Editor’s note: In this post, Federica Daniele (Economics ’13 and PhD candidate at UPF-GPEFM) shares a summary of her paper, “The Implications of Declining Firm-Level Uncertainty for Consumption Variety and Cities,” which has won the 2017 UniCredit & Universities Economics Job Market Best Paper Award. She also offers some advice to aspiring PhD students in the Barcelona GSE Master’s programs.

Paper summary

There is something alarming about the direction in which firm dynamics have been changing over the course of the last decades. Today it’s much rarer to encounter firms that undergo large up/downsizings than it used to be in the past: in other words, firms have become more tied to their rank in the firm size distribution. This has been of concern for many economists, who see this happening jointly with a slowdown in aggregate productivity growth and competitiveness. Being aware that the question on the drivers behind this trend and its consequences was still open to debate, coupled with an interest for entrepreneurship, is what pushed me to dive into this topic to better our understanding of the issue in my paper, “The Implications of Declining Firm-Level Uncertainty for Consumption Variety and Cities.”

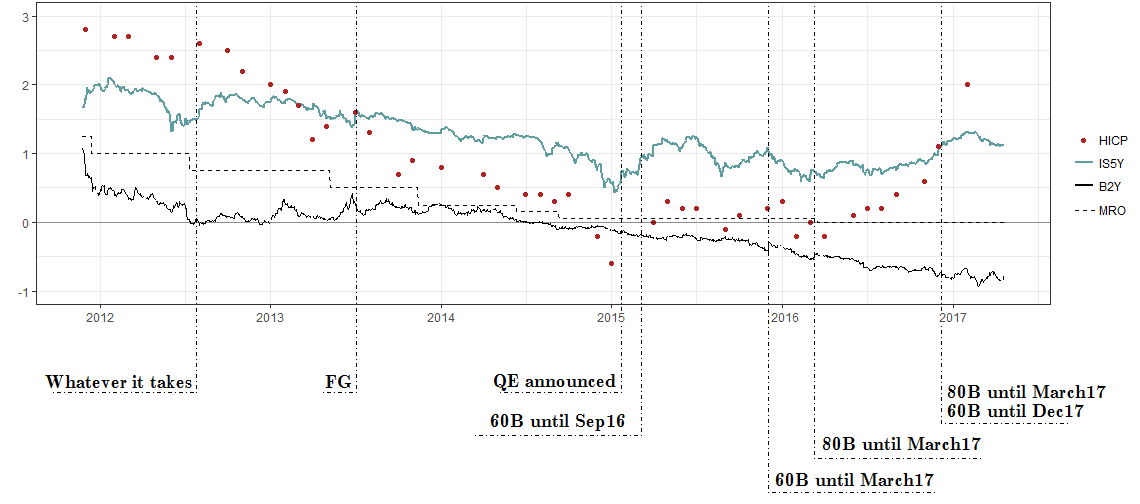

An explanation for the decline in business dynamism consistent with the data is that technological change has caused the degree of idiosyncratic uncertainty that firms routinely face about their chances to grow to go down. This implies that today most of the return from starting a firm is determined by its initial (in)success as opposed to luck in the development of the business over its life-cycle. Based on evidence drawn from data on the universe of German establishments, in the paper I argue that a reduction in firm-level uncertainty is consistent with lower incentives for potential entrepreneurs to start a new business. My paper offers a new insight into the literature on the role of uncertainty for economic activity: some degree of uncertainty is beneficial, because – by unlocking the opportunity for a given firm to grow large out of fortuitous events (such as a favourable demand turn) – it encourages entrepreneurship. In this sense, my paper provides a defence of the classical argument by Frank Knight according to which risk-taking is a characterising feature of entrepreneurship.

A deficit in the growth rate of the stock of establishments triggered by a decline in firm-level uncertainty is cause of concern for multiple reasons. In my paper, I investigate the importance of two dimensions: first of all, the fact that consumers get to consume a less wide variety of goods than otherwise; and secondly, the fact that, being the loss in entrepreneurship larger in big cities, fewer consumers find appealing to move to large cities than otherwise, thus diminishing the extent of positive spillovers due to higher urban density. Another outcome of interest would have been, for example, the process of innovation within an industry.

All in all, the contribution of this paper consists of assessing both empirically and theoretically novel long-run consequences on economic activity of declining firm-level uncertainty.

Advice for future PhD students

I think Barcelona GSE masters students who are considering going the PhD / academic career route should be strategic. There is no harm in taking one year to do some exploratory work, working as RA, for example, for some good professor, if that buys the time to figure out what kind of research best matches your interests, in which institution you would feel better fulfilled, or whether academia suits you at all.

In the end, if you choose to pursue the academic route, you will have most certainly achieved a better match with the institution/supervisor, and spared a lot of time later on during the course of the PhD, which you can instead dedicate to producing research of good quality.

But even if you decide that academia is not for you, the value of the investment will still be positive, as experimenting early during one’s working career is much less costly than doing it later.