity does not respond quickly after the government’s schemes have ended. Large portions of UK businesses have limited cash reserves to fall back on in a scenario where demand remains subdued for some time. However, even if the recovery period is strong there will still have been some clear winners and losers during this crisis. Younger workers, those on lower incomes and those with atypical work contracts are the ones that have been most heavily impacted (Chart 3). Whilst those on higher incomes, that are more likely to be able to work from home, have increased their household savings during this period, due to less opportunities to consume.

The policy solutions outlined below aim to be complementary of one another and look to amplify observed trends that are positive for wellbeing and to provide intervention where trends have been negative for wellbeing:

- Climate at the centre of the response: This is less a policy recommendation and more a theme for the response. However, our message here is that increased public spending projects, focused towards green initiatives should be combined with a coherent carbon tax policy which influences incentives and helps to support the UK’s transition to a low carbon economy.

- Labour market reforms: The government should look to develop a centralised job retraining and job matching scheme that supports workers most impacted by COVID-19, helps to encourage structural transformation towards emerging industries and increases the amount of highly skilled workers in the UK workforce.

- Tough decisions on business: Some businesses will require further assistance from the UK government in the form of equity funding, rather than the debt funding seen so far. This should be done on a conditional basis, requiring all these businesses to comply with the UK’s climate objectives and should only be provided to businesses in industries that are expanding or strategically important to the UK economy.

- Modernising the regions on a cleaner, greener and higher level: Looking to build on the governments ‘levelling up the regions’ policy to reduce regional inequalities, our policy consists of government funded infrastructure policies that include green investments for regions outside of the UK’s capital.

- Harbouring that rainbow effect: Building on the increased community spirit that has been observed during the pandemic, this policy solution looks to increase localised community funding to maintain social cohesion and support those with mental health issues.

Lastly, as the policy recommendations focus on expanding public investment to support the recovery, it is important to consider what this means for public debt sustainability in the UK. The conclusion is that as a result of the low interest rate environment, the most efficient way out of this recession is to borrow and spend on projects that will increase resilience to future shocks and support the UK’s transition to a low carbon economy.

Please click on the link below to read about this in more detail. Comments are welcome.

Full article originally posted on Exploring Happiness.

Elliot Jones ’18 is a Sovereign Credit Risk Analyst at the Bank of England. He is an alum of the Barcelona GSE’s Master’s in Macroeconomic Policy and Financial Markets.

Maximilian Magnacca Sancho ’21 is an incoming student in the Barcelona GSE Master’s in International Trade, Finance, and Development.