Post by Ana Costa Ramón ’14 and Ana Rodríguez-González ’14 (Economics Program). Both are PhD candidates of GPEFM (UPF and Barcelona GSE).

Update 17.07.2019: The authors received the second place Student Paper Prize for this research at the International Health Economics Association (iHEA) 2019 Congress in Basel, Switzerland!

Update 29.01.2019: This research has been nominated for the “Vanguardia de la Ciencia” awards promoted by La Vanguardia newspaper and the Catalunya-La Pedrera Foundation!

In recent decades there has been an increasing concern about the rise of cesarean section births. Among OECD countries in 2013, on average more than 1 out of 4 births involved a c-section (OECD, 2013), being one of the most commonly performed surgeries. Cesarean sections, performed when needed and under standard quality measures, save lives. However, unnecessary c-sections not only impose significant costs for the health system but can also negatively impact infant health. Previous literature has found cesarean sections to be associated with several adverse health outcomes for the newborn (Grivell & Dodd, 2011) and with worse later infant health(Keag, Norman, & Stock, 2018). However, most of the studies that came to these conclusions compared mothers who gave birth vaginally with those that had a cesarean section, and this may produce biased results: mothers who give birth by c-section are likely to have different characteristics from those who have vaginal births, and this may influence the health outcomes of the child and the mother after delivery.

In a recent paper, published in the Journal of Health Economics (Costa-Ramón, Rodríguez-González, Serra-Burriel, & Campillo-Artero, 2018), we contribute to fill this gap by providing causal evidence of the impact of avoidable cesarean birth on neonatal health. To do so, we exploit variation in the probability of having a c-section that is unrelated to maternal characteristics: variation by time of day.

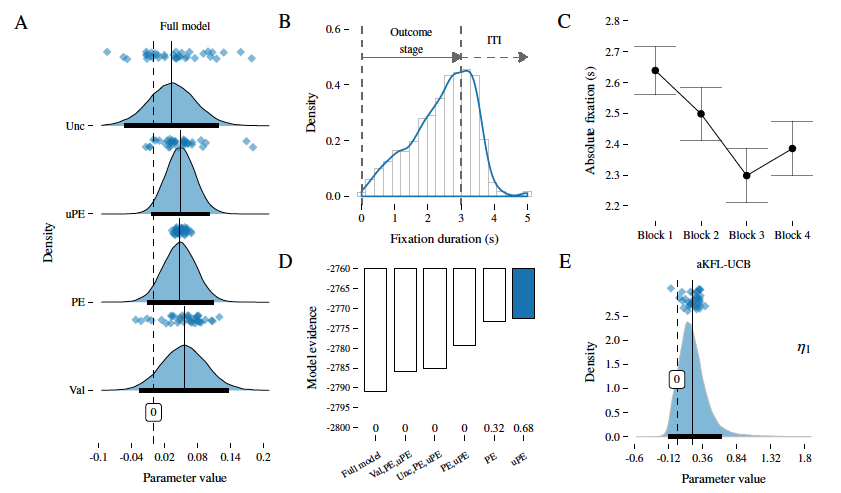

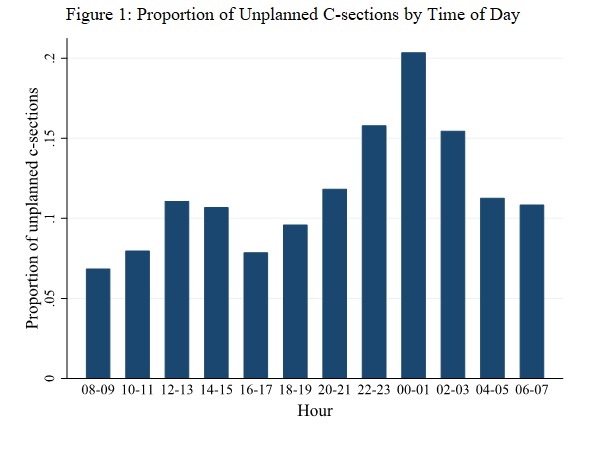

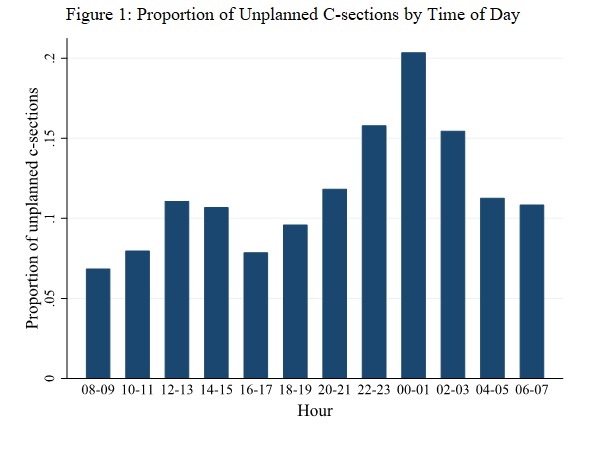

In particular, using data from four public hospitals in Spain, we first document that the probability of having an unplanned c-section is higher in the early hours of the night (from 11 pm to 4 am) and that this is not driven by different characteristics of mothers giving birth during these times. Figure 1 shows the c-section rate at different times of day in our sample. We can observe that the distribution of unscheduled c-sections by time of birth is not uniform. Births that take place between 11 pm and 4 am are around 6 percentage points more likely to be by cesarean.

Notes: The figure represents the proportion of unplanned c-sections by time of day over the sample of unplanned c-sections and vaginal births. Sample is restricted to single births, unscheduled c-sections and vaginal births (excluding breech vaginal babies).

We argue that, given the medical shift structure in public hospitals and the larger time-cost of surveillance implied by vaginal deliveries, doctors’ incentives to perform c-sections in ambiguous cases may be higher during these times. In fact, we are not the first to document peaks in the unplanned c-section rate during the early night. Previous studies interpret this variation as evidence that convenience and doctors’ demand for leisure influence timing and mode of delivery (Brown, 1996; Fraser et al., 1987; Hueston, McClaflin, & Claire, 1996; Spetz, Smith, & Ennis, 2001).

We take advantage of this exogenous variation and use time of day as an instrument for the probability of having an unplanned c-section. This allows us to compare mothers that give birth in the same hospital and have similar observable characteristics, differing only in the time of delivery. Our results suggest that these non-medically indicated c-sections lead to a significant worsening of Apgar scores of approximately one standard deviation, but we do not find effects on more extreme outcomes such as needing reanimation, being admitted to the ICU or on neonatal death. This is an important finding, given that previous studies in the medical literature documented an association between c-sections and an increased risk of serious respiratory morbidity and subsequent admission to neonatal ICU (Grivell & Dodd, 2011). Their findings are consistent with the results of our OLS estimation, suggesting that former analysis might have been capturing the underlying health status of newborns who need a medically necessary cesarean.

A few words on the publication process and media coverage

Given that it was a health-oriented paper, we decided to target a top field journal in health economics. We were very lucky and all the publication process went very fast and smoothly. We had to revise the paper once and get additional data in order to be able to address some of the reviewers’ comments.

When it was published, with the help of UPF’s communication unit we sent a press release and our paper got attention from the Spanish media. We knew that it was a controversial topic (especially from the doctors’ perspective) so we chose our words carefully, but still we got some slightly sensationalist headlines. We learnt the lesson: you have to choose a catchy punchline yourself, or they will pick their own (and you won’t always like it).

Overall, it has been an intense and fruitful experience!

References:

Brown, H. S. (1996). Physician demand for leisure: Implications for cesarean section rates. Journal of Health Economics, 15(2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6296(95)00039-9

Costa-Ramón, A. M., Rodríguez-González, A., Serra-Burriel, M., & Campillo-Artero, C. (2018). It’s about time: Cesarean sections and neonatal health. Journal of Health Economics, 59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.03.004

Fraser, W., Usher, R. H., McLean, F. H., Bossenberry, C., Thomson, M. E., Kramer, M. S., … Power, H. (1987). Temporal variation in rates of cesarean section for dystocia: Does “convenience” play a role? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 156(2), 300–304. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(87)90272-9

Grivell, R. M., & Dodd, J. M. (2011). Short- and long-term outcomes of cesarean section. Expert Review of Obsetrics and Gynecology, 6(2), 205–216.

Hueston, W. J., McClaflin, R. R., & Claire, E. (1996). {V}ariations in cesarean delivery for fetal distress. The Journal of Family Practice, 43(5), 461–467.

Keag, O. E., Norman, J. E., & Stock, S. J. (2018). Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 15(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002494

OECD. (2013). Health at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Spetz, J., Smith, M. W., & Ennis, S. F. (2001). Physician Incentives and the Timing of Cesarean Sections: Evidence from California Physician Incentives and the Timing of Cesarean Sections Evidence From California. Source: Medical Care MEDICAL CARE, 39(6), 536–550. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200106000-00003