Editor’s note: This post is part of a series showcasing BSE master projects. The project is a required component of all Master’s programs at the Barcelona School of Economics.

Abstract

This thesis studies the impacts of flooding on income and expenditures of rural households in northeast Thailand. It explores and compares shock coping strategies and identifies household level differences in flood resilience. Drawing on unique household panel data collected between 2007 and 2016, we exploit random spatio-temporal variation in flood intensities on the village level to identify the causal impacts of flooding on households. Two objective measures for flood intensities are derived from satellite data and employed in the analysis. Both proposed measures rely on the percentage area inundated in the surrounding of a village, but the second measure is standardized and expressed in comparison to the median village level flood exposure. We find that household incomes are negatively affected by floods. However, our results suggest that rather than absolute levels of flooding, deviations from median flood exposure are driving negative effects on households. This indicates a certain degree of adaptation to floods. Household expenditures for health and especially food rise in the aftermath of flooding. Lastly, we find that above primary school education helps to completely offset potential negative effects of flooding.

Conclusion

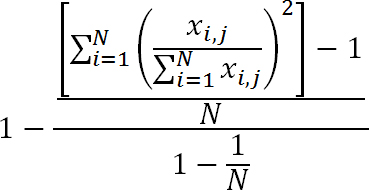

This paper adds to the existing body of literature by employing a satellite based measure to investigate the long-run effects of recurrent floods on household level outcomes. We first set out to identify the causal impacts of flooding on income and expenditures of rural households in Thailand. Next, we explored and compared shock coping strategies and identified potential differences in flood resilience based on household characteristics. For this purpose, we leveraged a detailed household panel data set provided by the Thailand Vietnam Socio Economic Panel. To quantify the severity of flood events, we calculated flood indices based on flood maps collected by the Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency (GISTDA) measuring the deviation from median levels of flooding in a 5km radius around a respective village. The figure below illustrates the construction of the index for a set of exemplary villages that lie in the Nang Rong district of Buri Ram in northeast Thailand.

(a) 2010 flooding in Buri Ram and surrounding provinces. Red lines mark the location of the Nong Rong district.

(b) Detailed overview of flood index construction. Red dot shows the exact location of each village with the 5 km area around each village marked by the red circle.

Our results suggest a negative relationship between floods and per household member income, for both total income and income from farming. Per household member expenditure, however, does not seem to be affected by flood events at all. The only exemptions are food and health expenditures, which increase after flood events that are among the top 10 percent of the most severe floods. The former is likely to be driven by the fact that many households in northeastern Thailand live at subsistence level, and therefore consume their farming produce. A lack of production in a given year may lead these households to substitute this loss by buying produce from markets. Rising health expenditures may be explained by injuries caused or diseases obtained during a heavy flood.

Investigating potential risk mitigation strategies revealed that households with better educated household heads suffer less during flood events. However, this result does not necessarily point to a causal relationship, as better educated households might settle in locations of the village which are less likely to be flooded. While our data does not allow to control for such settlement choices on the micro-spatial level, our findings still provide valuable insights for future policy-relevant research on the effects of education on disaster resilience in rural Thailand. Moreover, our data suggests that only very few households are insured against potential disasters. Future research will help to investigate flood impacts and risk mitigation channels in more detail.

Authors: Zhuldyz Ashikbayeva, Marei Fürstenberg, Timo Kapelari, Albert Pierres, Stephan Thies

About the BSE Master’s Program in International Trade, Finance, and Development

Lecture summary by

Lecture summary by

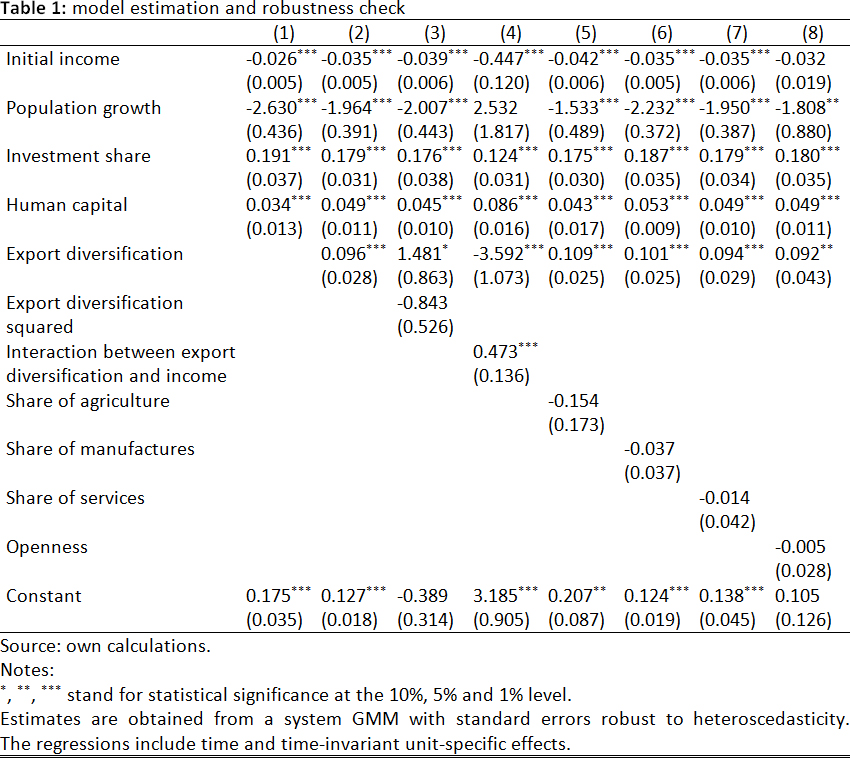

Column 1 in Table 1 presents the estimation for the augmented Solow model. The computed coefficients are significant and have the expected sign. There is evidence from column 2 that export diversification has a positive and significant effect on GDP per capita growth as has already been predicted in previous studies. Columns 5 to 8 supports the robustness of export diversification with the inclusion of different control variables. If openness is entered as it is in column 8, initial income becomes not significant. The performance on this indicator varies across countries in the sample. In the case of the Philippines and Malaysia there is a downward trend. However, in the former the initial values were remarkably high. China has also experienced a decrease in its level of openness in the aftermath of the crisis.

Column 1 in Table 1 presents the estimation for the augmented Solow model. The computed coefficients are significant and have the expected sign. There is evidence from column 2 that export diversification has a positive and significant effect on GDP per capita growth as has already been predicted in previous studies. Columns 5 to 8 supports the robustness of export diversification with the inclusion of different control variables. If openness is entered as it is in column 8, initial income becomes not significant. The performance on this indicator varies across countries in the sample. In the case of the Philippines and Malaysia there is a downward trend. However, in the former the initial values were remarkably high. China has also experienced a decrease in its level of openness in the aftermath of the crisis. Facundo is a current student at the International Trade, Finance and Development program. Previously he worked in consulting projects on financial regulation and supervision in Latin America. He graduated in Economics from Universidad Torcuato di Tella. Connect with Facundo on

Facundo is a current student at the International Trade, Finance and Development program. Previously he worked in consulting projects on financial regulation and supervision in Latin America. He graduated in Economics from Universidad Torcuato di Tella. Connect with Facundo on  Alberto is a current student at the International Trade, Finance and Development program. He is a former Economist in BBVA’s Economic Research Department. He holds a BSc in Economics from Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. Connect with Alberto on

Alberto is a current student at the International Trade, Finance and Development program. He is a former Economist in BBVA’s Economic Research Department. He holds a BSc in Economics from Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. Connect with Alberto on