Written by: Fernando Fernandez and Mario Giarda

photo credit: Reuters

Some weeks ago, The Economist published an article about the state of the pension system in Chile. The article focused on the discontent that the system has generated since it was implemented back in 1981, under the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

Since its conception, the current Chilean pension system was built on two values: long-run sustainability and individual responsibility. These characteristics should be the building blocks of any pension system, and we think that most people would agree with them. Nowadays, the discontent comes from the low pensions this system is delivering, and the disproportionately high commission/fees charged by pension managers. In our view, given the current parameters of the system (retirement age, monthly individual contributions, return on funds), pensions would be hardly increased without incurring in higher public costs or higher individual effort. So, any scheme (individual accounts, pay-as-you-go, etc.) would face serious challenges in delivering acceptable pensions.

In what follows, we briefly describe the history of the system and analyze its current state. Then we discuss the main issues of recent debates. We argue that the first policy action is to change the parameters the system is working with. Finally, we discuss that the best pension system should be a mixed system based on two pillars: individual contributions and a solidarity pillar, the former financed with individual accounts and the latter funded by the State. This is exactly the current Chile’s pension system. In this piece, we aim to defend it and propose some policies to enhance its performance given the current state of the Chilean economy. Moreover, this article would be helpful to analyze other pension systems that are being stressed by the same developments taking place in Chile, like most European economies and countries have adopted similar systems like Peru.

A brief history of the system

The Chilean pension system was reformed during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973-1988). In 1981, the reform meant to go from a pay-as-you-go system to a private individual accounts system. The system was later reformed twice, in 2002 and 2008, under democracy.

The previous system was composed by institutions called “Cajas de Previsión” (union pension funds and banks), which collected contributions from workers in order to deliver a set of benefits to their affiliates. These Cajas were in charge of providing health services, disability pensions, and retirement pensions. By 1979 the system had 35 Cajas and 150 retirement plans. Cajas were based on workers’ occupations (or industries) so individuals from different occupations were allocated into different Cajas. Benefits were fairly similar within each caja, but there were important differences in pension benefits across Cajas. Not surprisingly, given the heterogeneity between Cajas, the overall system was highly segregated and its was especially bad for low income workers.

The system relied on high contributions from both workers and employers. These contributions ranged from 9.5% to 18.8% of workers’ income and from 7% to 44.4% of workers’ salaries charged to employers. These previous rates were much higher than current figures, even when retirement ages were 60 for women and 65 for men, and life expectancy was lower than today. Thus, the system seemed to be sustainable for itself.

The pension reform of 1981 was part of a broader set of reforms conducted under Pinochet’s dictatorship. It went from the old system to a system based on individual accounts. The new system was mandatory for new workers and voluntary for workers that were already in the pay-as-you-go system[1] (i.e. once you changed, you could not go back). In the new system, contributions were made only by workers. In order to make the system attractive, the contribution rate was reduced to 10% of the labor income. These funds enter into an individual account that is managed by a Pension Fund Administrator (AFP, in Spanish). In the beginning, these AFPs charged a high monthly fee to manage the funds; however, they had fallen from 5% of labor income to only 0.47% in more recent times. Retirement ages remained the same despite improvements in life expectancy, but an early retirement scheme was introduced.

The AFPs can invest in domestic or foreign capital markets. Their investments are highly regulated by type of asset, risk level, or countries. Since 2002, affiliates can choose to invest in up to five different funds with different risk profiles.

In 2008, because of low pension benefits, a state-funded solidarity system was introduced using fiscal revenues. These public funds are used for two purposes: to ensure that pension benefits are higher than or equal to a minimum pension and to provide pension benefits to the elderly who did not contribute enough to the system. Finally, the reform also added a voluntary contribution to the pension fund, complemented by a state-provided subsidy. Hence, the current system is a mixed one based on three pillars: the compulsory contribution pillar, the voluntary contribution pillar, and the solidarity pillar.

The current state of the system

The functioning of any pension system is mainly determined by two factors: how the labor market works and the demographic structure.

The first factor is the Chilean labor market, which is characterized by low participation rates, especially among women, the young, and the elderly (above 60 years old). These low rates are concentrated among unskilled workers who are more likely to earn both lower and more volatile incomes. According to CASEN 2013[2], labor force participation was 71% for men and 48% for women. Moreover, only 53.3% of employed men held job contracts and this figure is 29.1% for women. Low labor market participation means lower pension benefits, regardless of the system (pay-as-you-go or individual accounts).

Another feature of the Chilean labor market is the low proportion of workers that contributes to the pension system at any time. Only workers with a formal contract contribute to the pension system. One third of the population hold such contracts. This low proportion implies that, for a given worker, the average time of contributing to the system is 22 years for men and for 15 women. Evidently, this period is not long enough because pension benefits are supposed to finance retirees’ consumption for 19 years in men and 29 years in women, according to current life expectancy figures. With these figures in mind, it is easy to see that in the long run, pension benefits will not be higher unless effective policies are implemented to address the weaknesses of the labor market.

The second factor is an ageing population, which is challenging every pension systems around the world and Chile is not the exception. Rapid reductions in fertility rates, coupled with increases in life expectancy, imply that the share of the elderly would steadily grow. This age group has rapidly increased its relative size in recent decades. In 1990, the population of 60+ years was only 9% of the entire population. It increased to 15% in 2015; and it is expected to reach 30% in 2050. This rapid growth means that the quantity of elderly will increase from 2.7 to 6.3 million, making the ratio of active to old to fall from 5 to 1.8. To get a sense of the consequences of an ageing population, consider the following hypothetical scenario: If the active population needed to contribute 20% of their income to a pay-as-you-go scheme in 1990, then in 2050, it would be necessary for active workers to finance it with more than 50% of their income. This is clearly unfeasible.

The combination of a weak labor market and a rising elderly population implies that pensions have been disappointingly low (relative to the promise made when the system was introduced). The coverage (workers that actually contribute) of the system reaches to 65% of the workforce. Contributions are highly unequal. Workers in the tenth income decile contributed 87% of their working life, while individuals in the bottom quartile contributed only 12%. This is mainly because of a precariousness of the labor market, in which low wages are associated with informality, self-employed workers and unemployed.

In 2013, the system delivered pension benefits to 84% of the elderly population. This figure increased from 79% in 2006 following the introduction of the Basic Solidary Pension (BSP), the minimum level of pension any elderly should receive.

The replacement rate measures the pension benefit as a fraction of the mean income in the ten years before retirement. The current rates are 60% for men and 31% in women if we include the BSP. The corresponding figures without the BSP would be 48 and 24%, respectively. A commission of experts -gathered to analyze the pension system – projected that these figures will be 41% and 34% for the period 2025-2035.[3] These levels are low compared to the average OECD country which is around 60%.[4]

The discussion

Any policy reform to the pension system should consider safety nets for the elderly, including improved health care and housing assistance. Apart from that, the pension system must follow some criteria. The two most important ones are that it must deliver reasonable pensions and be sustainable.[5]

- Chile must move to a State owned and managed pay-as-you-go system and the funds we have already accumulated should go to a common single fund to finance high pensions.

Supporters of this proposal do not want to go back to the old system of “Cajas”. Instead, they propose to concentrate all contributions in a unique state-managed fund, so that the government is in charge of collecting taxes or contributions and delivering pension benefits to retired people. This proposal may be feasible in the short-run (as the system is already funded) but will be unsustainable in the long-run, because the demographic structure implies that at some point in the near future, the total amount of pension benefits would require working people to contribute, at least, 50% of their earnings, as we mentioned before. Hence, the only way to have a sustainable pension system is to increase savings of young workers now. In fact, the whole Chilean economy should start saving more now.

Also, we must decide how and where to save. Some people argue that is not morally acceptable to invest pension funds in the private sector, financing large or foreign firms because these companies usually collude with competitors or pay low wages to their employees. In the first argument, we assert that companies that engage in illegal practices of any type should be sued and prosecuted by the law regardless of whether they receive pension funds or not. In the second argument, we think that their analysis on wages is flawed. They claim that it is not acceptable to invest in firms that pay low wages because this exacerbates the problem of low wages which, in turn, perpetuates low pensions. This is hardly true. On the one hand, employees of large companies usually earn higher wages and are much more likely to have a formal job contract than workers in smaller firms. On the other hand, pension funds flowing to large companies may reduce their financial costs (through better cost structure) which could mean that these firms can pay higher wages, and not the other way around. In any case, the objective of supporting small firms and funding entrepreneurs is desirable but it is not the goal of pension systems in any part of the world. Promoting entrepreneurship is beyond the scope of any pension system and hence governments should have tailored policies for this end (one tool for one target). If we want higher pension benefits, funds should go to companies with high returns, independent of their ownership or size.

We think that these funds should be mostly privately managed. In order to ensure profitability and sustainability, we need professionals in charge of them. Since these funds determine not only economic stability for each individual, but also for the whole economy, managers must be experts, with solid technical skills. In this way, we prevent politicians from using these funds for short-run purposes that go beyond the scope of the pension system. Having said this, we acknowledge that the management of funds must be highly regulated, even though it may go against maximizing economic returns.

Finally, we argue that the state must be in charge of complementing the pensions that do not reach a minimum level. This must be financed with part of the individual contribution pillar (not all) and fiscal revenues.

- It is a problem of parameters and not of how the system is organized.

Even after solving the problems related to the labor market (low participation, low coverage) and demographic structure, we claim that, at least in the short run, it is necessary to change the parameters of the system.In our opinion, the system does not have enough funds. More money is going out than coming in. And this gap will widen as time goes by.

The contribution rate of 10% of income is too low. We propose to gradually increase this rate to between 15 and 20%. These additional funds would go into both individual accounts and the solidarity pillar, in order to ensure higher pension benefits for everybody.

Efforts should be made in order to ensure that independent workers, who account for 25% of the labor force, contribute to the system. This implies that contributions should be based on total personal income and not only labor income. AFPs must provide innovative contribution schemes for independent workers, taking into account that their incomes are relatively more volatile than that of employees. Given that most new workers are entering the labor market later (the time they need for college and post-graduate education) and have higher life expectancy, we also propose to progressively extend retirement ages from 65 to 70 for men and from 60 to 70 for women.

We also need to encourage competition among AFPs in order to obtain higher efficiency and better performance. In order to lower the administration fees, we would maintain the public bids of new workers to the system. As more workers join the system, we could expect lower fees and higher returns due to economies of scale.

Currently, each fund manager must reach a capital requirement of 1% of the total amount it is administering, and invest it in the same portfolio of their clients. We think this is not enough to align the incentives of the managers with their client’s, so instead, we propose to link monthly fees to AFP’s performance. This is because sometimes returns could be negative due to mismanagement of the AFP. Also, managers must improve the information delivered to their clients, regarding how their funds are invested and the fees payment. Hopefully, this increased transparency, coupled with better incentives, will improve the returns and the alignment of AFP profits with individual returns. However, these measures would imply that AFPs will not take enough risks and may reduce the returns on funds. To overcome that, we propose to open pension funds investments to a broader set of assets, and an obvious example of this is Public Works.

Finally, we propose to enhance the capabilities of the permanent committee for the evaluation of the pension system. The goal of this committee should be to assess the performance and sustainability of the system on a regular basis. It should be in charge of setting the parameters: amount of contributions, retirement age, and the way the system invests the resources. This committee should be independent of the regulator and the government.

[1] Military personnel had a special different treatment.

[2] CASEN: Encuesta de Caracterización Socioeconómica, in English “Socioeconomic Characterization Survey”.

[3] Its report is the source of most of the figures shown in this article. http://www.comision-pensiones.cl/Documentos/Informe

[4] According to “Pensions at a Glance”, OECD 2015. See the report in http://www.oecd.org/publications/oecd-pensions-at-a-glance-19991363.htm

[5] Respect to OECD pensions’ levels.

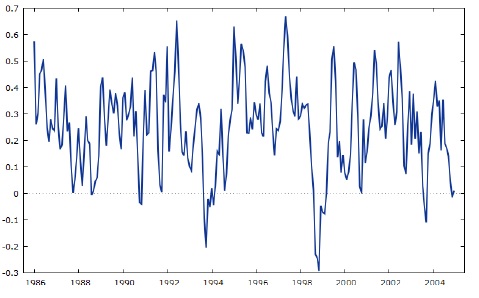

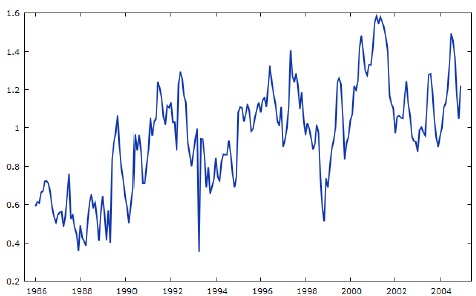

![]() Relative convergence: it is analogous to the previous concept but, in this case, transportation cost does not completely disappear. It can be expressed as:

Relative convergence: it is analogous to the previous concept but, in this case, transportation cost does not completely disappear. It can be expressed as:![]() Therefore, absolute convergence is a specific case of relative convergence for the case of α=0, which is mainly that transportation costs are equal to zero.

Therefore, absolute convergence is a specific case of relative convergence for the case of α=0, which is mainly that transportation costs are equal to zero. Source: Own elaboration in previous work [1]

Source: Own elaboration in previous work [1] Source: Own elaboration in previous work[1]

Source: Own elaboration in previous work[1]