By Fernando Fernández (Economics ’13, GPEFM) [1]

“Just when we thought we had all the answers, all the questions changed.” Mario Benedetti

That was my reaction when the 6th Lindau Meeting in Economic Sciences concluded. This meeting occurs every two years and gathers several Nobel Laureates and young economists (graduate students and assistant professors) from around the world. This meeting is certainly the most inspiring academic event I have ever attended.

The meeting took place in the beautiful town of Lindau, next to Lake Constance, in southern Germany between August 22nd and August 27th. During these days, we attended lectures from 18 Nobel laureates in Economics on a wide range of topics: bounded rationality, investment management, pension design, monetary policy, labor markets, morality and markets, political systems, innovation, and econometrics. I will not attempt to summarize these great lectures but all of them were recorded and are available on this link.

I would rather focus these lines on the interactions that occurred outside the “classroom”. Every day the program included lectures, lunch, seminar presentation panel discussions, and dinner.

The first lecture was given by Daniel McFadden [2], and besides the content, something really caught my attention. In the first row of the room (it was actually a theater) you could see the other Nobel Laureates. All were carefully listening to the speaker! They seemed like young students paying attention to an important professor. So the first lesson from this meeting was that we, as researchers, should actively embrace our academic curiosity.

Over lunch, I had the first opportunity to talk to a Nobel Laureate. I was sitting with some friends I just met and were talking about each others’ research. At some point, Bengt Holmstrom asked: “Would you mind if I join you?” We welcomed him, and seconds later he started asking us about our research interests. He soon realized that all of us were doing empirical work and said: “I am the only theorist in this table!”

He listened to all of us, asked some questions (some of them were hard to answer) and even gave us some advice. I was able to confirm that these brilliant economists have a special talent to listen to others, even if they are PhD students struggling with their papers. He was very generous with his time and recommended us to work hard but only on topics that we really cared about. He also advised us not to focus on publishing papers but instead on gaining respect from our peers through our work.

Hours later, I had the chance to sit on the table with Eric Maskin for dinner. He told us about the day he received the call from Stockholm and found out he won the Nobel prize. Then, we talked about US politics, big data, increasing co-authorship in economic journals, and other current issues in academia. As you can imagine, when you are sitting next to a Nobel Laureate you get the feeling that you can ask him any question. Well, these questions (some of them unrelated to economics) arrived and Maskin, very modestly, said : “I know very little about this particular topic, so I cannot have an informed opinion. In fact, you should know that one wins the Nobel prize, not because you know everything, but because you specialize in certain specific topics”. His reaction really impressed me but he was right. He could not be an expert in every topic and he acknowledged it. How many times do we feel the need to have an opinion on everything? The second lesson from this meeting is that we must always acknowledge our limitations and be humble enough to don’t give uninformed opinions.

One of the big questions most PhD students have is the following: where do great ideas come from? Tirole, Hart and Holmstrom provided some light on this issue and their advice was the third lesson. Tirole said two great sources of ideas were talking to people around you (his office was next to Hart’s) and to people outside the academia (practitioners, policy makers and business men). He encouraged us to talk to practitioners because they are facing the real problems we must address, that they have many important questions that remained unanswered and deserve our attention. Holmstrom said that the idea of his well-known model of career concerns (one of the reasons he was awarded with the Nobel prize) came when he has working in a plant in Finland, and had some problems with his manager. He then went to do his PhD and wrote a model to explain the behavior of this manager. In addition, he recommended us to become experts in the literature of our field of interest, not to follow it but to depart from it. After this, Hart said that working with Holmstrom and Tirole was a great way to find ideas. He also suggested us that when doing theoretical work, we should keep models as simple as possible.

James Heckman’s lecture was about the identification problem in econometrics. He was the most enthusiastic person I have ever seen giving an econometrics lecture. And this enthusiasm was quite contagious. Even though he was talking about highly technical and complex conditions for a new interpretation of Instrumental Variable (IV) estimates, I was surprisingly able to follow his lecture and understand the contribution he was making. Or, at least that’s the impression I had. That same day, we had a Bavarian dinner at night, with traditional music, food, and of course, beer. This was the last night of the event and the time to say good-bye to other fellow economists.

After some drinks, I decided to walk back to my hotel, located around 50-minutes away from the place we had dinner. On my way, I ran into Heckman, who seemed a bit confused. He had been walking with other young economists and then he was not sure where to go. I approached him and we realized we had to walk in the same direction. This was quite a unique and unexpected opportunity to talk about his lecture. So I started with my questions and he replied to all of them with great patience and enthusiasm. I could confirmed I had actually understood his lecture. Then, we started talking about the rapid increase in data availability and how big data should influence econometrics. He also told me good stories about his last trip to Barcelona and Peru. Eventually, we arrived at the hotel and said good-bye. This great conversation was the fourth lesson: we should remain enthusiastic even after years of dealing (doing research or teaching) with the same subject.

The fifth lesson is that these people seem very happy doing their jobs. Yes, I know, they are Nobel Laureates, they have already accomplished important professional goals. But it is still surprising how much they enjoy doing research. During lunch time or dinner, when we were able to talk to them more informally, people would usually ask: Which are the questions we should tackle? What fields are relevant now? Most Nobel Laureates seemed to share the view that the relevant questions are the ones you really care about. And if they actually work according to this view, it is not that hard to understand why they look like if they were having fun all the time.

When I was heading to this meeting, I had a lot of questions in my mind and thought the meeting would be an ideal place to get answers. During the meeting, some of my questions were being answered but later I realized that getting answers was not so important. Once the meeting was over, I realized all the lessons I took from it were unexpected. I had misunderstood the purpose of this meeting. I should have not come to the meeting looking for answers. I should have come looking for questions. These highly talented economists are Nobel Laureates precisely because they are extremely good at raising questions. Questions that open new streams of work. Questions that people had overlooked but that deserve careful thinking and attention. Now, two months after the meeting, I realize that all the questions raised by these Nobel Laureates are the reason why this event was so inspiring. Because in research that’s what keeps us working: Questions!

[1] I am thankful to the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Fellowship (through the PODER network) for sponsoring my participation in the meeting.

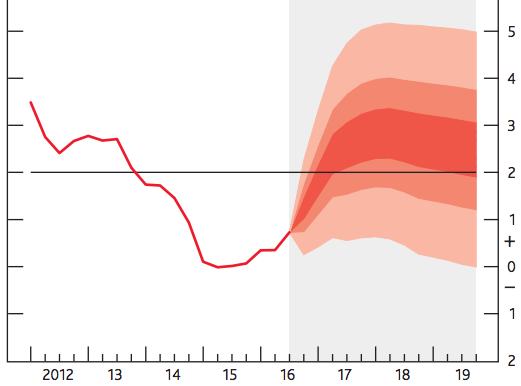

[2] Before McFadden’s lecture, there was a keynote address by Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank.

Editor’s note: In this post, Greg Ganics (Economics ’12 and PhD candidate at UPF-GPEFM) provides a non-technical summary of his job market paper, “Optimal density forecast combinations,” which has won the

Editor’s note: In this post, Greg Ganics (Economics ’12 and PhD candidate at UPF-GPEFM) provides a non-technical summary of his job market paper, “Optimal density forecast combinations,” which has won the