Marco Antonielli ’12 (International Trade, Finance, and Development) is a consultant with Nathan Associates in London. Prior to this he was a consultant at the OECD in Paris and a research assistant at the Bruegel think tank in Brussels. The following piece by Marco originally appeared on Nathan’s website. (All opinion and analysis are only those of the author.)

Marco Antonielli ’12 (International Trade, Finance, and Development) is a consultant with Nathan Associates in London. Prior to this he was a consultant at the OECD in Paris and a research assistant at the Bruegel think tank in Brussels. The following piece by Marco originally appeared on Nathan’s website. (All opinion and analysis are only those of the author.)

Follow Marco on Twitter @AntonielliM and read his blog.

In a global economy with fewer opportunities to industrialize, low-income countries will need to embed the service sector in their vision for inclusive growth.

Amid a gloomy global economic outlook and crashing commodity prices, low-income countries ended 2015 with the slowest growth since 2009, and remain in serious need of new sources of inclusive growth. One major challenge to achieving higher living standards stems from the vast income and productivity gaps within these countries and in relation to the rest of the world.

Large-scale industrialization has traditionally been viewed as the main solution for bridging these gaps, as well as a strategic objective to create jobs and support future growth. Yet latecomers to development may have embarked on a path on which manufacturing—arguably the most promising sector—is expanding slowly in absolute terms, and often shrinking in relation to GDP. The questions are then: why do low-income countries struggle to industrialize? And could alternative sectors such as services replace manufacturing as engines of inclusive growth?

Growing out of the Traditional Economy

Let’s take a step back. While all economies are characterized by varying degrees of productivity and dynamism among sectors and businesses, the low-income countries feature tremendous structural gaps within their economies. Most of the workforce is employed in informal and traditional agricultural businesses, while manufacturing is limited and not fully organized and the dynamic services are largely confined to the cities. Also the modern and formal agricultural businesses are not as widespread as they could be.

To escape poverty, millions of workers need to move from low-productivity sectors and businesses, mainly agriculture, to high-productivity ones, where they will find better and more secure jobs. The reallocation of resources to modern and dynamic sectors can generate positive transformation and help low-income countries achieve inclusive growth.

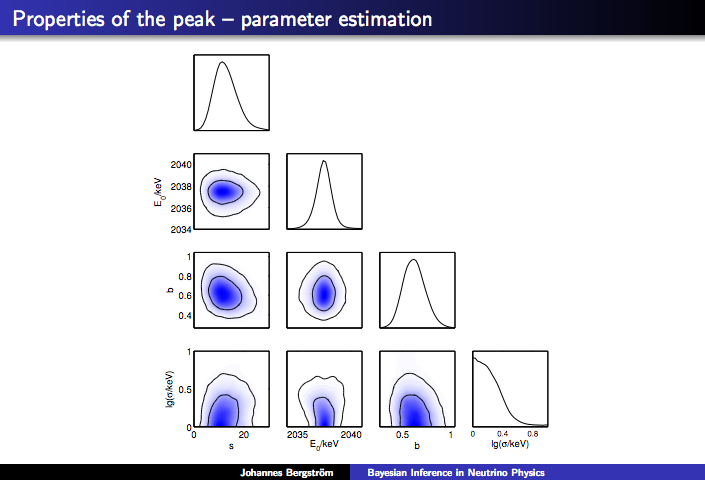

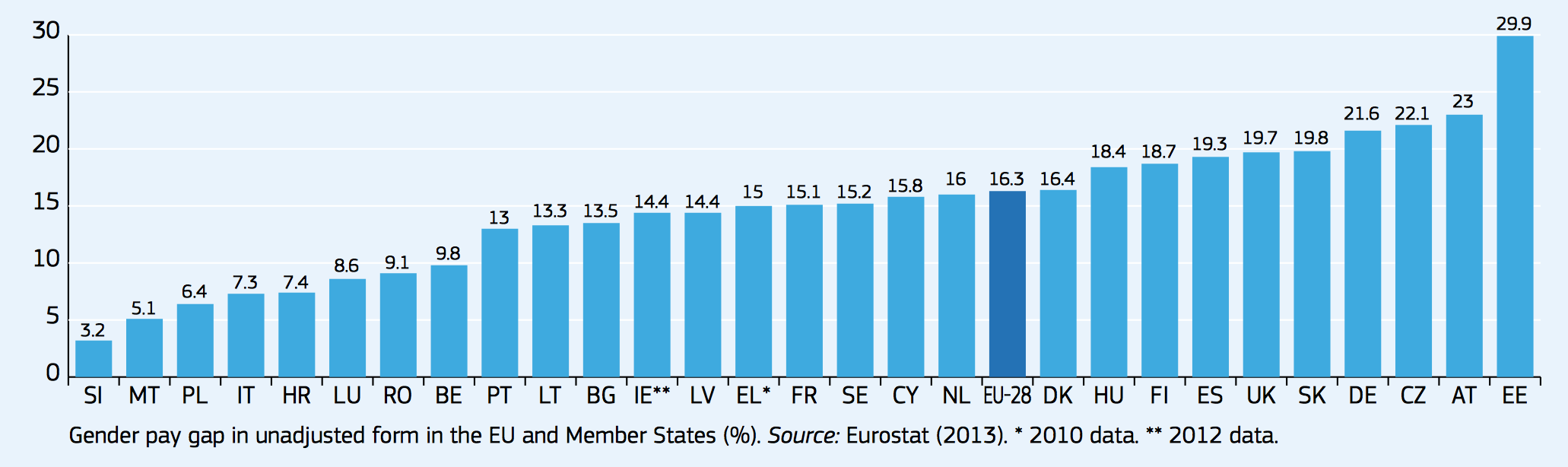

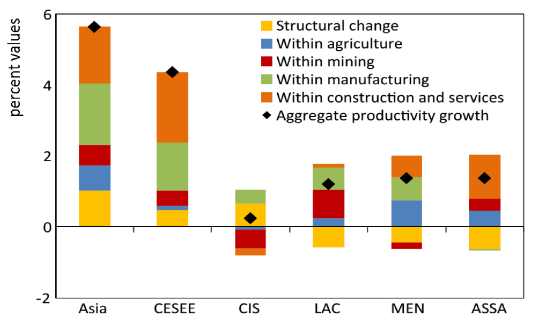

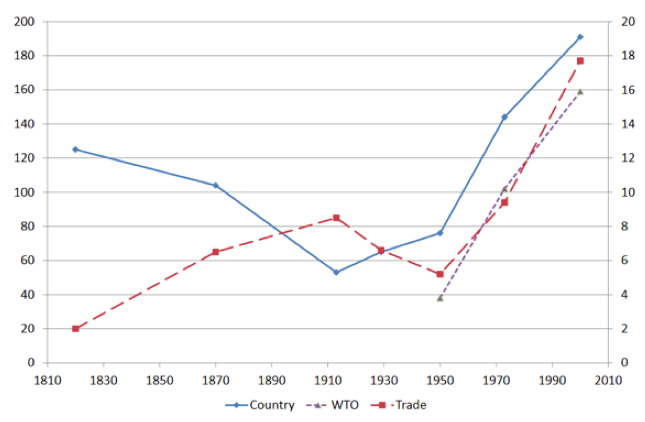

However, economic transformation can lead to labor and capital being reallocated to more inefficient activities. Recent studies have found that from a macroeconomic perspective, structural transformation (i.e., intersectoral movement of resources) can be a drag on growth for long periods of time, and this is part of the reason why the growth dynamics of low- and middle-income countries have been so diverse. Such a pattern is illustrated in figure 1. Observing the breakdown (“decomposition”) of aggregate productivity growth in the sum of sectoral components and a component accounting for cross-sectoral labor reallocation, it can be noted that between the 1990s and the 2010s Asian and Eastern European countries benefited from the structural transformation of their economies, while Latin American and Sub-Saharan African countries had the opposite experience. Developing countries are therefore not necessarily transforming well over their growth paths.

Figure 1—Decomposition of aggregate productivity growth, 1990–2008

Source: Dabla-Norris et al. (2014)

CESEE: Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe; CIS: Commonwealth of Independent States; LAC: Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA: Middle East and North Africa; SSA: Sub-Saharan Africa

Organized and modern manufacturing is commonly understood as the business where workers in informal or more traditional forms of agriculture should be reemployed. This is because, while manufacturing is not necessarily the most efficient sector in the economy, it can be a growth accelerator and engine of inclusive growth for at least three reasons. First, manufacturers in emerging economies can benefit from manufacturing technologies developed in more advanced countries, and can achieve fast productivity growth. Second, manufacturing can absorb unskilled labor—thus providing improved employment opportunities for agricultural workers in low-income countries. Finally, manufacturers can export their products, so their growth will not be confined by limited domestic demand. Tradability is key, because high productivity growth can quickly lead producers to lower their prices and shed labor and capital if they cannot scale up their sales in bigger markets.

Is Industrialization a Broken Engine?

Virtually all successful emerging economies in the past 30 years have industrialized by leveraging this potential. Manufacturing offers opportunities to diversify away from agricultural and other traditional products, and helps the country pull itself out of poverty. But is this growth trajectory still feasible for today’s developing countries?

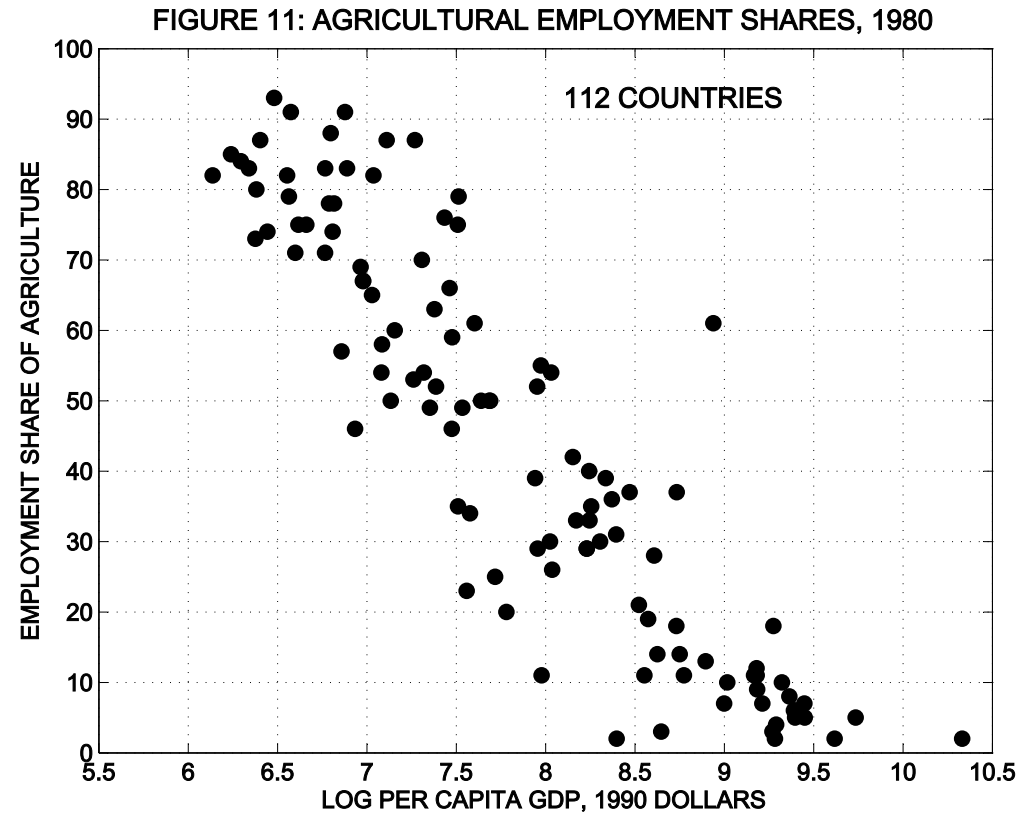

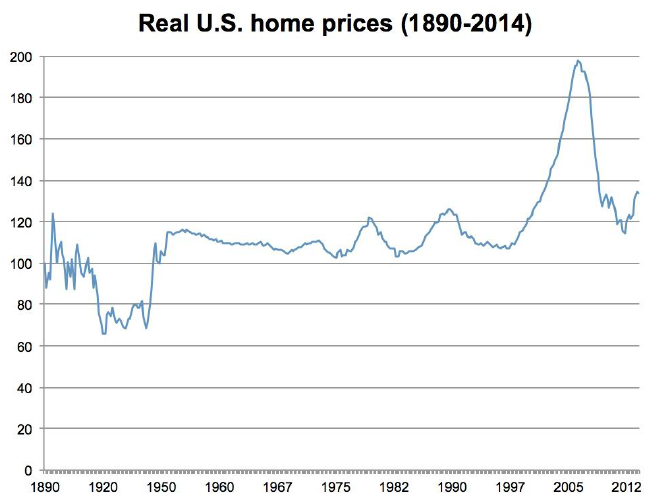

In most countries, the share of jobs and GDP arising from manufacturing expands in the early stages of development, then peaks and starts shrinking as relative prices decline and the economy matures. As Dani Rodrik and others have recently argued, latecomers to development in Africa and Latin America are hitting the peak earlier in the process, and are starting to deindustrialize when manufacturing has exploited only part of its potential. Ghani and O’Connell, for example, explore this inverted-U relationship between the level of economic development and the industry’s share of total employment, in a panel of 100 countries. They show how, in recent times, jobs in industry have grown more slowly and shrunk earlier in the development process (figure 2). The engine of industrialization seems to be running out of steam.

According to Rodrik, this manufacturing decline is mainly due to the adverse effects of trade and globalization on low- and middle-income countries in Africa and Latin America in two respects. First, these countries struggle in the international goods market because of a decline in the relative price of manufacturing in advanced economies, where technological progress has pushed up efficiency and reduced the need for expensive labor. Second, low transport costs and low trade barriers expose them to hyper-cheap production from East Asia, effectively reducing the scope for “import substitution” to expand the boost in manufacturing exports to the wider economy. This would suggest that today’s low-income countries will need to wait until East Asia becomes expensive before they industrialize.

A competing theory is that the low-income countries have subscribed to a trade system that is altogether unfavorable to them. On the one hand, to get access to international markets they are required to forgo protectionist policies that foster import substitution and screen nascent industries from foreign competition during their early development (see e.g., Ha-Joon Chang). On the other hand, trade barriers to advanced markets like the EU are set low for raw materials such as coffee beans and cocoa pods but high for the products obtained from processing of materials—in these examples, roasted coffee and chocolate. This means that the entry points to industrialization of commodity-dependent countries are essentially shut down.

Figure 2—Is Industrialization Running out of Steam?

Source: Ghani and O’Connell (2014) with World Bank data

Help Services

Both theories offer plausible explanations of why low-income countries struggle to industrialize. While more evidence on the causes of the problem is needed, it is increasingly clear that vast-scale industrialization has not featured in the development of most low-income countries. In contrast, the service sector has grown rapidly and absorbed lots of labor. Looking at Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, in the 15 years of this century . This pattern does not adequately represent how low-income countries grow and expand their productive capabilities, at least in that it does not capture the role of the variety and complexity of the products menu offered by these countries. Yet it can raise the question of how services can replace manufacturing as an engine of inclusive development. At least three routes can be identified.

First, there is a fringe of dynamic and tradable services that can boost the economy just as manufacturing does. Banking, customer services, and communications are examples of services which the ICT revolution has opened up to trade, and which can take low-income countries on a growth escalator, as the Indian boom has demonstrated. Crucially, investments in infrastructure, education, and human capital need to be made to facilitate development in these services. An alternative service attracting foreign demand with decent labor-absorption capacity is tourism.

Second, services are crucial inputs to manufacturing and there is evidence that their importance is growing. Hence cheap and efficient services such as transport and telecommunications can translate into stronger competitiveness of the tradable sector—both manufacturing and services.

Finally, the fact that manufacturing and services are becoming increasingly “blurred,” with services activities making up a higher share of manufacturing output, means that low-income countries could exploit a competitive edge on relevant service tasks. Moreover, these tasks can often be unbundled from merchandise production and traded along the global value chain. Logistics, marketing and post-sales services have been on the rise, not only in developed economies but also in developing ones. Furthermore, this trend could lead to a misinterpretation of statistics based on obsolete sector categories, effectively misleading our understanding of structural change.

In sum, the service sector offers new and interesting opportunities for growth, both through tradable services that plug directly into the global economy and through services that support competitiveness of manufacturing. In a global economy with fewer opportunities to industrialize, low-income countries will need to embed the service sector in their vision of inclusive growth and focus on the conditions that enable these opportunities.

Many thanks to my colleagues Joe Holden and Ignacio Fiestas for their helpful comments. This blog first appeared at: http://www.nathaninc.com/news/industrial-game-over-can-low-income-countries-grow-through-services-rather-industry

By

By  Lecture summary by

Lecture summary by