I started to work on remittances around three years ago when I joined my current organization, the Centre for Financial Regulation and Inclusion (or Cenfri in short) as a researcher. We are an independent, not-for-profit think-and-do-tank based in Cape Town, South Africa, trying to answer complex questions around the role of the financial sector in improving individuals’ welfare in emerging economies. Remittances is one of our key focus areas and we have received donor funding from Financial Sector Deepening Africa (FSDA) to understand why the cost of sending funds into Africa is still the highest in the world.

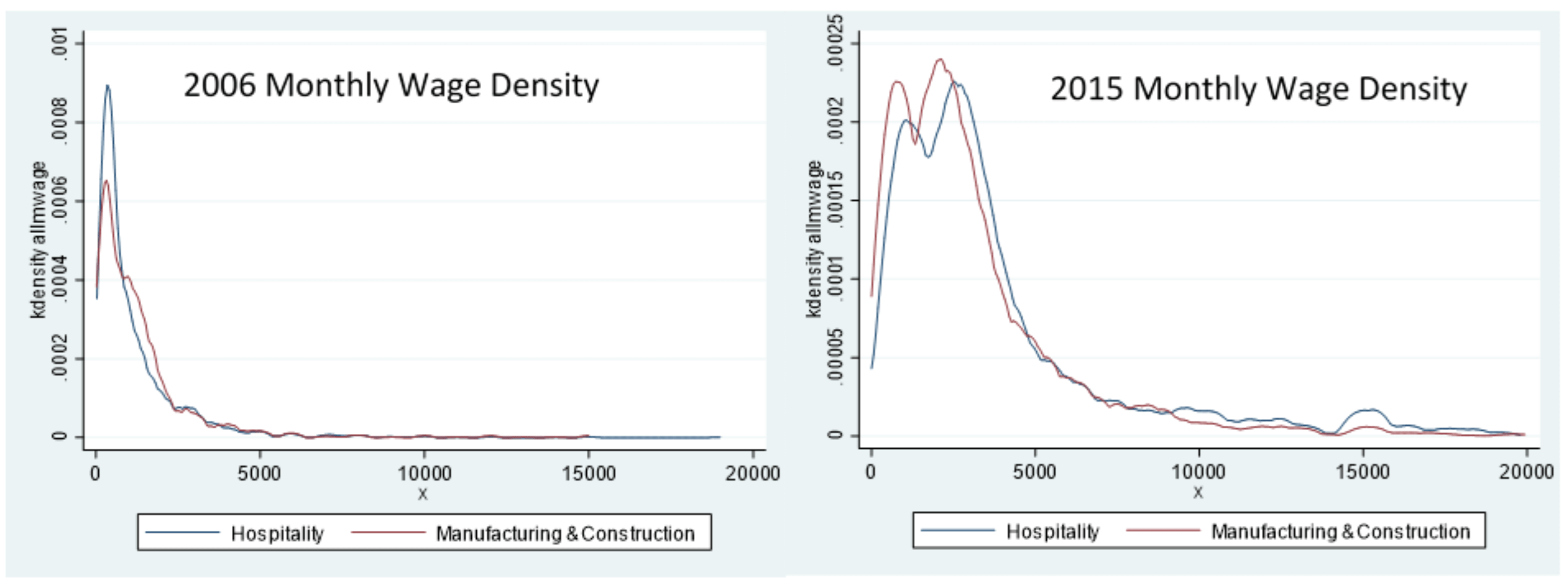

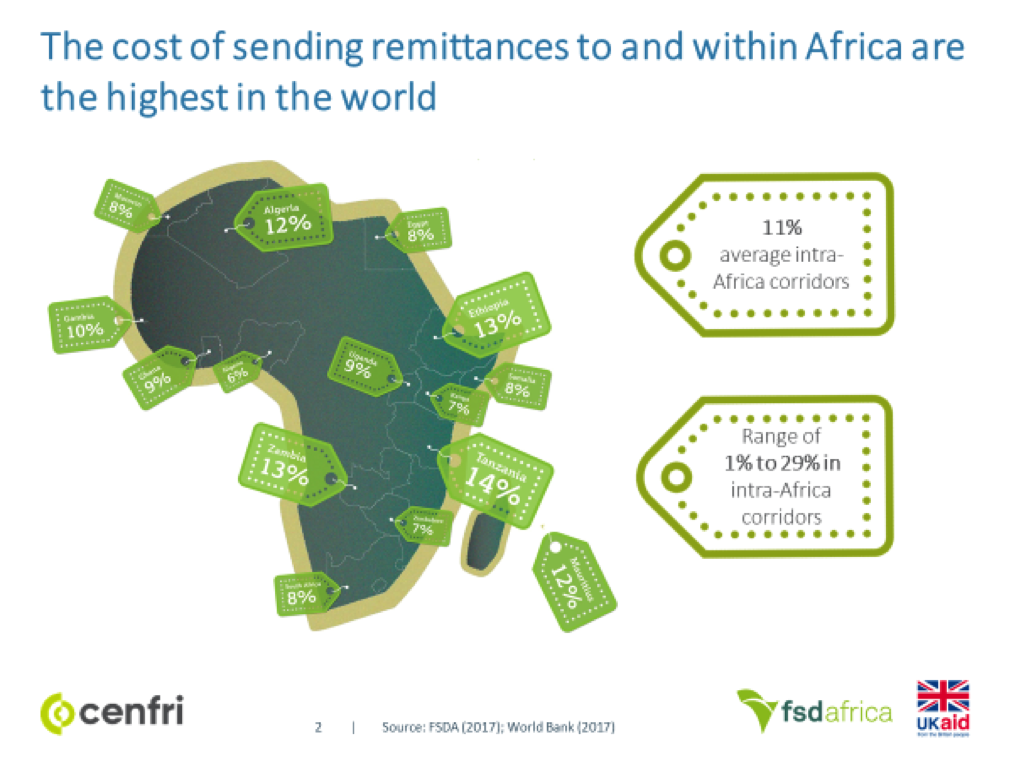

According to the World Bank, the average cost of sending remittances globally stood at just under 7% of the total value of the transfer in the first quarter of this year; in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), consumers had to pay on average 9.25% – by far the most expensive region in the world. The SDGs want to bring down the cost to between three and five percent. Most disturbingly, intra-Africa transfers can cost way more than 15% in some corridors, even when the countries are neighbours (e.g. Nigeria and Cameroon where a transfer can cost 15%). The following graphic shows the average prices some time in 2017 between the UK and selected African countries.

When one considers that around 80% of African migrants stay within Africa, this is an incredibly high burden in terms of cost that reduces the positive impact of these essential flows for recipients. Many migrants are therefore forced to use informal mechanisms that are often cheaper, more trusted and more convenient. Yet informal mechanisms can be fronts for illicit financial flows, including money laundering and the financing of terrorism. They also indirectly influence competition as they mask the true size of a remittance corridor, deterring providers from entering the market.

Formal remittance flows are now higher than the value of official development assistance (ODA) and foreign direct investment (FDI). They have shown to have significant positive impact as they flow directly in the hands of those that rely on these funds as a primary source of income, and they tend to be more stable than ODA or FDI.

Based on all this evidence, FSDA asked us to understand the cost drivers and why it is still so expensive to send money to and within the continent despite all the innovations in the FinTech space with apps from players such as WorldRemit. We embarked on a journey to collect evidence through stakeholder interviews (with private sector players such as money transfer organisations, banks, FinTechs, and post offices, as well as regulators, policy makers and experts), mystery shopping, speaking to consumers, and ploughing through existing literature. We travelled to important remittance markets such as Nigeria, Ethiopia, Côte d’Ivoire and Uganda last year to understand the situation on the ground.

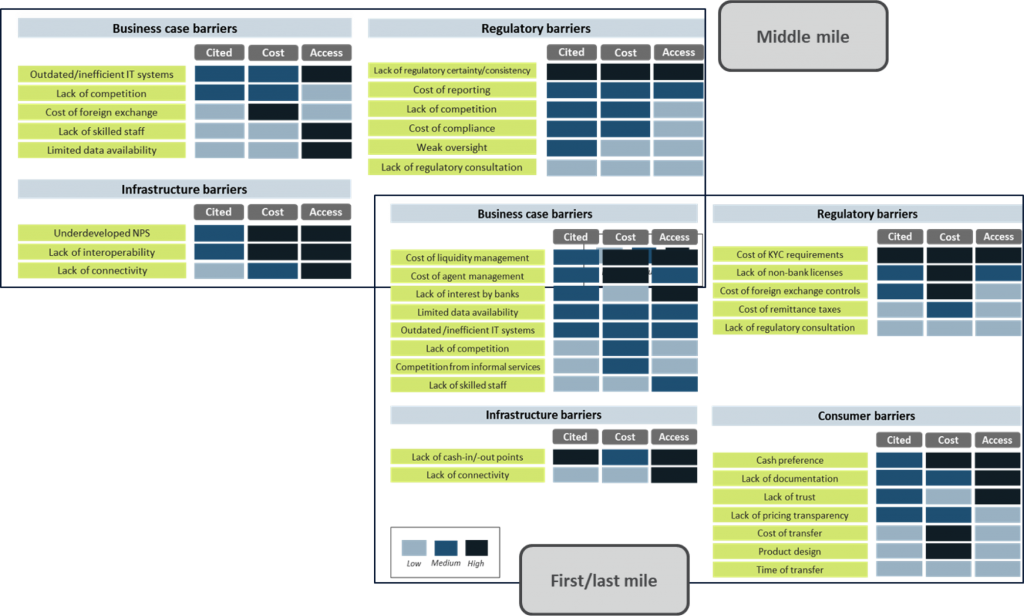

What I’ve learned since then is that remittances are an incredibly complicated business. It consists of providers in the first mile (where cash sending happens), the middle mile (where the processing of payments happens) and the last mile (where the recipient collects the money). The value chain is therefore very long and brings with it not only partnership complications but also technical issues. Cross-border money transfers are heavily regulated due to money laundering fears and severe risk exposure, but especially in Africa capital outflows of any kind are also heavily controlled in many markets still. To get a money transfer license can sometimes take a decade, we heard from some providers.

Overall, there were many interesting insights but at the end of the day we narrowed the reasons for the high costs down to four categories: business case barriers, regulatory barriers, infrastructure barriers and consumer-facing barriers. We then evaluated the number of citations and their impact on cost and access for the consumer to show how severe the barrier is for both providers and consumers:

From these insights we produced a range of reports, that you can access here, if you are interested, with the aim to disseminate them at key events and bring them into relevant discussions with the various stakeholders.

One avenue we are pursuing is to reduce the regulatory

burden for providers to stimulate competition, especially in intra-Africa

corridors. Many cross-border corridors are still dominated by one or two

companies such as Western Union or MoneyGram that can set their prices freely.

They are helped by the regulation as the licensing requirements in some cases

can be incredibly high. For example, you may need to show capital of USD 20

million, be operational in at least seven countries for at least ten years. Of

course, none of the newer players that can offer cheaper remittances through

using apps, for example, can meet all

these requirements.

We were therefore on the hunt to influence regulators to revise some of the regulations. And a lot of regulation touches cross-border remittances: payment system act, banking act, foreign exchange act, agent banking regulation, e-money regulation, telecommunications regulation, cross-border transfer regulation etc – the list goes on and on. Every country seems to have their own set of rules and regulations that need to be made interoperable or at least harmonise to reduce the regulatory burdens in a value chain that can cross many jurisdictions. Definitely not an easy task! Many African countries are still heavily dependent on natural resources, such as Nigeria on oil for example. Their exchange rate with the dollar is fixed by the central bank. Yet, the Nigerian Naira is overvalued, leading to a parallel shadow market where one can get better rates for dollars on the streets of Lagos, impacting the use of formal remittance channels. But of course, the regulator is very concerned with financial stability and the impact a devaluation could have on foreign exchange reserves, inflation etc. Attracting more formal remittances does not sway the regulator enough to change the exchange rate policies. All of these realities need to be taken into consideration when approaching the regulators to try and achieve change based on research, and of course protocols play a huge role.

As part of this effort to reach regulators and based on the research we had done, I was recently invited to attend the inaugural meeting of experts, organized by the African Institute for Remittances (AIR), which is a programme established by the African Union. We were called from all over the continent based on our research and professional experience to build a cohort that would give technical assistance to willing African regulators. Last month we met in Mombasa, Kenya, and learned more about the planned interventions. On the one hand, we want to achieve better remittance data quality in the individual countries as the data can be questionable, but on the other hand we want to assist with writing the right kind of regulation that fosters innovation, reduces cost without reducing the access for consumers, and incentivise the uptake of formal remittance mechanisms.

I learned which data point to allocate to which balance of payment code at the central bank to make sure there is consistency across countries. I also learned how we will go about understand the regulatory background, as of course there is a difference between de jure and de facto regulation, i.e. we need to understand how regulation is interpreted from a stakeholder point of view.

So far it has been an exciting journey to see how we can take our insights into regulatory change. Some countries have already shown interest in being assessed and assisted and we will receive a list of our country missions as the expert cohort soon. Judging from our past work with regulators, this process can take many months, years if not decades but the potential impact of such fundamental changes is immense, especially for the individual person on the ground. System-level impact takes patience and perseverance.

ITFD taught me to be precise and on-point with my research to effect change – policy makers do not want to read 300 pages no matter how well-researched the material is. Insights need to be relatable and digestible, yet you also need to be able to raise funding for important interventions even if they seem cumbersome. We are lucky that FSDA has such a mandate and I look forward to continuing this journey with them and the African Union. Hopefully I will be able to report a significant drop in remittance prices due to regulatory change soon..ish.

Antonia Esser ’11 is an Associate at Cenfri in Cape Town, South Africa. She is an alum of the Barcelona GSE Master’s in International Trade, Finance, and Development.