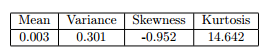

By Cox Bogaards, Marceline Noumoe Feze, Swasti Gupta, Mia Kim Veloso

Almost a year since the UK voted to leave the EU, uncertainty still remains elevated with the UK’s Economic Policy Index at historical highs. With Theresa May’s snap General Election in just under two weeks, the Labour party has narrowed the gap from Conservative lead to five percentage points, which combined with weak GDP data of only 0.2 per cent growth in Q1 2017 released yesterday, has driven the pound sterling to a three-week low against the dollar. Given potentially large repurcussions of market sentiment and financial market volatility on the economy as a whole, this series of events has further emphasised the the need for policymakers to implement effective forecasting models.

In this analysis, we contribute to ongoing research by assessing whether the uncertainty in the aftermath of the UK’s vote to leave the EU could have been predicted. Using the volatility of the Pound-Euro exchange rate as a measure of risk and uncertainty, we test the performance of one-step ahead forecast models including ARCH, GARCH and rolling variance in explaining the uncertainty that ensued in the aftermath of the Brexit vote.

Introduction

The UK’s referendum on EU membership is a prime example of an event which perpetuated financial market volatility and wider uncertainty. On 20th February 2016, UK Prime Minister David Cameron announced the official referendum date on whether Britain should remain in the EU, and it was largely seen as one of the biggest political decisions made by the British government in decades.

Assessment by HM Treasury (2016) on the immediate impacts suggested “a vote to leave would cause an immediate and profound economic shock creating instability and uncertainty”, and in a severe shock scenario could see sterling effective exchange rate index depreciate by as much as 15 percent. This was echoed in responses to the Centre for Macroeconomics’ (CFM) survey (25th February 2016), where 93 percent of respondents agreed that the possibility of the UK leaving the EU would lead to increased volatility in financial markets and the broader economy, expressing uncertainty about the post-Brexit world.

Resonating these views, the UK’s vote to leave the EU on 23rd June 2016 indeed led to significant currency impacts including GBP devaluation and greater volatility. On 27th June 2016, the Pound Sterling fell to $1.315, reaching a 31-year low against the dollar since 1985 and below the value of the Pound’s “Black Wednesday” value in 1992 when the UK left the ERM.

In this analysis, we assess whether the uncertainty in the aftermath of the UK’s vote to leave the EU could have been predicted. Using the volatility of Pound-Euro exchange rate as a measure of risk and uncertainty, we test the performance of one-step ahead forecast models including ARCH, GARCH and rolling variance. We conduct an out-of-sample forecast based on models using daily data pre-announcement (from 1st January 2010 until 19th February 2016) and test performance against the actual data from 22nd February 2016 to 28th February 2017.

Descriptive Statistics and Dynamic Properties

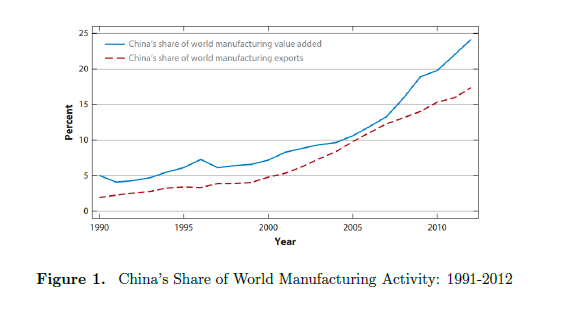

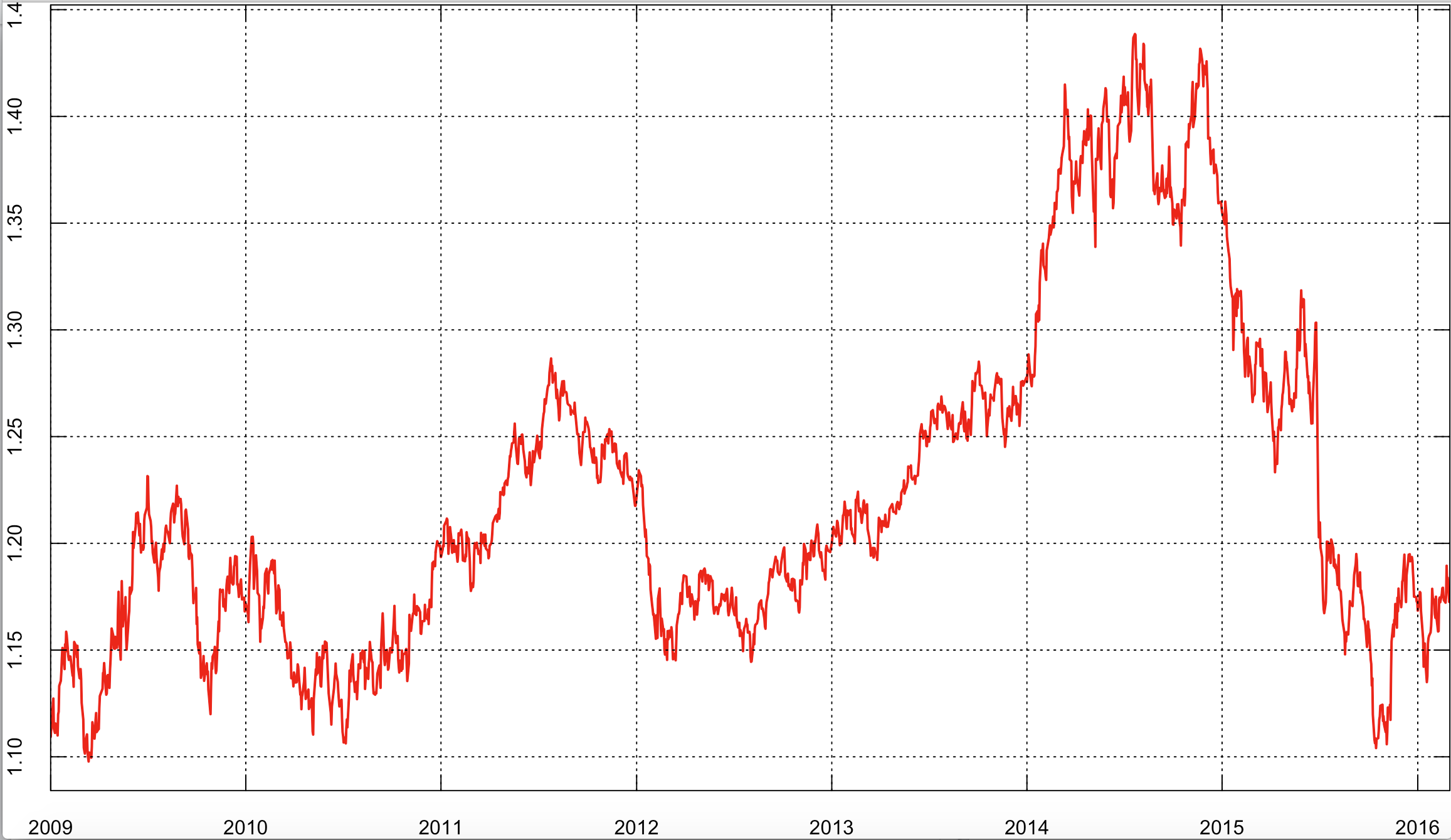

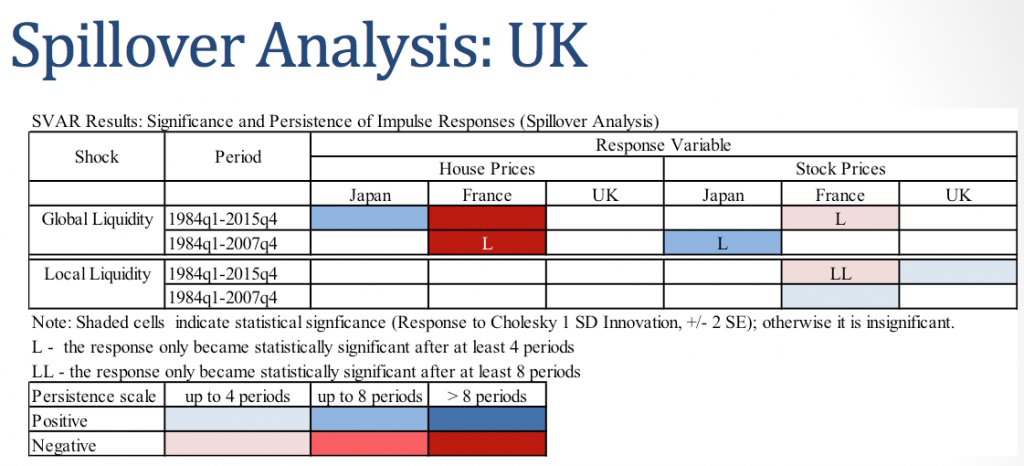

As can be seen in Figure 1, the value of the Pound exhibits a general upward trend against the Euro over the majority of our sample. The series peaks at the start of 2016, and begins a sharp downtrend afterwards. There are several noticeable movements in the exchange rate, which can be traced back to key events, and we can also comment on the volatility of exchange rate returns surrounding these events, as a proxy for the level of uncertainty, shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1: GBP/EUR Exchange Rate

Source: Sveriges Riksbank and authors’ calculations

Notably, over our sample, the pound reached its lowest level against the Euro at €1.10 in March 2010, amid pressure from the European Commission on the UK government to cut spending, along with a bearish housing market in England and Wales. The Pound was still recovering from the recent financial crisis in which it was severely affected during which it almost reached parity with the Euro at €1.02 in December 2008 – its lowest recorded value since the Euro’s inception (Kollewe 2008).

However, from the second half of 2011 the Pound began rising against the Euro, as the Eurozone debt crisis began to unfold. After some fears over a new recession due to consistently weak industrial output, by July 2015 the pound hit a seven and a half year high against the Euro at 1.44. Volatility over this period remained relatively low, except in the run up to the UK General elections in early 2015.

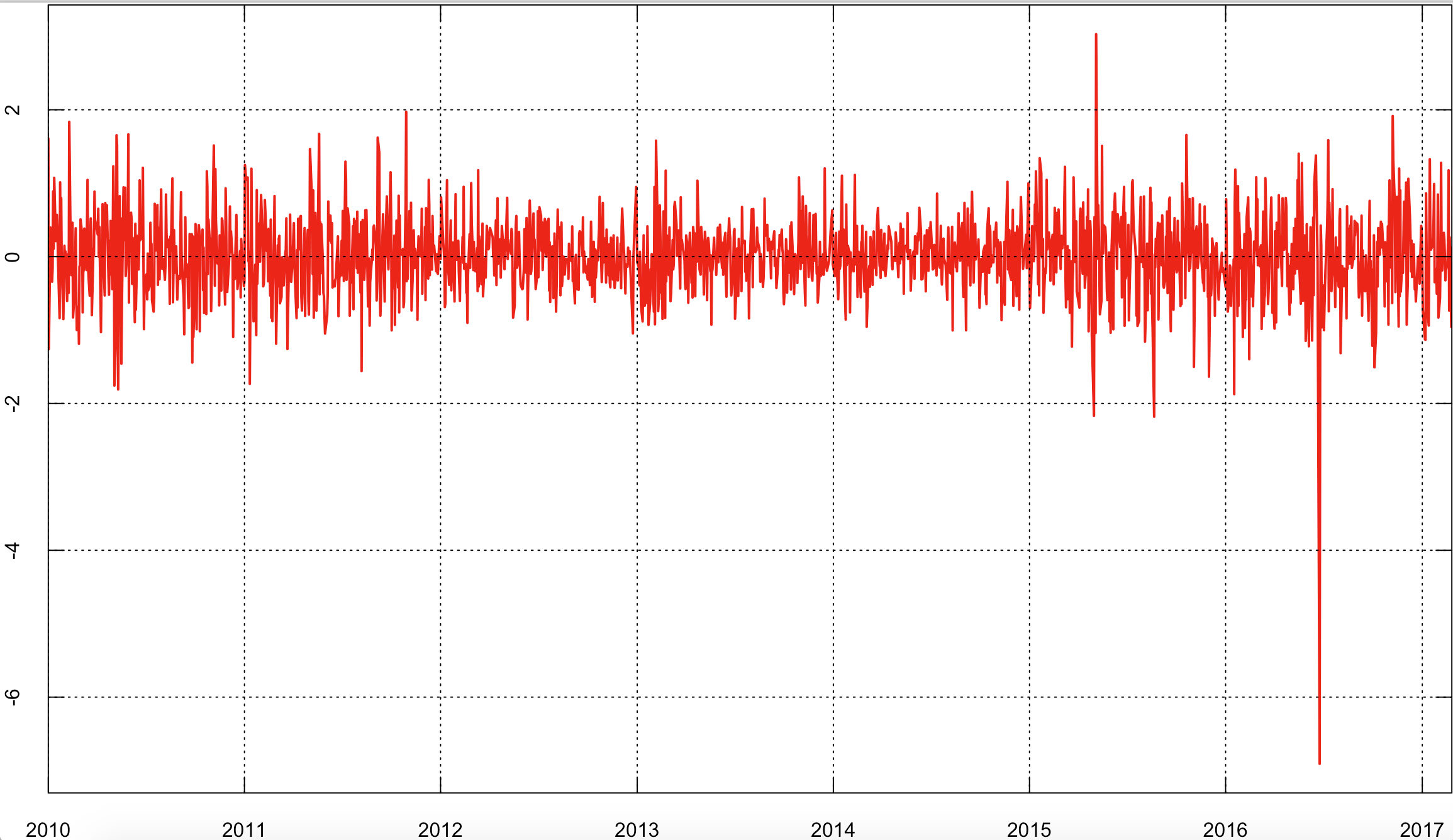

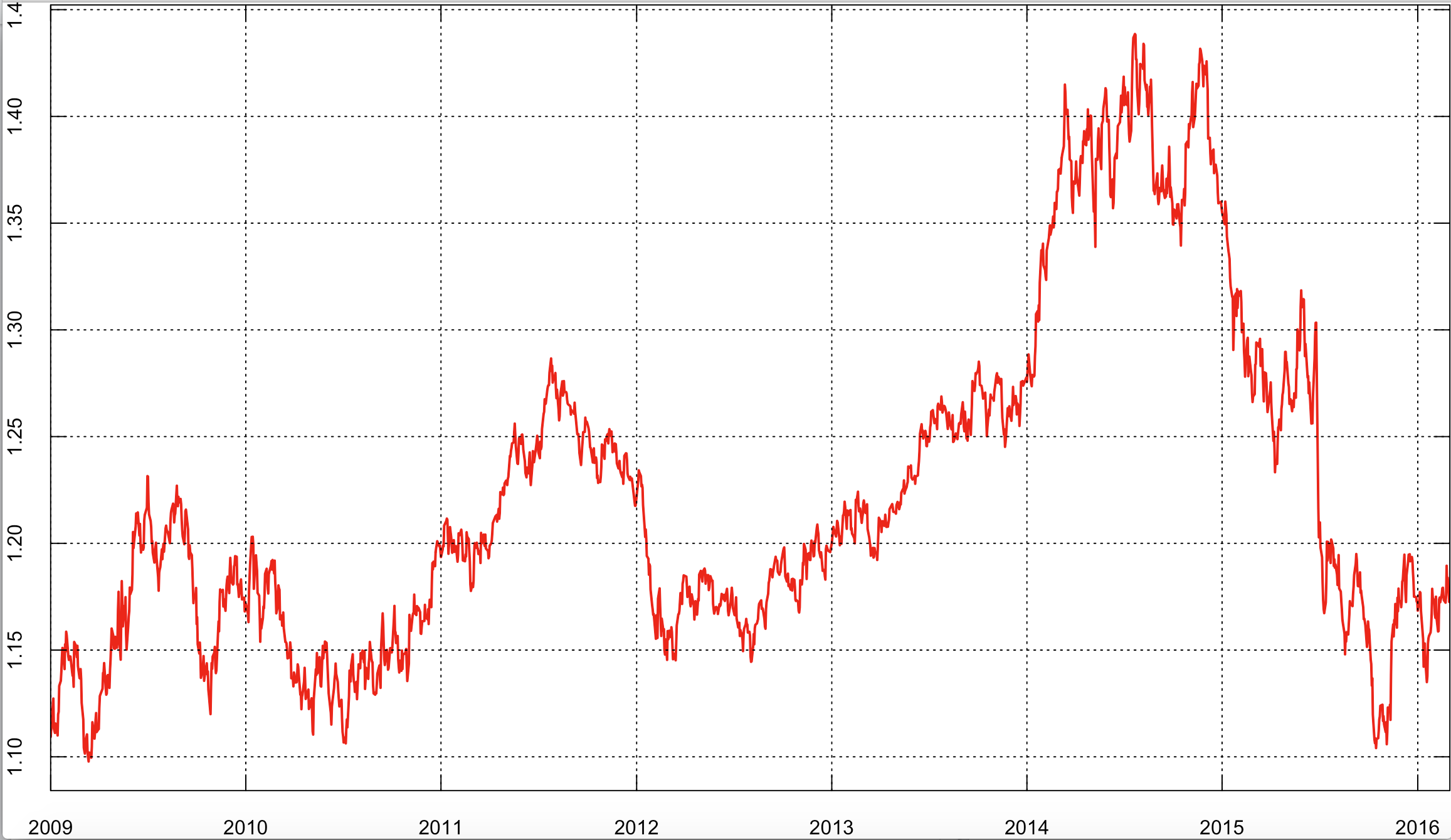

However, Britain’s vote to leave the EU on 23rd June 2016 raised investors’ concerns about the economic prospects of the UK. In the next 24 hours, the Pound depreciated by 1.5 per cent on the immediate news of the exit vote and by a further 5.5 per cent over the weekend that followed, causing volatility to spike to new record levels as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Volatility of GBP/EUR Exchange Rate

Source: Sveriges Riksbank and authors’ calculations

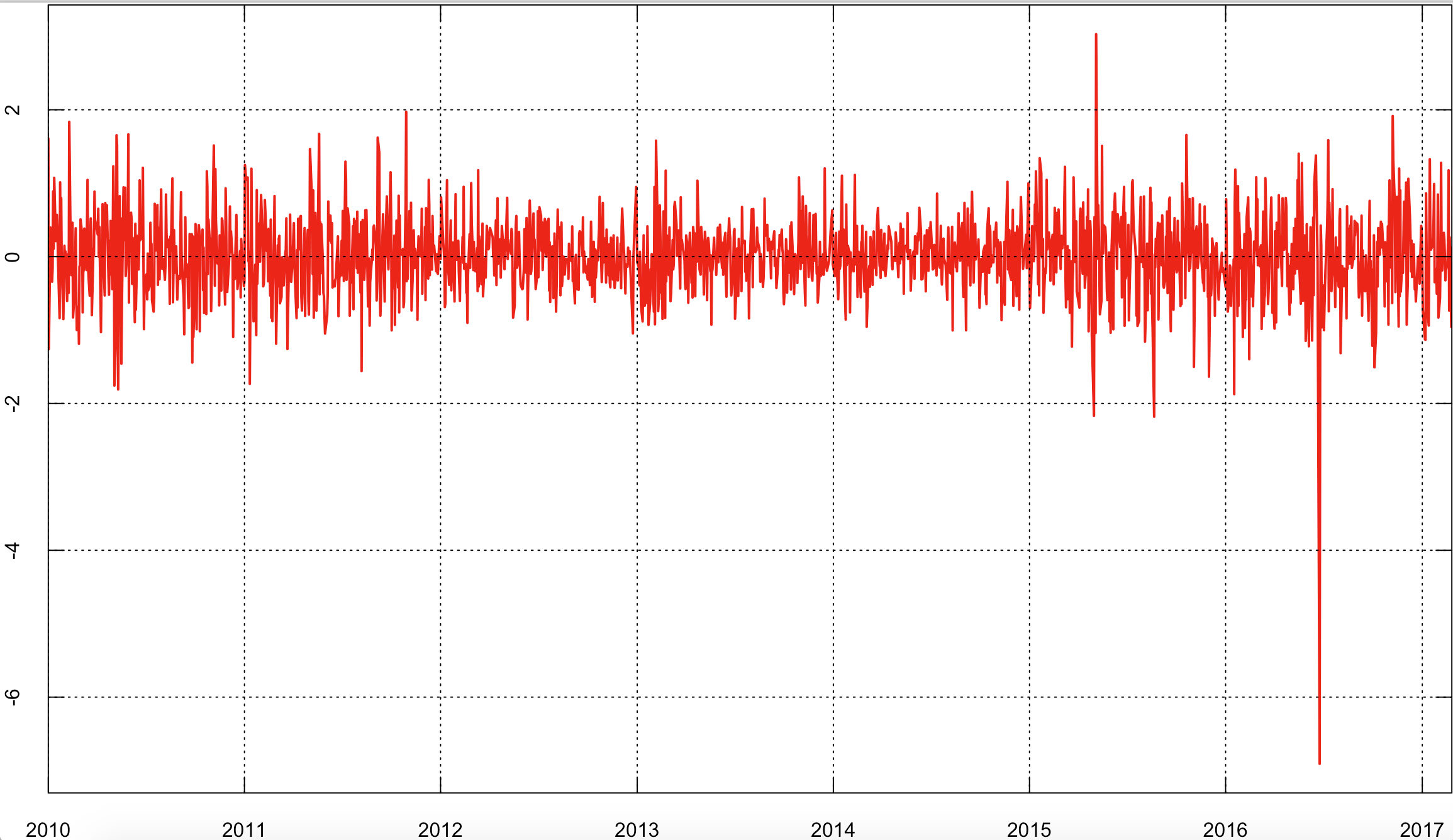

As seen in Figure 1, the GBP-EUR exchange rate series is trending for majority of the sample, and this may reflect non-stationarity in which case standard asymptotic theory would be violated, resulting in infinitely persistent shocks. We conduct an Augmented Dickey Fuller test on the exchange rate and find evidence of non-stationarity, and proceed by creating daily log returns in order to de-trend the series. Table 1 summarises the first four moments of the log daily returns series, which is stationary.

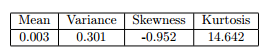

Table 1: Summary Statistics

Source: Sveriges Riksbank and authors’ calculations

The series has a mean close to zero, suggesting that on average the Pound neither appreciates or depreciates against the Euro on a daily basis. There is a slight negative skew and significant kurtosis – almost five times higher than that of the normal distribution of three – as depicted in the kernel density plot below. This suggests that the distribution of daily returns for the GBP-EUR, like many financial time series, exhibits fat tails, i.e. it exhibits a higher probability of extreme changes than the normal distribution, as would be expected.

To determine whether there is any dependence in our series, we assess the autocorrelation in the returns. Carrying out a Ljung-Box test using 22 lags, as this corresponds to a month of daily data, we cannot reject the null of no autocorrelation in the returns series, which is confirmed by an inspection of the autocorrelograms. While we find no evidence of dependence in the returns series, we find strong autocorrelations in the absolute and squared returns.

The non-significant ACF and PACF of returns, but significant ACFs of absolute and squared returns indicate that the series exhibits ARCH effects. This suggests that the variance of returns is changing over time, and there may be volatility clustering. To test this, we conduct an ARCH-LM test using four lag returns and find that the F-statistic is significant at the 0.05 level.

Estimation

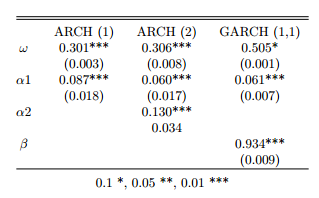

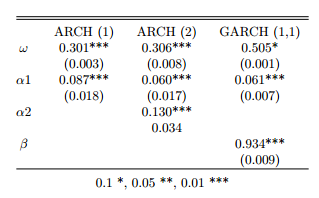

For the in-sample analysis we proceed using the Box-Jenkins methodology. Given the evidence of ARCH effects and volatility clustering using an ARCH-LM test but lack of any leverage effects in line with economic theory, we proceed to estimate models which can capture this: ARCH (1), ARCH (2), and the GARCH (1,1). Estimation of ARCH (1) suggests low persistence as captured by α1 and relatively fast mean reversion. The ARCH(2) model generates greater persistence measured by sum of α1 and α2 and but still not as large as the GARCH(1,1) model, sum of α1 and β as shown in table 2.

Table 2: Parameter Estimates

We proceed to forecast using the ARCH(1) as it has the lowest AIC and BIC in-sample, and GARCH (1,1) which has the most normally distributed residuals, no dependence in absolute levels, and the largest log-likelihood. We compare performance against a baseline 5 day rolling variance model.

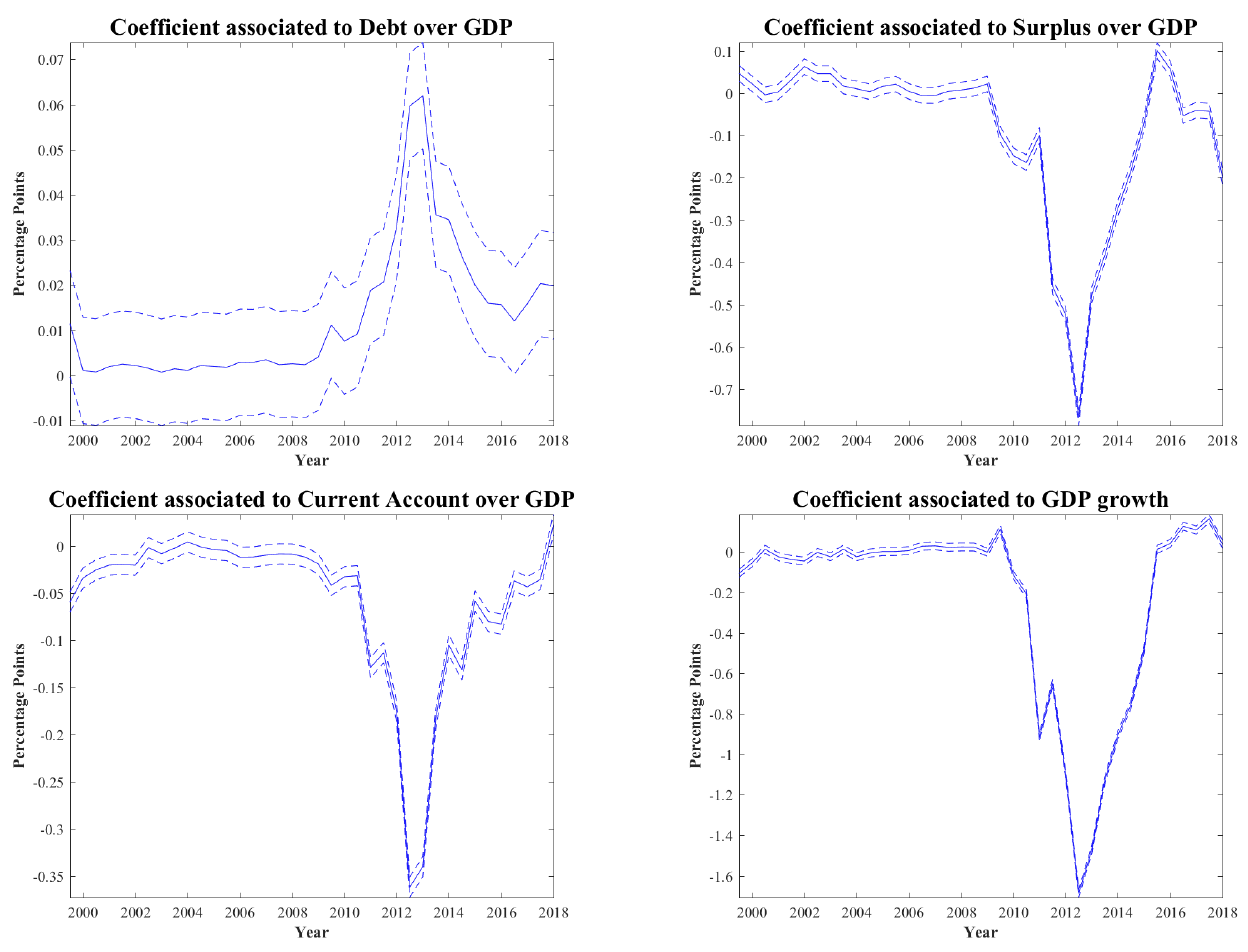

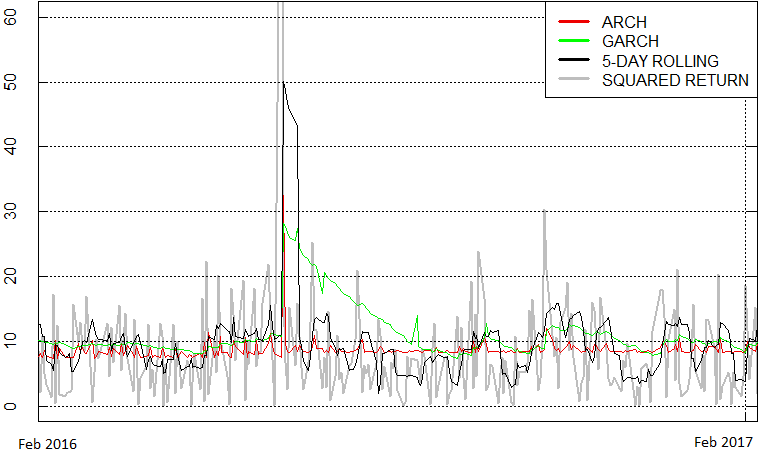

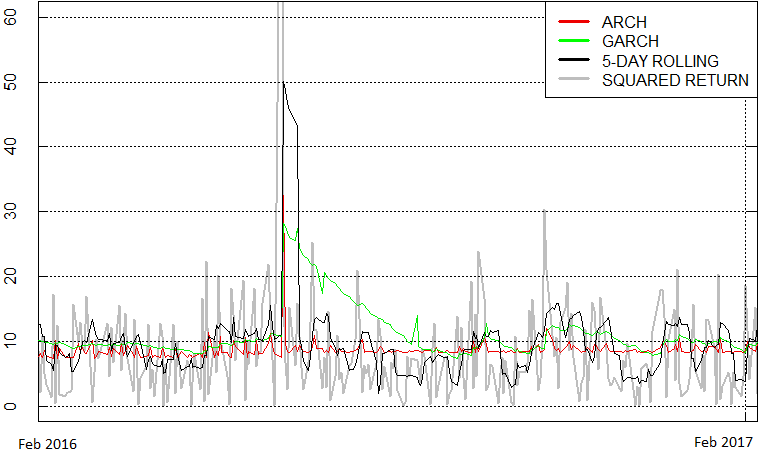

Figure 3 plots the out of sample forecasts of the three models (from 22nd February 2016 to 28th February 2017). The ARCH model is able to capture the spike in volatility surrounding the referendum, however the shock does not persist. In contrast, the effect of this shock in the GARCH model fades more slowly suggesting that uncertainty persists for a longer time. However neither of the models fully capture the magnitude of the spike in volatility. This is in line with Dukich et al’s (2010) and Miletic’s (2014) findings that GARCH models are not able to adequately capture the sudden shifts in volatility associated with shocks.

Figure 3: Volatility forecasts and Squared Returns (5-day Rolling window)

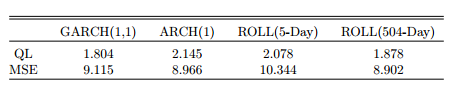

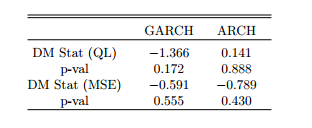

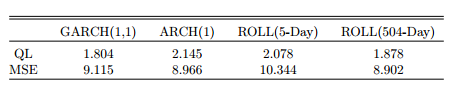

We use two losses traditionally used in the volatility forecasting literature namely the quasi-likelihood (QL) loss and the mean-squared error (MSE) loss. QL depends only on the multiplicative forecast error, whereas the MSE depends only on the additive forecast error. Among the two losses, QL is often more recommended as MSE has a bias that is proportional to the square of the true variance, while the bias of QL is independent of the volatility level. As shown in table 3, GARCH(1,1) has the lowest QL, while the ARCH (1) and rolling variance perform better on the MSE measure.

Table 3: QL & MSE

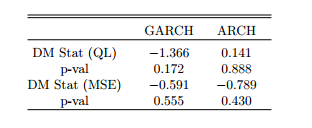

Table 4: Diebold- Mariano Test (w/5-day Rolling window)

Employing the Diebold-Mariano (DM) Test, we find that there is no significance in the DM statistics of both the QL and MSE. Neither the GARCH nor ARCH are found to perform significantly better than the 5-day Rolling Variance.

Conclusion

In this analysis, we tested various models to forecast the volatility of the Pound exchange rate against the Euro in light of the Brexit referendum. In line with Miletić (2014), we find that despite accounting for volatility clustering through ARCH effects, our models do not fully capture volatility during periods of extremely high uncertainty.

We find that the shock to the exchange rate resulted in a large but temporary swing in volatility but this did not persist as long as predicted by the GARCH model. In contrast, the ARCH model has a very low persistence, and while it captures the temporary spike in volatility well, it quickly reverts to the unconditional mean. To the extent that we can consider exchange rate volatility as a measure of risk and uncertainty, we may have expected the outcome of Brexit to have a long term effect on uncertainty. However, we observe that the exchange rate volatility after Brexit does not seem significantly higher than before. This may suggest that either uncertainty does not persist (unlikely) or that the Pound-Euro exchange rate volatility does not capture fully the uncertainty surrounding the future of the UK outside the EU.

References

Abdalla S.Z.S (2012), “Modelling Exchange Rate Volatility using GARCH Models: Empirical Evidence from Arab Countries”, International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(3), 216-229

Allen K.and Monaghan A. “Brexit Fallout – the Economic Impact in Six Key Charts.” www.theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media Limited, 8 Jul. 2016. Web. Accessed: March 11, 2017

Brownlees C., Engle R., and Kelly B. (2011), “A Practical Guide to Volatility Forecasting Through Calm and Storm”, The Journal of Risk, 14(2), 3-22.

Centre for Macroeconomics (2016), “Brexit and Financial Market Volatility”. Accessed: March 9, 2017.

Cox, J. (2017) “Pound sterling falls after Labour slashes Tory lead in latest election poll”, independent.co.uk. Web. Accessed May 26, 2017

Diebold F. X. (2013), “Comparing Predictive Accuracy, Twenty Years Later: A Personal Perspective on the Use and Abuse of Diebold-Mariano Tests”. Dukich J., Kim K.Y., and Lin H.H. (2010), “Modeling Exchange Rates using the GARCH Model”

HM Treasury (2016), “HM Treasury analysis: the immediate economic impact of leaving the EU”, published 23rd May 2016.

Sveriges Riksbank, “Cross Rates” www.riksbank.se. Web. Accessed 16 Feb 2017

Taylor, A. and Taylor, M. (2004), “The Purchasing Power Parity Debate”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(4), 135-158.

Van Dijk, D., and Franses P.H. (2003), “Selecting a Nonlinear Time Series Model Using Weighted Tests of Equal Forecast Accuracy”, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 65, 727–44.

Tani, S. (2017), “Asian companies muddle through Brexit uncertainty” asia.nikkei.com. Web. Accessed: May 26, 2017