The relationship between institutions and development is a long-standing topic in economic research. However, economists have tended to only evaluate formal institutions (such as laws and property rights), neglecting the informal (like conventions and norms). This overspecialisation precludes the analysis of ideas and ideologies. Without considering these abstract drivers of development, the space for ethically and politically dangerous explanations of success appears (such as for genetic reasons).

Contrary to recent literature, I argue that informal constraints are actually the basis of institutions and therefore the real generators of growth and development. I show this by examining revolutions – the cauldrons where new systems, ideas, and conventions begin, and old ones end.

The illusion of separation

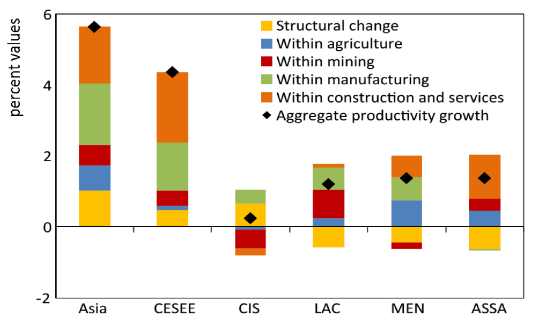

Scholars of comparative development have noted the increasing divergence between developed and developing countries: the gap between Northern and Southern Europe and the underdevelopment of the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa being major examples. Several theories attempt to explain this divergence, considering possible factors such as geographical characteristics and institutional differences. Notably, comparative development has even been attributed to levels of genetic diversity (Ashraf & Galor, 2013).

In particular, the crucial historical link between institutions and development is well known. Famous examples include the advantage of limited royal power (Acemoglu, 2005); reformed constitutional arrangements and strengthened property rights (North & Weingast, 1989); and the balance of power between merchants and princes (De Long, 1993). Yet, these studies put their emphasis on formal rules, neglecting the norms, ideas and ideologies that underwrite them.

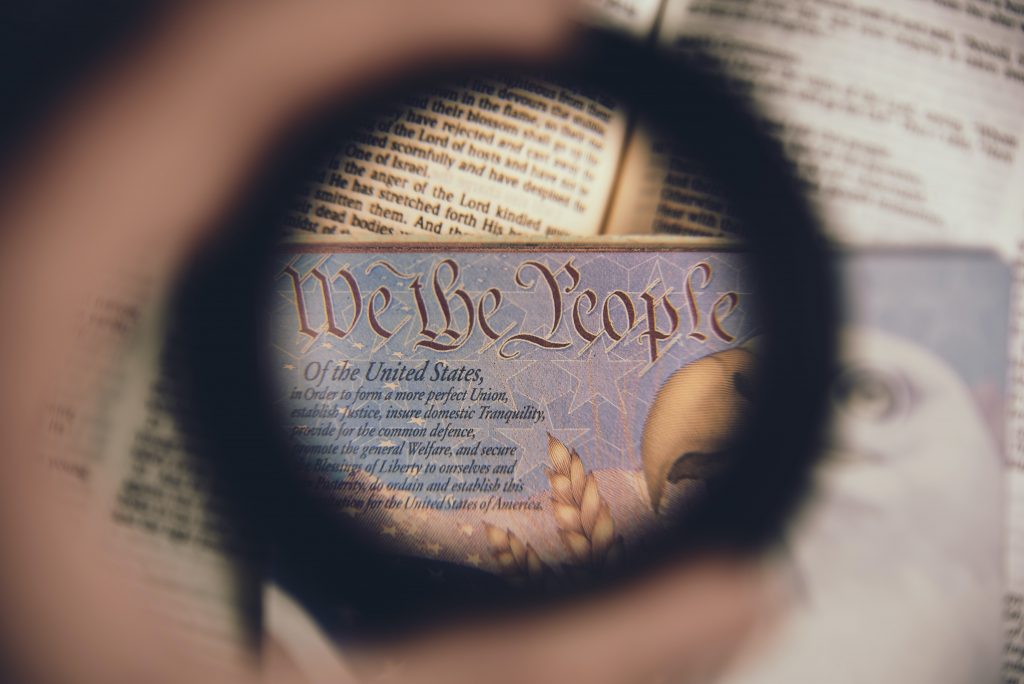

The latter are fundamental elements of institutions as they influence formal rules. In a seminal contribution to institutional economics, North (1994) distinguishes between two forms of institutions: formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights etc.) and informal constraints (norms of behaviour, conventions, self-imposed codes of conduct etc.). In a later work, he argued that institutions evolve incrementally and successively over time (North, 1991). When those two forms are approached as two separated sources of institutions, the role of informal constraints in institutional evolution will be missed, throwing a veil over a core aspect of institutions and leading us to fallacious conclusions about the key determinants of growth and development.

Similarly, Karl Popper (1945) distinguishes an open society from a closed society based on whether a distinction exists between normative laws and natural laws. Where there is none – what Popper calls a closed “tribal society”– taboos and conventions act as if they were natural law. This gives them a powerful role in society and a fundamental role in development. By creating formal laws, societies recognise the distinction between norms and natural laws, weakening the effect of conventions (although, as we will see, they still act through both formal and informal laws).

Both North and Popper agree on this chronological development of institutions meaning a better understanding of causation is needed. Myrdal (1978) convincingly argues that the mechanisms of social systems are determined by an endogenous cycle of causation that affects the distribution of power in a society and economic, social and political stratification). This means that a change in informal constraints will alter formal rules, which will then return to affect the former. Therefore the scaffolding of institutions consists of norms of behaviour, conventions and self-imposed codes of conduct.

The revolutionary crevasse

Just as a crevasse provides a glimpse deep into the ice, revolutions open a window to the creation and destruction of social systems. Revolutions are beloved by social scientists (especially in institutional economics) as they provide natural experiments to investigate causal effects. They can shed some light on the importance of norms and convention, as well as their relationship with ideas, ideologies and leaders.

In the literature, for example, Acemoglu et al. (2008) and North & Weingast (1989) have respectively examined the impact of the French Revolution on development and the Glorious Revolution on institutional structure. However, these types of studies have focused only on the secondary changes (in laws and property rights) instead of the initial causes of change (norms and conventions). In this regard, a re-evaluation of revolutions and their characteristics is necessary to observe the initial changes.

Let us first consider which elements prepare amenable conditions for the emergence of revolutions. Gottschalk (1944) identifies three broad factors:

- demand for change stemming from (a) personal discontent and (b) social dissatisfaction

- hopefulness derived from (a) popular programs of reform and (b) a leader

- weakness of the conservative forces – perhaps the most important.

Demand comes from widespread provocations (corruption, taxation, poor infrastructure etc.) which generate social dissatisfaction. Yet, demand by itself is not sufficient for the revolution. Some hope of success is also needed. This comes from programs of reform, as provided by the Voltaires and Rousseaus, the Lockes and Ademses, and the Marxes and Kropotkins (Gottschalk, 1994). However, tuneless emphasis on widespread provocations that are based on the formal rules underestimates the phycological mechanisms that are mainly based on informal constraints.

Personal discontent (arising for idiosyncratic reasons) only appears at the individual level yet plays an essential role in generating the leaders of revolutions. These leaders then support the new-born ideas and ideologies based on the program of reform which has a multiplier effect by coherently spreading revolutionary sentiment. This is crucial once we think of revolutions as risky events over which individuals have varying valuations of the possible outcomes. Gneezy et al. (2006) show that individuals, faced with a complex choice, may choose to stay in the old system if they value the risky benefits of revolution less than the worst outcomes of rebelling. However, once the revolutionary “lottery” is based on intellectuals’ programs of reforms and explained by leaders it becomes easier to code.

In this way, agents facing complex task (in this case revolution), might act following the leader through many of the channels identified by behavioural economics such as Tversky and Kahneman’s simple heuristics, Walker and Wooldridge’s conventions and Shiller’s narratives. These share common features which affect the majority’s decision-making processes – especially when tasks are complex.

This process is essential to notice the importance of informal constraints and how they become formal rules since leaders are the symbol of ideologies and ideas. As Axelrod indicates norms precede laws and laws strengthen norms. After the success of the revolution laws strengthen the norms through formalization. And after social conventions are entrenched, they become thoughtlessly accepted by individuals (Epstein, 2001).

As with the example of revolutions, before a change in the formal rules, an ideological revolution has occurred when intellectuals provide the programs of reforms. The ideas become conventions during the revolution, changing societal expectations. Notions of equality and liberty – in the case of the French Revolution – became the convention as the system was upended. The relationships between ideas, ideologies, norms and leaders encourage us to take them into account when evaluating growth and development.

Conclusion

I have argued that ideas, norms and ideologies are the initial drivers of development and have had an immense effect on our civilizations. However, traditional political economy’s overemphasis of formal rules fails to capture this. The insularity of this approach is highlighted by examining Revolutions, which provide evidence in favour of more inclusive definitions of institutions and the importance of ideas, ideologies and leaders in creating social systems. Therefore, I contend that a more holistic approach to analysing development is required otherwise alternative and ill-founded explanations of growth with remain.

References

Acemoglu, D., Cantoni, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2008). From ancien regime to capitalism: the French Revolution as a natural experiment. Natural Experiments…, op. cit, 221-256.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, institutional change, and economic growth. American Economic Review, 95(3), 546-579.

Ashraf, Q., & Galor, O. (2013). The ‘Out of Africa’ hypothesis, human genetic diversity, and comparative economic development. American Economic Review, 103(1), 1-46.

Axelrod, R. (1986). An evolutionary approach to norms. The American Political Science Review, 1095-1111.

De Long, J. B., & Shleifer, A. (1993). Princes and merchants: European city growth before the industrial revolution. The Journal of Law and Economics, 36(2), 671-702.

Epstein, J. M. (2001). Learning to be thoughtless: Social norms and individual computation. Computational economics, 18(1), 9-24.

North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97-112.

North, D. C. (1994). Economic performance through time. The American Economic Review, 84(3), 359-368.

North, D. C., & Weingast, B. R. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: the evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. The Journal of Economic History, 49(4), 803-832.

Popper, K. R. (1945). The open society and its enemies. Routledge, London.

Myrdal, G. (1978). Institutional economics. Journal of Economic Issues, 12(4), 771-783.

Gottschalk, L. (1944). Causes of revolution. American Journal of Sociology, 50(1), 1-8.

Connect with the author

Oguz Kortut Keles ’20 is an alum of the Barcelona GSE Master’s in Economics.

This post was edited by Ashok Manandhar ’21 (Economics).

Marco Antonielli ’12 (International Trade, Finance, and Development) is a consultant with Nathan Associates in London. Prior to this he was a consultant at the OECD in Paris and a research assistant at the Bruegel think tank in Brussels. The following piece by Marco originally appeared on Nathan’s website. (All opinion and analysis are only those of the author.)

Marco Antonielli ’12 (International Trade, Finance, and Development) is a consultant with Nathan Associates in London. Prior to this he was a consultant at the OECD in Paris and a research assistant at the Bruegel think tank in Brussels. The following piece by Marco originally appeared on Nathan’s website. (All opinion and analysis are only those of the author.)