Post by Facundo Abraham ’16 and Alberto González de Aledo Pérez ’16, current master’s students in the Barcelona GSE International Trade, Finance, and Development Program.

In 2001 it was widely predicted that in a decade’s time, Brazil, Russia, India and China (dubbed the BRICs) would become leading economies in the world, reshaping the global economy and international institutions. Now, more than a decade later, with the BRICs economies slowing down, these countries have lost momentum and there is doubt whether the BRICs’ will actually take over the world economy. The most paradoxical case is perhaps Brazil. Once seen as the country of the future and put forward as an example of economic success, it has now sunk into recession, high inflation and corruption scandals. So, what happened to Brazil? How did the country go from being the pampered child of international investors to a pariah in just a decade? What we argue is that when the figures are examined, they reveal that since 2001 the economic performance of Brazil was far from spectacular and, in fact, rather disappointing. Thus, the negative shift in expectations towards Brazil should come as no surprise.

We will focus on a simple growth accounting exercise. Simply stated, we assume that output in an economy is produced under a Cobb-Douglas production function in which capital and labour are used as inputs together under a certain technology/productivity. Mathematically:

![]()

Then, to eliminate the effect of country size on output, we can define output per worker as:

![]()

In this way, we can see that growth can be derived from two sources: technological progress and capital accumulation such that:

![]()

Did Brazil keep up pace with the other BRICs?

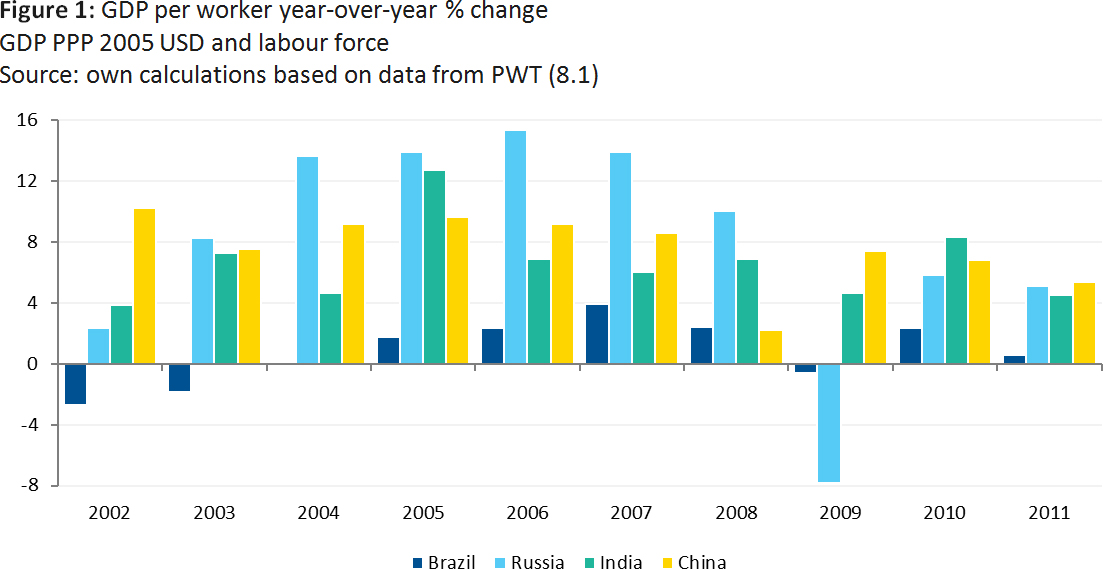

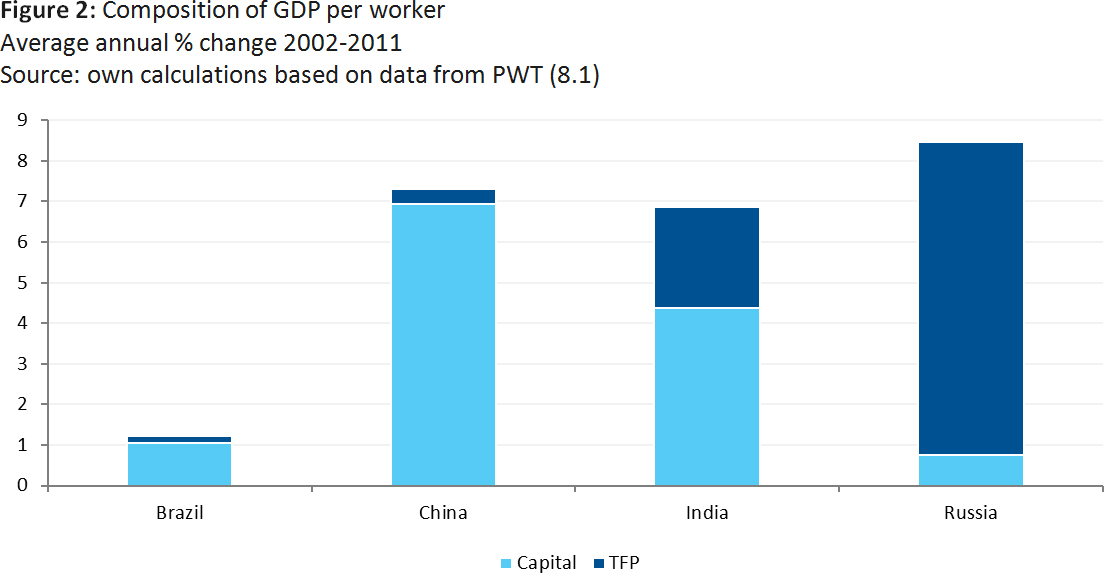

The first question we need to answer is whether Brazil was experiencing high growth rates like the rest of the BRICs. The data shows that after 2001, the economy of Brazil lagged behind the other BRIC countries. Between 2002 and 2011 output per worker grew on average only 1.2%, far behind the 8.5% in Russia, 7.3% in China and 6.9% in India. Comparing the growth rates year by year clearly shows the sluggish performance of Brazil among the BRICs.

Going further, we can ask ourselves how did Brazil perform related to capital accumulation and productivity growth. In the period 2002-2011 capital accumulation in Brazil was low with the capital per worker ratio growing on average by 2.3%. This figure is far less than the 11.4% in China and 8.6% in India. Yes, Brazil did better than Russia where the ratio increased by 1.9% yearly. However, Russia beat Brazil by far in productivity growth. While in Russia productivity grew on average 7.7% per year, in Brazil it grew by only 0.2%. Brazil was the BRIC country with lowest productivity growth being also behind India (2.5%) and China (0.4%).

But was Brazil doing better than before?

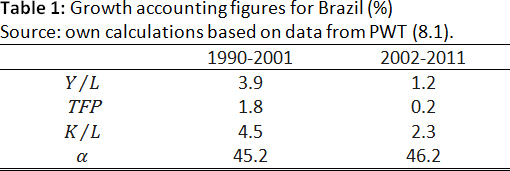

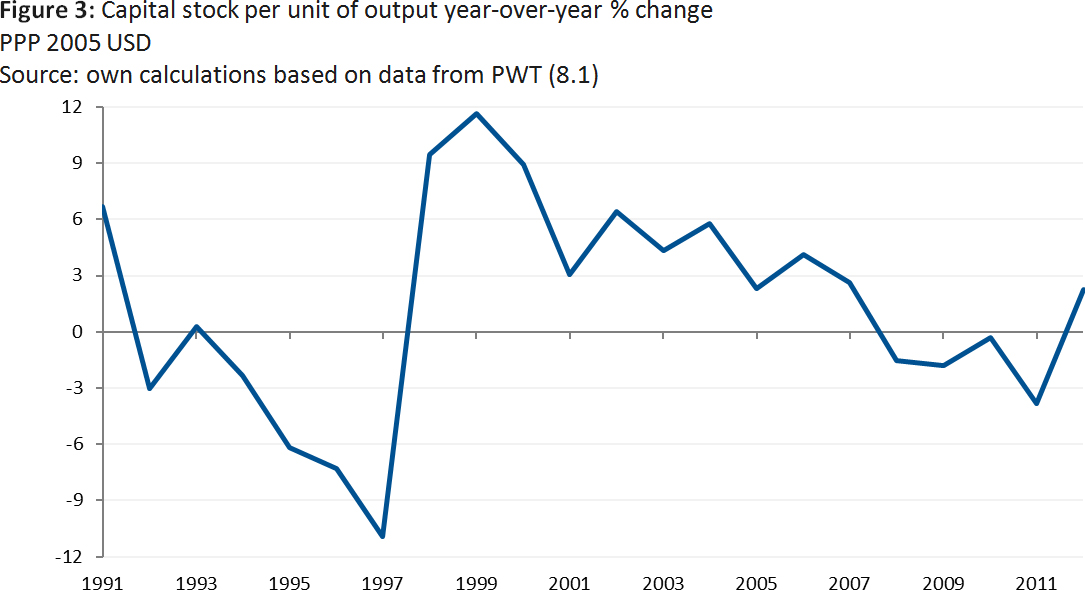

Even though Brazil could have been doing worse than the rest of the BRICs, maybe Brazil was experiencing an economic boom compared to the previous years, which motivated the positive change in investor sentiment. However, again the data shows that Brazil performed worse since 2001 than in the 90s. Between 1990 and 2001 the Brazilian output per worker grew at 3.9% on average per year, with capital per worker growing at 4.5% and productivity at 1.8%. As shown below, these figures are better than the ones from 2002 onwards.

An interesting observation comes from analysing the capital intensity ratio, measured as capital stock over output. In the growth literature, as an economy moves towards its steady state, the growth rate of the capital to output ratio diminishes and eventually becomes zero in the steady state. Thus, the growth rate of capital to output is called “transitional growth” while the growth rate of productivity is the long-term growth. Looking at the data, the growth of the capital intensity ratio in Brazil dropped over recent years, being near to zero. This behaviour is more consistent with an economy that is exhausting its growth rather than with an economy entering a period of high growth.

More Latin American, less BRIC

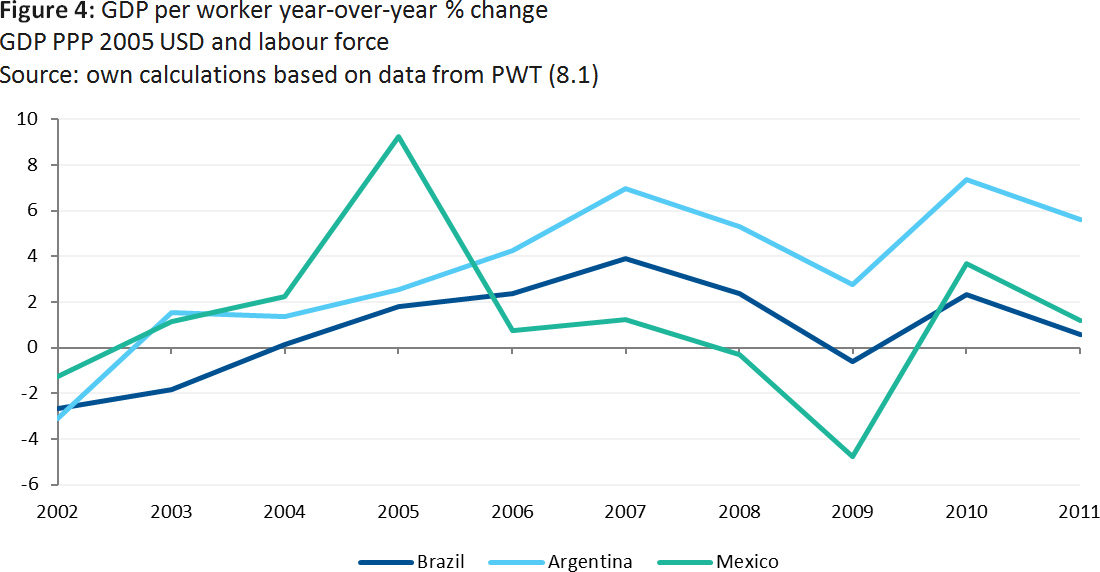

A final analysis consists in comparing the economic performance of Brazil to the other two big Latin American economies: Argentina and Mexico. Brazil’s output per worker growth of 1.2% per year was less than the 4.2% in Argentina and 1.5% in Mexico. In addition, comparing the growth rates for each year shows that the behaviour of the three economies was very similar and, moreover, Brazil performed worse than Argentina.

This simple comparison could support the view that Brazil does not seem to have behaved like the other BRICs, being closer in performance to its Latin American neighbours. This observation is important considering that while Brazil was a star in the international markets, Mexico and Argentina were viewed with far more pessimism.

Concluding remarks

This growth accounting exercise is useful in providing simple insights that help us understand more clearly what has happened to Brazil over the last decade. There are many reasons behind the rise and fall of the Brazilian economy and it is not the aim of this article to account for them all. The results are enlightening because they show that, after being included in the BRICs and brought into the spotlight of financial markets, Brazil’s economic performance was modest compared to the other BRIC countries and even to its own past performance. Thus, even before the start of the crisis, the Brazilian economy showed some weaknesses that should have raised red flags early on.

About the authors

Facundo is a current student at the International Trade, Finance and Development program. Previously he worked in consulting projects on financial regulation and supervision in Latin America. He graduated in Economics from Universidad Torcuato di Tella. Connect with Facundo on Linkedin.

Facundo is a current student at the International Trade, Finance and Development program. Previously he worked in consulting projects on financial regulation and supervision in Latin America. He graduated in Economics from Universidad Torcuato di Tella. Connect with Facundo on Linkedin.

Alberto is a current student at the International Trade, Finance and Development program. He is a former Economist in BBVA’s Economic Research Department. He holds a BSc in Economics from Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. Connect with Alberto on Linkedin or follow him on Twitter.

Alberto is a current student at the International Trade, Finance and Development program. He is a former Economist in BBVA’s Economic Research Department. He holds a BSc in Economics from Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. Connect with Alberto on Linkedin or follow him on Twitter.

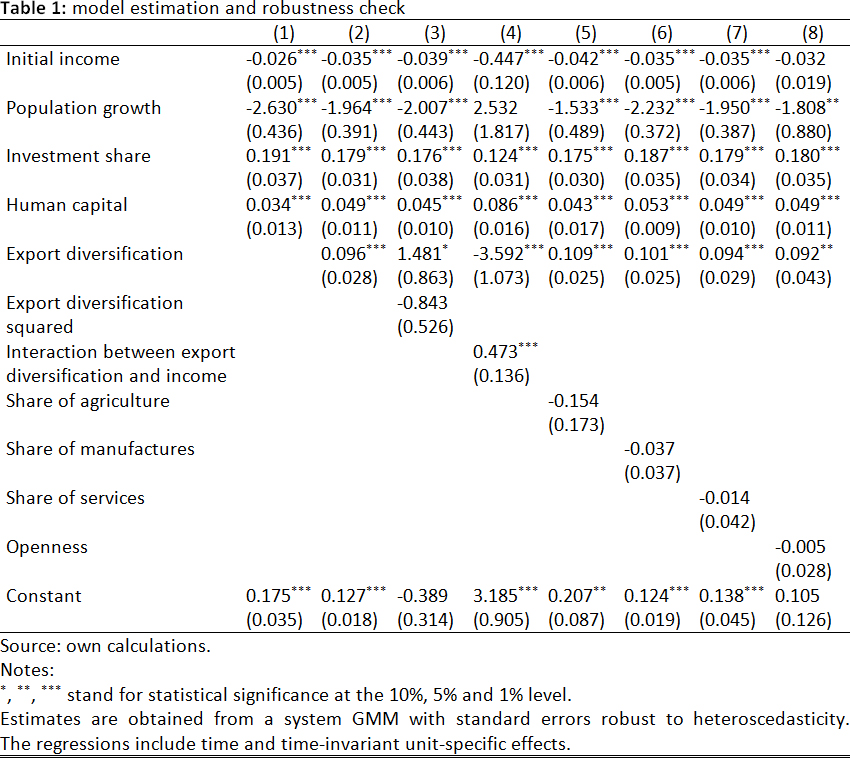

Column 1 in Table 1 presents the estimation for the augmented Solow model. The computed coefficients are significant and have the expected sign. There is evidence from column 2 that export diversification has a positive and significant effect on GDP per capita growth as has already been predicted in previous studies. Columns 5 to 8 supports the robustness of export diversification with the inclusion of different control variables. If openness is entered as it is in column 8, initial income becomes not significant. The performance on this indicator varies across countries in the sample. In the case of the Philippines and Malaysia there is a downward trend. However, in the former the initial values were remarkably high. China has also experienced a decrease in its level of openness in the aftermath of the crisis.

Column 1 in Table 1 presents the estimation for the augmented Solow model. The computed coefficients are significant and have the expected sign. There is evidence from column 2 that export diversification has a positive and significant effect on GDP per capita growth as has already been predicted in previous studies. Columns 5 to 8 supports the robustness of export diversification with the inclusion of different control variables. If openness is entered as it is in column 8, initial income becomes not significant. The performance on this indicator varies across countries in the sample. In the case of the Philippines and Malaysia there is a downward trend. However, in the former the initial values were remarkably high. China has also experienced a decrease in its level of openness in the aftermath of the crisis.