By Hugo Ferradans, current student in the Barcelona GSE Master in Economics of Public Policy. Follow him on Twitter @Hferradans.

In 2012, MIT professors Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson published one of the most compelling and resourceful books I have read in the field of development economics: Why Nations Fail. Their work suggests that the existence of extractive institutions and an extractive political class constraints to a large extent the ability of a country to experience prosperity and economic success.

Acemoglu and Robinson define extractive institutions as those institutions that create a system that moves resources from the many to a small powerful elite. In this sense, institutions that are extractive do not secure property rights to the population, nor provide an unbiased justice system that caters for the interests of the powerless. Many examples are given: North Korea vs. South Korea, Mexico vs. the United States, etc., drawing the conclusion that, if a society operates under the rule of a state that fails to create institutions that are democratic, a state will be bound to fail and not achieve a decent level of prosperity.

Although Acemoglu and Robinson’s work focuses on the relevance of extractive institutions in developing countries, this article will show how the argument could be easily expanded to developed countries like Spain.

Indeed, after many years of economic boom where money was flowing ferociously into the economy, Spain appears to have reached an economic and political cul-de-sac. Where did all the money go? How can it be that Spain is now leading the charts of extreme child poverty in the European Union, and at the same time is the country with the highest number of high-speed trains and empty houses in Europe?

At this point is where Why Nations Fail becomes appealing to me. I put forward the idea that Spain’s political class and institutions have behaved in an extractive manner and that this situation is largely due to a structural system of rent extraction, both at a institutional and cultural level, that drives the creation of wealth to the benefit of a few.

It is important to clarify, though, that this article appreciates that the extent to which Spain’s institutions are extractive is not the same as the ones described in Why Nations Fail. Spanish institutions do secure property rights and provide certain mechanisms to achieve a satisfactory level of development and economic growth. However, the construction and housing bubbles, as well as today’s economic policies put forward by the conservative party Partido Popular, suggest how many institutions are fuelling a system that perpetuates a ruling elite without trickling wealth down to the rest of the population.

I would like to introduce, not only at a political-economy-theory level, but also looking at a number of historical qualitative and quantitative data, how Acemoglu and Robinson’s discourse is crucial to understand today’s political and economic situation in Spain, and how a move towards a greater democratic and prosperous country will only be achieved by a regeneration of Spain’s political class.

Some history: from the 17th century until today

The creation of a very dense and static political and economic elite in Spain can be traced back to the 16th and 17th centuries. The combination between an absolutist government and a system of privileges that encouraged the middle class to abandon productive work and constitute tax-free property entails, created an elite (the so-called hidalguía) that was characterized by a rejection to culture and class mobility. Indeed, this elite was very supportive of the emergence of rent-seeking structures, as seen in the massive increase of mayorazgos during the decline of the Spanish empire, which ensured that the hidalguía could not see their capital reduced but only increased. In this way, even though Spain was being hit hardly by an economic turmoil at the beginning of the 17th century, the elite managed to keep their wealth at the expense of the whole population.

Such mechanisms of extraction from the population endured continuously over history, protecting the power of the government, the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie 1. It was not until the Second Republic (1930-1936) that Spain’s political elite was questioned. The Second Republic was a period in Spanish history where the government started to impose a number of very progressive and democratic policies, and where the cultural elites started to have a say in politics. Nevertheless, this ‘insurrection’ ended up being highly suppressed by a coup d’état from the military, obviously led by the previous political elite. This caused a Civil War that ultimately drove Spain into 40 years of a dictatorial regime under the rule of Francisco Franco, who brought back the previous system of corruption and rent-extraction to the country.

After Franco’s death, the transition to democracy was the result of a compromise between the old dictatorship heirs and a new class of younger politicians that had been organized in underground movements. Under these circumstances, the new democracy inherited many of the ways of doing politics that were customary of the Francoist regime. It is certainly not surprising, thus, that such an extended and static elitist system continued until today. In fact, the development of rent-seeking institutions that provided systems of extraction is something so ingrained in the Spanish society that it endured after the transition to democracy.

The construction and housing bubbles

This article puts forward the idea that one of the major exponents of such a system were the construction and housing bubbles. A huge expenditure in public infrastructure, both at the local and state levels, as well as a facilitation of housing construction by the local and regional governments has been a distinctive feature of Spanish politics over the last decades. Although many politicians have tried to argue that such a level of investment in public infrastructure was a way to provide the population with a system of “common welfare”, this political discourse seemed to confuse allocating public resources for construction of essential public transport systems, like fast-train lines and airports, with the supplying of unnecessary infrastructures in order to get private gain, such as, for example, Castellon’s airport, which has been opened since 2011 but has not managed to attract any flights yet.

Where institutions create culture: Spain’s ‘culture of ownership’

The Spanish housing market has been a case-study for many economists for showing some unusual features. One of the most prominent ones is the level of homeownerships when compared to the average European countries– 87% of Spanish population is living in owned rather than rented houses, in contrast with the 60% average of Europe. Many politicians have encouraged this market structure by stating that Spain has an innate ‘culture of ownership’ as opposed to other European countries, and thus Spaniards should follow this ‘Spanish way of life’. Nevertheless, this was not the case not that long ago. In fact, in 1950, 51% of the population lived under a rented property, and even in some cities such as Madrid and Barcelona this figure could increase up to 85%, indicating that this ‘Spanish way of life’ was more imposed by public institutions than ingrained in the DNA of the Spanish population, something that is consistent with Why Nations Fail’s argument that culture does not precede politics, but rather politics creates culture.

This change was fuelled by the minister of housing in 1957, José Luís Arrese, who, after stating the famous quote “Spain needs to be a country of owners, not of proletarians”, presented a political project to confront the increasing number of shacks in the metropolitan areas of cities. In this project, Arrese committed to undergo a series of reforms, such as a massive investment to build new houses and fiscal reforms to provide the majority of the population with their “right for adequate housing”. Although the number of social houses built during this period of time were almost nonexistent, many of the reforms that characterized the last decades of the Francoist regime marked a point of inflexion in the emergence of a ‘country of owners’ in Spain. In fact, housing started to be seen by the political elites as a mechanism of social control by which the revolutionary desires of the working classes could be brought down. Making the working classes subordinates not only to the state, but also to the national banks that provided them with credit, gave the regime a new sense in the ways they could control the population and undergo their political project. Expanding ownership and the housing sector would not only bring economic growth, but also political stability. This was clearly stated by Arrese, who mentioned in a speech in 1957:

“Man, when not given a proper shelter, tries to take over to the streets and, controlled by his bad mood, becomes subversive, bitter and violent.”

Nevertheless, the poor social housing provision and the systematic speculation that gave the elites notorious economic revenue produced an environment of total political disaffection and lack of credibility. In fact, many of the national companies that created this boom in housing during the 60s were extremely linked to the richest families in the country, some members of which were even part of the political and administrative elites as well.

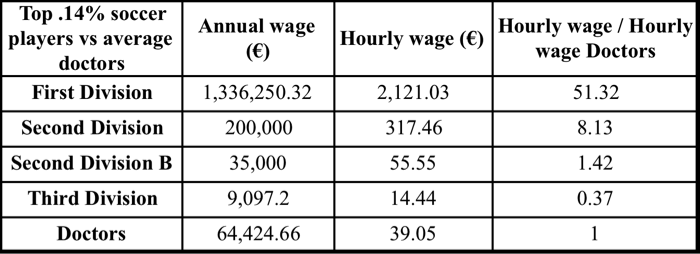

Furthermore, this desire to build a culture of homeownership further continued after the implementation of democracy, indicating again how housing was a mechanism of the elites to satisfy their interests. In 1985 and 1988, new reforms undertaken by the socialist government gave homeownership fiscal preference over renting. Buying a house could decrease by 15 to 17 percent the amount of income tax paid to the government. Also, Spain is the country with the lowest expenditure in social housing in Europe, spending 48.5 Euros per capita in contrast with the 117.06 of the European average. In this way, social housing did not expand in the years of the housing bubble because it ended up not being profitable for building companies. Thus, although the demand for social housing was increasing massively due to the systematic rise of housing prices in the real-estate market, the supply of social housing remained static, making it difficult for low-income families to buy a decent house.

The systematic fiscal compensations and the creation of a general belief by politicians that a house was ‘the best investment because prices never went down’ produced a general propensity for buying instead of renting. However, although the policies regarding tax discount for house ownership were massively applauded by the public, the real effects of these policies were neutral for consumers. The deduction of the tax for homeownership was actually compensated by the overpriced houses in the market, ultimately making the sellers, being big building companies and private banks, the only ones who benefited from this system of rent extraction. Furthermore, the political class was so linked to this culture of ownership and speculation that they would intensely benefit from the increase in prices and the rise in construction. In fact, many of the MPs in the national parliament owned more than three houses in 2011.

A political framework: the laws of urban planning

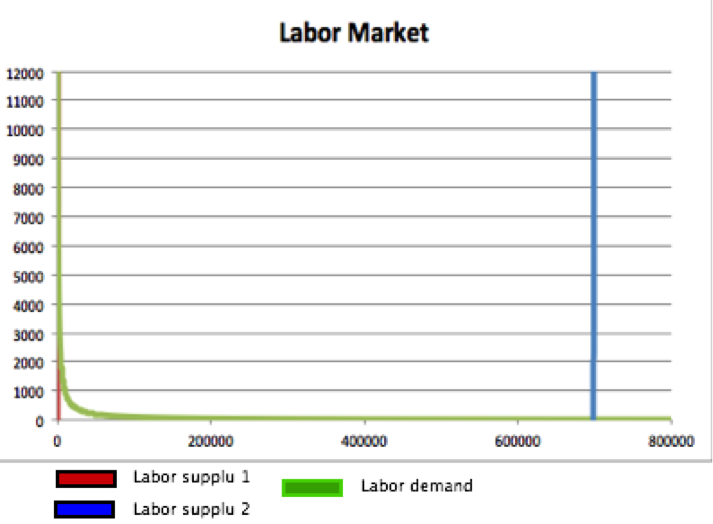

Besides the fuelling of a culture of ownership, Spain’s political class also created a framework in which speculation could operate freely, mainly taking the form of laws of urban planning that favoured mass construction.

In 1956, the Spanish government put forward the first law of urban development, which gave local councils the competencies to define whether an area was urban (suitable for building) or rural (unsuitable for building), as well as to determine the density of the construction to be taken place, making local governments able to redefine the land value of a specific area within a municipality.

However, this law was rather restrictive in some of the requirements for determining whether a piece of land is fit for urban development. To regulate and fuel the massive construction of houses during the housing bubble, successive governments put forward new laws that eased these requirements, such as the Law 7/1997 of 14th of April 1997 applied by José María Aznar, which allowed urban development in virtually any land throughout the country. In this way, local governments were able to easily increase the land value of particular unused areas by giving them an urban title. This fed the emergence of corruption during the housing boom years, since local governments could easily benefit the economic elites by increasing land values through giving land areas an urban title.

Furthermore, this new law gave local authorities the ability to issue building permits according to their local urban plan. In possession of a building permit, landowners were entitled to start with the building or urbanization project, having, however, the legal duty to give 10 percent to 15 percent of the total construction costs of the new urban development to the local authority. Both the state and landowners, thus, had very strong incentives to expand urban land, since local authorities could benefit financially from expanding areas of urbanisation and landowners could retain much of the value of their already valuable lands. Many municipalities were intensely financed by these forms of revenue, as seen in Valencia.

In addition, the decisions about the land title given to certain areas within a municipality tended to be signed by local authorities and private companies privately through the so-called convenios urbanísticos, which actually lacked any kind of transparency and regulation by the state. Politicians and private companies could negotiate many of the conditions for urban development in a city without a formal legal framework that regulated a possible case of interests in the negotiation of the convenio urbanístico.

It is important to differentiate how Spain’s legal framework is different from other similar developed countries in Europe. Indeed, many countries give councils the ability to decide the nature of lands in cities. Cities in France and Germany, for example, are also able to do so. In Spain, however, there is a system that gives private companies and local authorities incentives to expand urban land and build. Since local governments will get a big amount of revenue from giving building permits to private companies, they will deliberately do so to finance their debt. Also, since the negotiations between public and private actors were not regulated, local authorities and companies set urban policies to generate capital gains for the elites at the expense not only of creating a bubble in the economy, but also at the expense of environmental deterioration too.

The inefficient judicial system: a matter of resources?

Lastly, this article will briefly focus on Spain’s judicial system. On the basis of Acemoglu and Robinson’s (2013) theoretical framework, a state that is not providing a system that “prevents theft and fraud” would be “failing to secure property rights and justice” among the population, and thus becomes extractive. In this sense, if Spain is not promoting a system that is independent from other actors such as the political elites and that controls the evolution of extractive activities from any agent in the economy, especially from the ones in power, it will be contributing indirectly to the existence of this rent-seeking society.

The current judicial system in Spain is very inefficient. The average time that takes a trial to proceed with a resolution is one of the highest in Europe, sometimes taking 10 year to know the outcome. The media and many politicians have argued that this problem is due to the lack of resources given to the judicial institutions. However, Spain’s expenditure on justice is 50% higher than in France, and only 10% lower than Germany. Also, the number of judges per 100,000 inhabitants is similar to the one in France.

The problem, thus, must go beyond a simple analysis of the resources given to its institutions. One of the main problems, and it is indeed connected to the construction bubble, is the overlap of the political class and the judicial system. The two main parties, PSOE and PP, control the judges through the General Judicial Board (CGPJ), the major institution of Spain that promotes the independence of the judicial system from the parliament and the senate. In fact, although in 1980 a law that established that 12 of the members of the CGPJ were chosen by other judges was put forward, this law was derogated in 1985, giving the Parliament the power to choose all of the 20 members of the CGPJ. From this moment on, the CGPJ became a body used by the political class to rule for their own interests, where both political parties are constantly replacing the members of the chamber every time they come into power. It is not surprising, thus, that a study put forward by the World Economic Forum places Spain in the 60th position out of 133 in terms of the independence of the judicial system in front of the parliament, the senate and many private companies, being behind countries such as Namibia, Botswana and Gambia.

Regarding the cases of corruption that rose during the boom years, many of the trials about political scandals are still not resolved because of both the inefficiency of the judicial system and the poor dependence from the political parties that the system of justice has. One of the clearest examples is the Gürtel case, where the power of the political parties over the justice system was uncovered by the suspension of the judge Baltasar Garzón, the one that started its investigation. Indeed, when many front-line politicians from the government of Valencia and the Autonomous Community of Madrid started to be accused of bribery, money laundering and tax evasion in relation to the construction activities, a number of right-wing parties, of which some were involved with the politicians accused, put forward a lawsuit against him for causes unrelated to the Gürtel case.

After a long process of investigation, the CGPJ decided to move Baltasar Garzón aside the case and suspend him as a judge for 10 years. Currently the investigation is still ongoing. Most of the front-line politicians that were related in the case, such as Francisco Camps, were not found guilty.

The fact that the Spanish judicial system is failing to impose the rule of law to prevent theft and fraud is not a matter of opinion. Many studies have analysed the trust that the public has towards the judicial system, finding that it presents one of the lowest in Europe, being at the same level as Greece and Bulgaria. The effects that this can have on the evolution of further rent-seeking activities similar to the housing bubble are massive, since politicians know that being involve in corrupted activities will not be punished by law.

Challenging the establishment

This article has focused on the manifold ways in which Spain’s institutions have created a system of rent-extraction, with specific attention to the construction and housing bubbles. Although this issue calls for a more extensive and resourced analysis, I believe that Acemoglu and Robinson’s theoretical framework provides a good starting point.

This article has concluded that Spanish institutions are extractive for the following reasons. First, it was argued that Spain has been historically a country with a strong political elite that rules for the interest of the elites. Institutions constantly created a culture that perpetuated a system of rent extraction, as seen in the creation of the mayorazgos, as well as the ‘culture of ownership’ so acclaimed during the housing boom years. Second, institutions and major politicians not only promoted a certain culture that benefited them, but also a national administrative and political structure that fuelled the construction sector, and thus ultimately moving public resources into their hands. Finally, politicians also fuelled the creation of a non-independent judicial system that ensures that corruptive activities are generally not charged by law.

It is crucial that Spanish citizens challenge the establishment. Some moves from new political parties, such as Podemos, appear to be opening a door for this. Nevertheless, it is still not clear how the political scene will change in the following months. There is much to come, and hopefully Spain will realize about this vital challenges.

References

- Colau, Ada. Vidas Hipotecadas. Lectio, 2012.

- Drelichman, Mauricio. “All that glitters: Precious Metals, rent seeking and the decline of Spain.” European Review of Economic History 9(3), 313-336 (2005).

- Molinas, César. Qué Hacer Con España? Destino, 2013.

- Navarro, Vicenç. “El subdesarrollo social de España.” Público, October 22, 2009.

[1] For example, the mayorazgos were not abolished until the 19th centruy.