The following job market paper summary was contributed by Francesco Amodio (Economics ’10 and GPEFM). Francesco is a job market candidate at UPF. He will be available for interviews at the SAEe (Palma de Mallorca, December 11-13) and ASSA (Boston, January 3-5) meetings.

The following job market paper summary was contributed by Francesco Amodio (Economics ’10 and GPEFM). Francesco is a job market candidate at UPF. He will be available for interviews at the SAEe (Palma de Mallorca, December 11-13) and ASSA (Boston, January 3-5) meetings.

Management matters. Differences in management practices can explain a considerable amount of variation in firms’ productivity and performance, both across and within sectors and countries (Bloom and Van Reenen 2007, 2010, 2011). Several studies have shown how human resource management and incentive schemes may affect overall productivity by making the effort choices of coworkers interdependent (Bandiera, Barankay and Rasul 2005, 2007, 2009). In more complex settings, however, workforce management features may interact with production arrangements and jointly determine the overall result of the organization. Understanding the nature of this interplay is of primary importance in the adoption and implementation of productivity-enhancing management practices.

In my job market paper, coauthored with Miguel A. Martinez-Carrasco, we shed light on these issues by focusing on settings where workers produce output by combining their own effort with inputs of heterogeneous quality. This is a common feature of workplaces around the world. For instance, in Bangladeshi garment factories, the characteristics of raw textiles used as inputs affect the productivity of workers. Similarly, the purity level of chemicals affects the productivity of researchers in biological research labs.

Now, suppose we pick a worker and endow her with higher quality inputs, thus increasing her productivity. What happens to the productivity of coworkers around her? Do they exert more effort, or do they shirk? How do human resource management features shape their response?

The setting

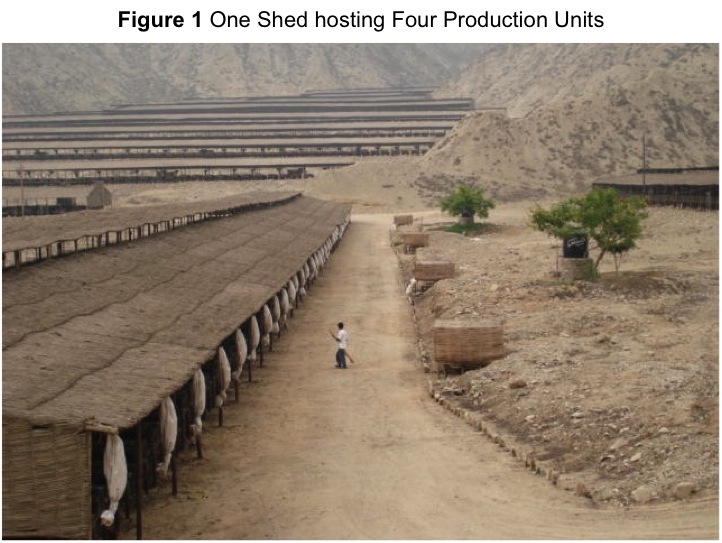

In order to answer these questions, we collected data from an egg production plant in Peru. Production is carried out in production units located one next to the other in several sheds. In each production unit, a single worker is assigned as input a batch of laying hens. Workers’ main tasks are to feed the hens, to maintain and clean the facilities, and to collect the eggs. The characteristics of the hens and worker’s effort jointly determine productivity, as measured by the daily number of collected eggs. Figure 1 shows the picture of one shed hosting four production units. Notice how workers in neighboring production units can easily interact and observe each other.

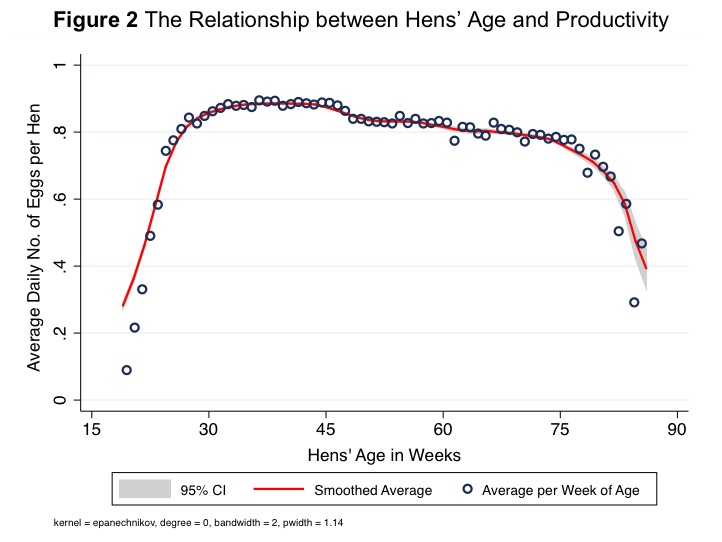

The specific features and logistics of this setting generate the quasi-experiment we need in order to answer the questions of interest. All hens within a given batch have very similar characteristics. When reaching their productive age, they are moved to one production unit and assigned to the corresponding single worker who operates the unit. After approximately 16 months, they reach the end of their productive age and are discarded altogether. The age of hens in the batch exogenously shifts productivity. Indeed, Figure 2 shows the reversed U-shaped relationship that exists between hens’ age and productivity. Perhaps more importantly, the timing of batch replacement varies across production units, generating quasi-random variation in the age of hens assigned to workers.1 We can thus exploit these differences to credibly identify the causal effect of an increase in coworkers’ productivity – as exogenously shifted by coworkers’ hens age – on own productivity, conditional on own hens’ age.

Main Results

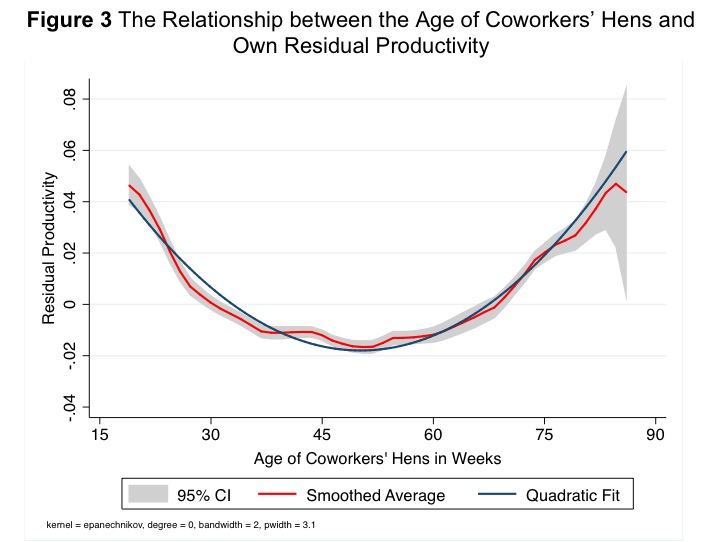

We find evidence of negative productivity spillovers. The same worker, handling hens of the same age, is significantly less productive when coworkers in neighboring production units are more productive, with variation in the latter being induced by changes in the age of their own hens. This finding is pictured in Figure 3, which shows that a U-shaped relationship exists between own productivity and coworkers’ hens age. In other words, workers exert less effort and decrease their productivity when coworkers are assigned higher quality inputs.

We also find similar negative effects on output quality, as measured by the fraction of broken and dirty eggs collected over the total number of eggs. Furthermore, we find no effect of an increase in the productivity of coworkers located in non-neighboring production units or in different sheds, suggesting that workers only respond to observed changes in coworkers’ productivity.

The role of HR

Why do workers exert less effort when coworkers’ productivity increases? Our hypothesis is that the way the management processes information on workers’ productivity in evaluating them and taking employment termination decisions generates free ride issues among coworkers. When observed productivity is only a noisy signal of workers’ exerted effort, the management combines available signals and best guesses the level of effort exerted by the worker. Even when observable input characteristics can be netted out, individual signals are still imperfect, and possibly excessively costly to process. The management thus attaches a positive weight to aggregate or average productivity in evaluating a single worker. As a result, workers free ride on each other.

In order to test for this hypothesis, we collected employee turnover data from the same firm. As expected, we find that the likelihood of employment termination is lower the more productive the worker is. More importantly, being next to highly productive workers improves a given worker’s evaluation and diminishes her marginal returns from effort, yielding negative productivity spillovers.

We also find that providing incentives to workers counteracts their tendency to free ride. First, we find no effect of coworkers’ productivity when workers are exposed to piece-rate pay. Second, we collected data on the friendship and social relationship among workers, and find again no effect of coworkers’ productivity when a given worker recognizes any of her coworkers as friends. We interpret this as further evidence that the main result of a negative effect of coworkers’ productivity indeed captures free riding issues, mitigated by the presence of social relationships.

Discussion

Our focus on production inputs and their allocation to working peers represents the main innovation with respect to the previous literature on human resource management and incentives at the workplace. In our case study, the allocation of inputs of heterogeneous quality among workers triggers free riding and negative productivity spillovers among them, generated by the workers’ evaluation and termination policies implemented at the firm.

The analysis of more complex production settings reveals the existence of intriguing patterns of interplay between production arrangements and human resource management practices. Our plan for the next future is to proceed further along this line of inquiry. In a companion paper still work in progress, we investigate both theoretically and empirically how workers influence each other in their choice of inputs while updating information on the productivity of the latter from own and coworkers’ experience.

1 Grouping all observations belonging to the same shed and week and taking residuals, we show that the age of hens assigned to coworkers is orthogonal to the age of own hens. We test this hypothesis in several different ways, addressing the issues arising when estimating within-group correlation among peers’ characteristics (Guryan, Kroft, and Notowidigdo 2009; Caeyers 2014). We cannot reject the hypothesis of zero correlation in all cases.

Nicola Cofelice ’14

Nicola Cofelice ’14