Post by Ana María Costa-Ramón ’14, Dimitria Gavalyugova ’14 and Ana Rodríguez-González ’14, alumni from the master’s in Economics at the Barcelona GSE

The gender gap is not unique. Or, at least, it is far from being a unidimensional concept. Rather, a vast literature demonstrates that it is multifaceted: we find gender gaps in education, the labor market, intrahousehold organization and politics, to say a few (Casarico and Profeta, 2015), and all of these are likely to be profoundly linked to one another. As Claudia Goldin points out, “these economic gender gaps have been a major issue in the women’s movement and a major issue for economists”. Here we mainly focus on just one of these dimensions – though complex enough: the gender pay gap.

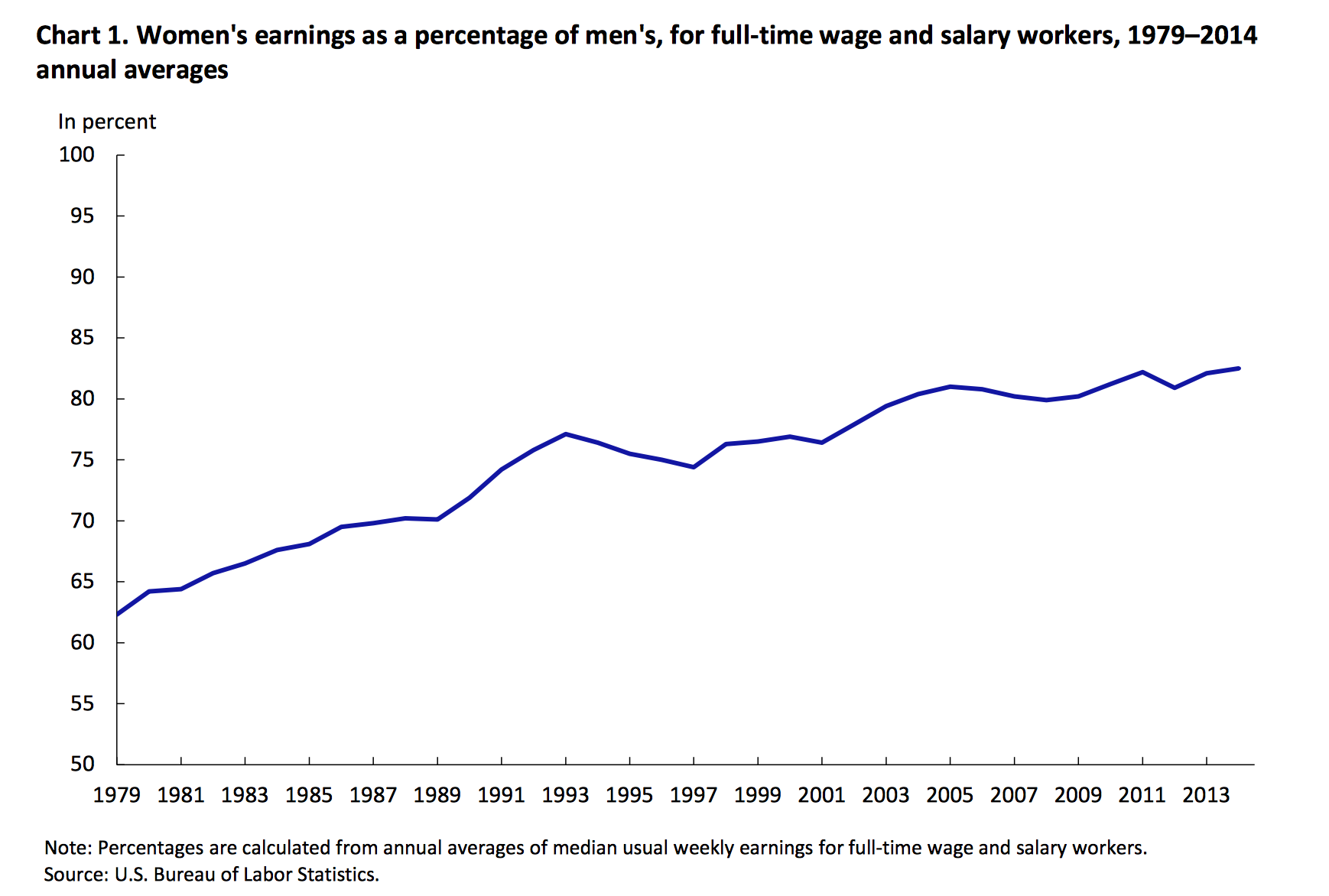

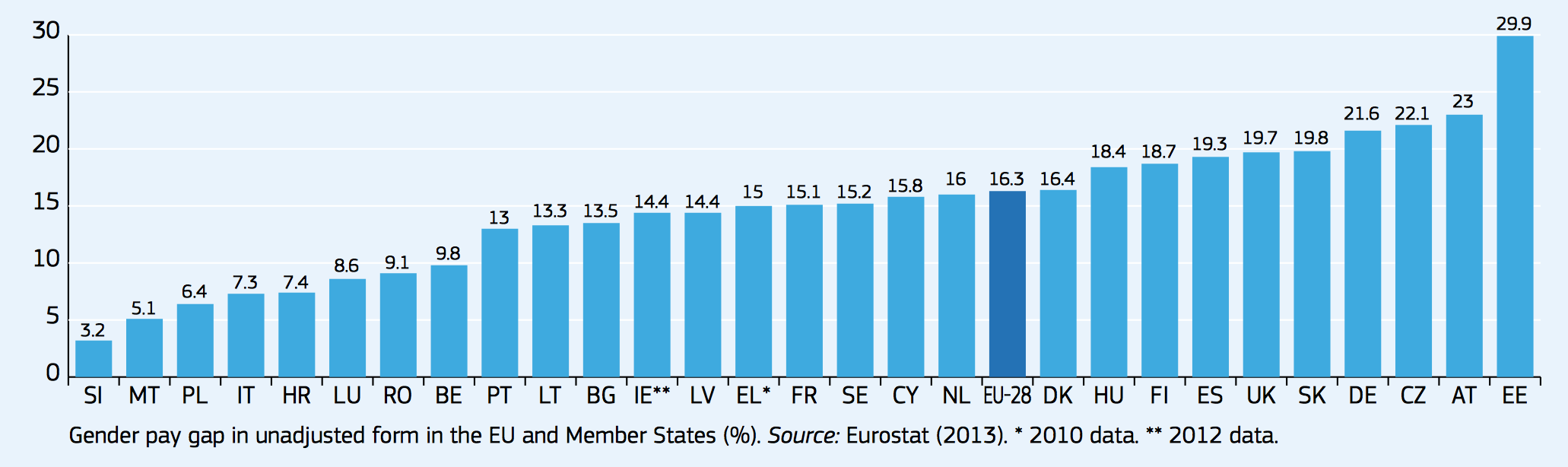

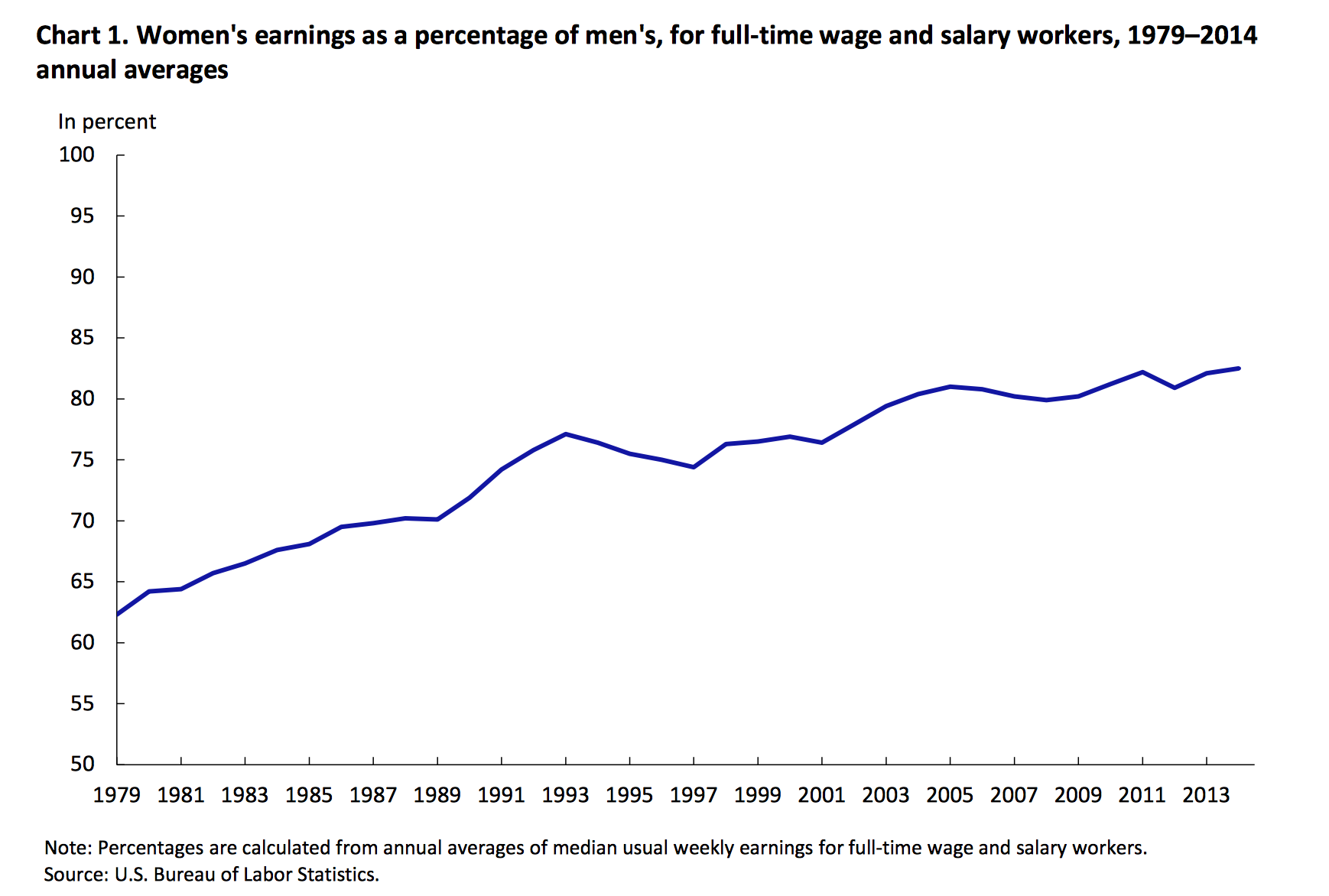

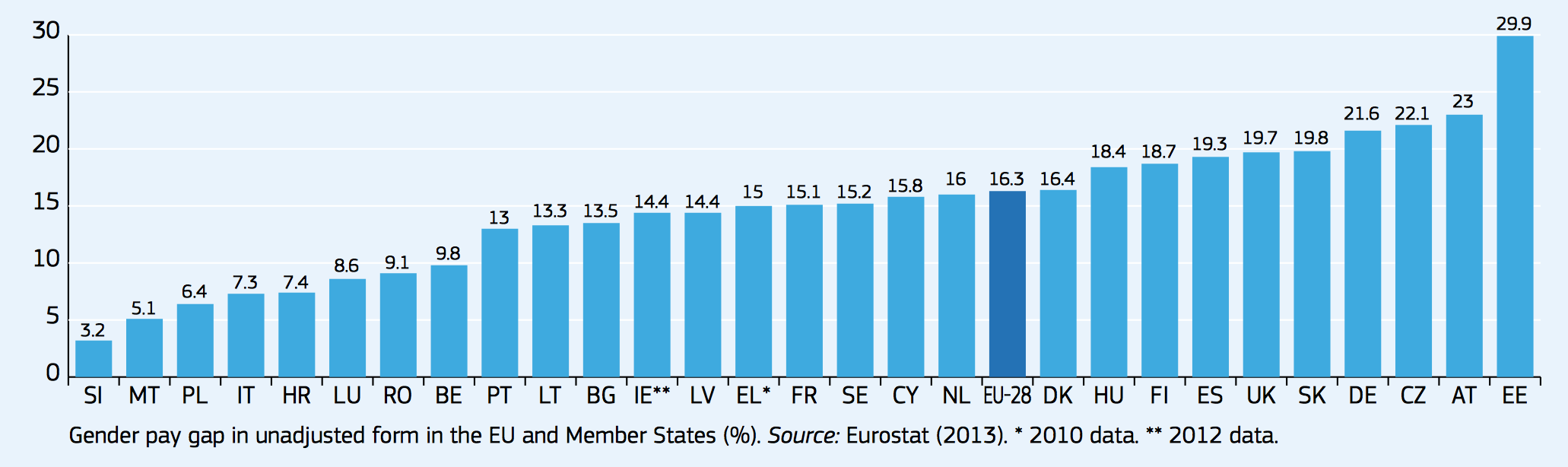

Although the gender-gap in earnings has decreased over time, it still remains firmly in place. For the US, in 2014, the gender-wage gap was 83%, meaning that women’s median earnings ($719) were 83% of those of male full-time wage and salary workers ($871). The picture for Europe is similar: in 2013 for the EU-28, the gender-pay gap defined in gross hourly earnings was 16.3%, meaning that women’s average earnings are 83.7% of male gross earnings.

Figure 1. Evolution of the gender pay gap in the US

Figure 2. The gender pay gap across European countries

In the late 90’s, human capital accumulation differences and sex-based discrimination were the main factors being discussed as potential causes of the gender gap in earnings. Although these explanations remain of first order relevance, in the last decade there has been an increasing interest in the analysis of gender-differences in psychological traits, social norms and preferences that has enriched this debate (Bertrand, 2011). In fact, together with direct discrimination and undervaluing of women’s work, labor market segregation and its subtle determinants have emerged as some of the most researched causes of the gender gap. In what follows, we will summarize some of the findings in this regard.

We could divide the recent literature that tries to explain labor market segregation into two main categories: those papers aimed at understanding the early determinants of the differential career choice by men and women (pre labor market entry) and those focusing on the later determinants – post labor market entry – which explain segregation from the labor market dynamics.

An important pre-labor market entry determinant of the gender-pay gap is the difference in education and career choices. Although many countries have taken significant steps towards achieving gender equality in education in recent decades, and girls outperform boys in most subjects, girls are still less likely than boys to be top performers in maths and to choose STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics] fields of study and, even when they do, they are less likely to take up careers in those fields (OECD, 2012). Among the main reasons suggested to explain this differential career choice are gender differences in some key psychological traits that are closely related; namely, competitiveness, risk aversion and overconfidence.

There is a large literature documenting gender differences in competitiveness. For example, Niederle and Vesterlund (2007) find in a lab experiment that women enter less than men into a competitive environment. Moreover, they document that the gender gap in competitiveness is not driven by performance and that, instead, gender differences in overconfidence and in taste for competition are more plausible explanations. In a later paper, these authors argue that the fact that women also perform worse than men under competition can explain part of the larger gap in mathematics performance at high percentiles of the distribution (Niederle and Vesterlund, 2010); that is, because the pressures associated with competition and risk-taking have a differential impact on boys and girls, the gender gap in math scores may not reflect only differences in skills, but also differences in responding to competitive environments. This is relevant, since math scores have been found to be a good predictor of future income and are associated with the track choice in tertiary education (Paglin and Rufolo, 1990). In fact, in a recent paper Buser et al (2014) link a experimental measure of competitiveness with the later choice of academic track and find that the gender difference in competitiveness can account for about 20% of the gender differences in track choice.

In the same line, it has also been well established that women are more risk averse than men (e.g. Booth et al., 2014; Charness and Gneezy, 2011). Risk aversion differences, as in the case of entry into competition, have also been hypothesized to have an effect on career choice and labor market segregation, as high-paying jobs may involve more risk-taking attitudes (Booth, 2009).

Similarly, several authors have also concluded that men are significantly more overconfident than women (e.g. Niederle and Vesterlund, 2007; Bengtsson et al, 2005). In fact, there is even some evidence that women are actually underconfident (Dahlbom et al, 2010; Jakobsson, 2012). These gender differences in overconfidence can also be an important factor contributing to the segregation of the labor market as they have been found to be associated with the willingness to start a new business (Koellinger et al, 2008), with risk-taking behavior in a financial context (Barber et al, 2001) or with competitiveness (Niederle et al, 2007), among others. In fact, Dahlbom et al (2010) argue that gender differences in confidence may perpetuate the segregated labor markets by means of self-selection.

Some authors have tried to explain what drives these gender differences in personality traits. This is an important question, because if these gender differences have, at least in part, a social origin and are influenced by stereotypes, then there is scope for policy intervention. In this line, Gneezy et al (2009) show that the finding that men are more competitive than women is not invariant to the social norms. They compare gender differences in self-selection into a competitive environment in a patriarchal society (Tanzania’s Maasai) versus in a matrilineal society (Northern India’s Khasi). While in the patriarchal society women self-select themselves into competition significantly less than their male counterparts, in the matrilineal society the proportions are reversed, and women actually appear more competitive than men. Booth and Nolen (2012; a, b) also point at socialization processes as potential drivers of the risk attitudes and willingness to compete of women. They study 15-year-old girls and find that their tendency to select themselves into competition and their risk aversion level is different for girls in single-sex schools than for girls in mixed-gender schools, with the former being more similar to the average boy in these aspects. D’Acunto (2015) conducts a lab experiment to measure the impact of gender identity on risk-taking behavior. He finds that making gender identity more salient increases risk taking for men. Finally, Iriberri and Rey-Biel (2011) find that making task stereotypes salient makes women underperform in a competitive setting.

The literature discussed above reveals that early gender differences in behavior, which have, at least in part, a social origin, can explain some of the difference in career choices made by males and females. However, one question remains: what sustains the gender pay gap within occupations? A number of works exist that shed light on certain institutional or job-related characteristics that can be held accountable.

Early literature focused on employers’ discriminatory promotion standards, founded on the higher probability of leaving for females (Lazear and Rosen,1990). Another phenomenon that has been of interest for earlier work is what has been dubbed as the “child-earning penalty” (e.g. Waldfogel,1998).

The latter mechanism has motivated a significant number of studies to explore the role of government-mandated parental leave as a potential remedy (Klerman and Leibowitz, 1997; Ruhm, 1998; Lalive and Zweimuller, 2009). While maternity leave policies have been found to yield mixed effects on females’ labor market attachment and earnings (Blau and Kahn, 2013), the effect of the introduction of paternity leave still remains to be explored in depth. As will become clear from the next paragraph, paternity leave policies, among others, may actually serve as a more effective instrument for bridging the gap between male and female earnings.

Present-day literature on occupational determinants of the pay gap is shifting its focus towards time-intensity and remuneration structures that affect females disproportionately. In particular, in her 2014 presidential address to the American Economic Association, Claudia Goldin put forth the hypothesis that it is convex (as opposed to linear) returns to inflexibility and long hours within high-paid (and predominantly competitive) occupations that lead to a gender divergence in earnings. This theory can explain the finding that the wage gap between males and females with similar backgrounds is much lower for women without children, who have a weaker preference for a flexible schedule. It also provides support for the thesis that lowering the cost of long-hours for females may help them benefit from these convex returns.

Some recent empirical studies have already emerged to back this theory. Wasserman (2015) provides some evidence of a tradeoff between family formation and high-paid more time-intensive specialties for female medical residents, while Cortés and Pan (2014) show that expanding women’s capacity to work longer hours can contribute to closing the gender pay gap.

Conclusion:

Although it is true that most Western societies have turned gender equality into a priority, differences in labor market outcomes for males and females persist, in part due to innate characteristics, prejudice and stereotypes and in part to labor market requirements. Closing what Goldin (2014) refers to as “the last chapter of gender convergence” thus involves addressing both the behavioral and the institutional channels behind the gender gap. As the OECD (2012) points out, aspirations are formed at a young age and thus, if we want to see gender-based wage disparities vanish, we should focus our attention on changing gender stereotypes and attitudes as early as possible. Further, mitigating the work-family trade-off experienced by women at a later stage in life should be an integral part of any effort to eliminate inequality within occupations. Working towards altering cultural norms and stereotypes, as well as creating incentives for adjusting labor conditions, may appear costly at first, but it is surely a profitable investment in gender-equality in the long term. Because closing the gender-pay gap is not a zero-sum game where one group of individuals gains at the expense of others. Rather, it is a step towards a more equitable society, which, without a doubt, would benefit us all.

Bibliography:

Barber, B. M. and Odean, T. (2001). “Boys Will be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 261–292.

Bengtsson, C., Persson, M., Willenhag, P. (2005) “Gender and overconfidence.” Economics Letters, Vol. 86, 199 – 203. Continue reading “Mind the (Gender) Gap”