This research paper explores the Northern Sea Route (henceforth NSR), which is a shipping lane located along the Russian Arctic coast, and its predicted impacts on the relevant economies, especially Russia, in 2013, the time when the NSR was about to play an instrumental role in future shipping. This paper will also examine the economic implications.

Russia is one of the largest economies in the world by nominal value and even ranks among the top ten by purchasing power parity (CIA factbook). Nevertheless, it is still classified as a developing country.

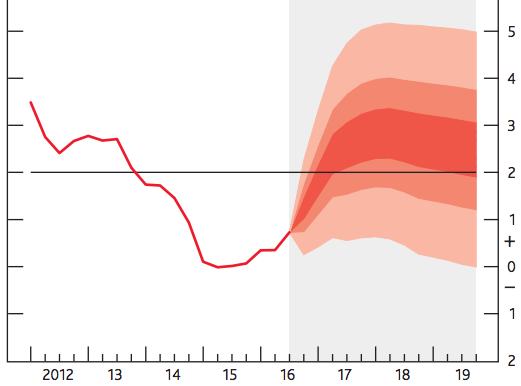

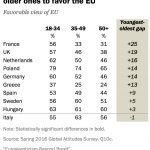

Figure 1: Russia’s GDP growth from 2010 to 2013 (Kolyandr and Ostroukh, 2013)

In 2012, Russia’s economic growth was solid, at a comfortable 3.4%, while the global economy was stuck in recession. The Russian rate of growth was faster than that of many other developing countries. Moreover, unemployment fell to 5.4%, which was a record low for the past 20 years. Not only that, wages grew considerably fast (see Figure 2). In 2013, Russia’s economy started to display signs of weakness. Its economic growth dropped to half the level of what it was in the decade leading up to the 2008 crisis, falling short of economists’ consistent expectation of a 1.9 percent rise. Some analysts and officials even started comparing the situation to a recession. In early 2013, the industrial output dropped for the first time since 2009. Furthermore, inflation increased in the second half of 2012 and was set to remain high in early 2013 (Kolyandr and Ostroukh, 2013).

Figure 2: Real wage growth in Russia in 2012 (trading economics)

One needs to adopt an international perspective when examining this case. The increase in inflation in Russia was related to three factors. First, overall inflation increase was due, in part, to the increase in food inflation triggered by the drought in Russia, exacerbated by a rise in prices among international grain producers, as well as higher consumption taxes on alcohol. Second, the rise in administrative prices in July and September 2012 and January 2013 led to inflated prices for services. Finally, there was an upward bend in core inflation, which excludes food and energy. After it had stabilized at approximately 5.7 percent for a few months, it increased from 5.1 percent in May 2012 to 5.8 percent in October 2012 (World Bank, 2013). Countries with high inflation face high government borrowing costs as a result, since lenders need to be compensated for the loss of their investments’ purchasing power. Low demand for industrial goods remained the main challenge for Russian businesses and, as a consequence, enterprises were not stimulated to invest and expand their production.

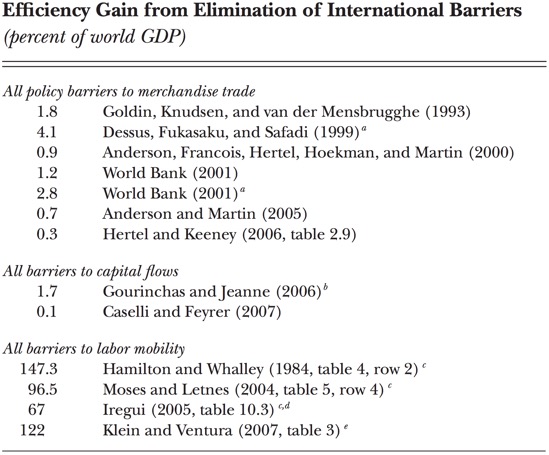

Russian official rates are known to have been high ever since the Perestroika. With an official interest rate of 8.25%, money and investment became very expensive relative to Russia’s main competitors. Banks would often ask for two-digit interest rates when lending. Consequently, this resulted in higher costs for loans and borrowed capital, thereby giving Russian stakeholders a competitive disadvantage when making investments. However, interest rates decreased from 15.2% in 2009 to 9.1% in 2012 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Interest rates for corporate loans on average (World Bank, 2013)

With regard to Russian shippers and ports, capital costs for investment decisions decreased by 40.13% on average. This certainly played in favor of the Russian shipping and port industry. On the other hand, other countries experienced a record low in interest rates. The EU, which harbors the competing ports as well as the most competitive shippers interested in the Northern Sea Route, will lend money at 0.5% through the European Central Bank. As a reference average lending rates to prime customers would therefore be at 3% (European Central Bank, 2013). Bearing these facts in mind, it is clear that pressure from finance-related costs had eased slightly. At the same time, however, competing companies from the EU would be able to acquire considerably cheaper capital than the companies located in or around St. Petersburg.

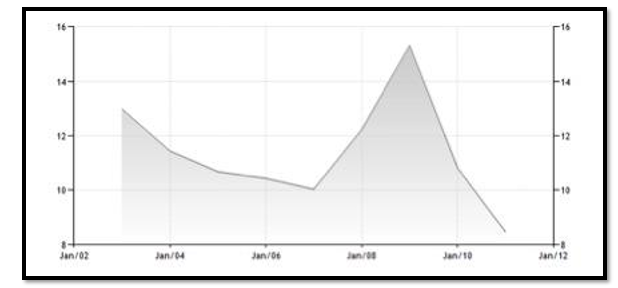

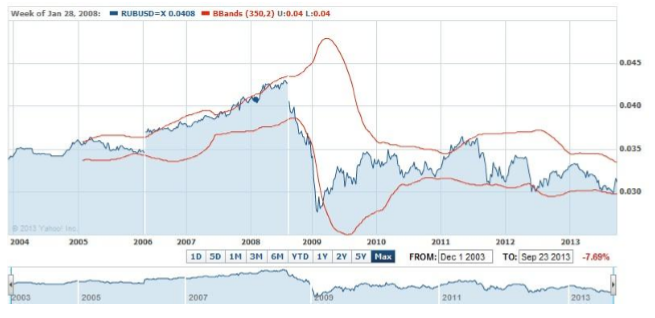

As shipping rates are almost exclusively quoted in European Euros and American Dollars, foreign exchange rates against those currencies played a major role in every internal and external calculation for shippers, ports and other stakeholders. In September 2013, 43-45 Russian Ruble could be exchanged for a Euro. Moreover, the Russian currency stood at around 32 RUB against one Dollar. However, the most important factor in foreign exchange related to long-term investment decisions (e.g. financing port infrastructure or new ships) as well as for daily money inflows (i.e. port handling fees, shipping revenue) is / was (present tense if it is a fact in general) volatility. The lower it is, the more predictable and, hence, the easier it becomes to calculate an investment decision for parties involved, i.e. the investor and the lender. Consequently, analyzing the Ruble’s performance and its volatility with Bollinger bands appears to be a suitable approach (Murphy, 1999).

As we see from Figure 4, volatility between the US Dollar and Russian Ruble clearly decreased compared to its trend at the beginning of the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009. However, volatility in this currency pair was still high enough to keep most American companies away from the Northeast Passage and its route. The volatility of the Ruble against the Euro was smaller. This was mainly due to steady, high volume of trade balance based on oil, gas and other raw materials, which offset the effects of an unstable Russian economy. Therefore, banks and especially forex finance were more optimistic about investments. For instance, they committed themselves to in- and outflows of the Russian Ruble.

Figure 4: Rates of US Dollar and Russian Ruble with Bollinger Bands (Yahoo Finance 2013)

To sum up, the NSR was meant to have a huge impact on the involved economies, especially Russia. But its neighboring countries, or countries otherwise depending on shipping, were likely to also be affected. Nevertheless, there will be more time needed to judge whether the predictions were correct.

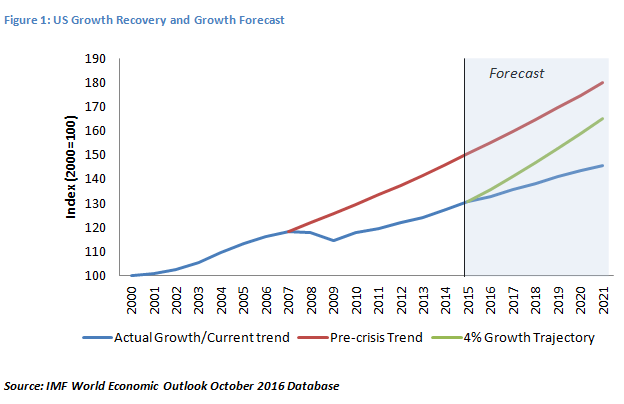

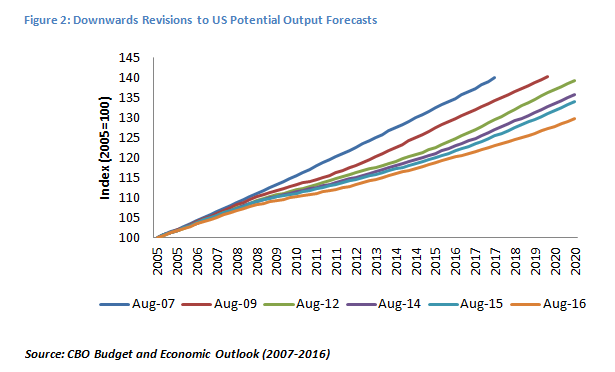

Editor’s note: In this post, Greg Ganics (Economics ’12 and PhD candidate at UPF-GPEFM) provides a non-technical summary of his job market paper, “Optimal density forecast combinations,” which has won the

Editor’s note: In this post, Greg Ganics (Economics ’12 and PhD candidate at UPF-GPEFM) provides a non-technical summary of his job market paper, “Optimal density forecast combinations,” which has won the