At the welcome event for new students on September 26, alum Marc de la Barrera ’17 shared some advice from his recent experience as a student in the Barcelona GSE Economics Program.

Here is the text of his speech (see if you can spot all the references to a certain television series…)

Dear BGSE students, staff, professors and friends,

I am very happy to be here giving this speech, remembering myself just one year ago sitting in your place. By that time I was an engineer starting an Economics Master, both amused but nervous for digging in a new field. “You know nothing, Marc Barrera”, I keept saying to myself. One year later, at least I can say I know something.

In the Economics Master, I learnt to play with macroeconomic models, how to gather valuable information from data, and to understand how we take decisions. Also that asking the right question is almost as important as finding the answer. I remember me having troubles understanding the “risk free rate” concept. How is it possible that you get a return on your money for sure? Then someone told me that America always pays its debts. Well, they assume they do, I don’t know if now they are so confident with its new administration. Those in data science will learn that information is power, while these of you taking political economy classes will argue that power is power. For competition ones… well, competition is lack of power. And no matter which master you are enrolled in, you are going to meet, John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, Companion of the Order of the Bath, Fellow of the British Academy and father of modern economics.

I hope you are enjoying your time here, nice weather, meeting new people every day, no pressure… But summer will not last forever. Soon you will realize that winter is coming, and with them, exams. And remember that when exams come and problem sets appear, the lone student dies but the pack survives. Everyone has its studying style, but I deeply encourage you form teams and work altogether. You are here, hence you are all very intelligent, I have no doubt about that, but there is a problem… Your professors more. You will need to merge several minds to solve one problem. You have different backgrounds, someone will be very strong in formal math, others might excel at economic intuition, and others will know coding. These three aspects, and many others, are needed to succed all the masters at BGSE.

But it is not only what I learnt that made last year special, it was the experiences I lived and more importantly, the people I meet. I want to make use of this privilaged attention I have, to encourage BGSE to do more activities outside the academic environment, at the same time that I congratulate them for the ones they are currently performing. Butifarrada, football tournamen, sky trip, fideuà… Go to as many events as you can, if not all. Defying all economic laws, this events provide one thing that economists belief do not exist: “free lunch” (just ignore the tuition fees).

Then the people. You will get in touch with many people from many nationalities, such opportunity must be taken. But is not only the cultural exchange what matters. Feelings, frienship will arise. Some cuples will form with probability one. Networking to get opportunities, information or new jobs is fine, but spending time with people you like and appreciate, is better.

>And finally the faculty. Their level is extraordinary, make the most of them. Not only during the class, they are here to help and guide you. I might have abused of their kindness last year, but every professor and staff member I asked to see, whether for a technical doubt regarding the notes, to more fundamental and vital questions like “should I do a PhD”, received me and helped me as much as they could. Luckily you don’t have to send a raven, although we have more pidgeons here, an e-mail should work. The objective of the faculty is to make the most of you, so let them help.

Whether you stay in Bellaterra at UAB or in the Citadel Campus at UPF, it is time to go beyond the wall. After the master the research frontier will be near, and some of you, like me, will opt to go further, to the unexplored. Those who opt for a professional career, maybe we will make it to the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Congratulations for being admitted to your program. This year will be a great year: you will learn economics, meet people, and discover cultures. I hope that the first weeks have been pleasant, and get ready to work hard, because as bodybuilders say, “no pain, no gain”.

Original post and more from Marc de la Barrera on his personal blog. Connect with Marc on Twitter and LinkedIn

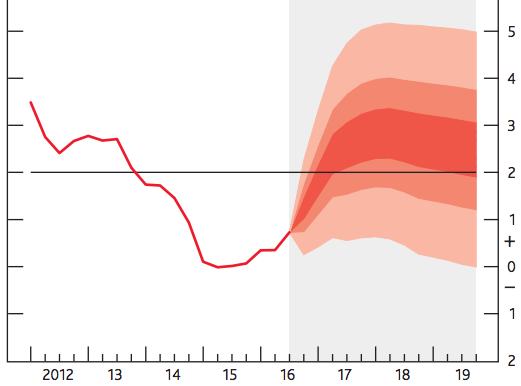

Editor’s note: In this post, Greg Ganics (Economics ’12 and PhD candidate at UPF-GPEFM) provides a non-technical summary of his job market paper, “Optimal density forecast combinations,” which has won the

Editor’s note: In this post, Greg Ganics (Economics ’12 and PhD candidate at UPF-GPEFM) provides a non-technical summary of his job market paper, “Optimal density forecast combinations,” which has won the

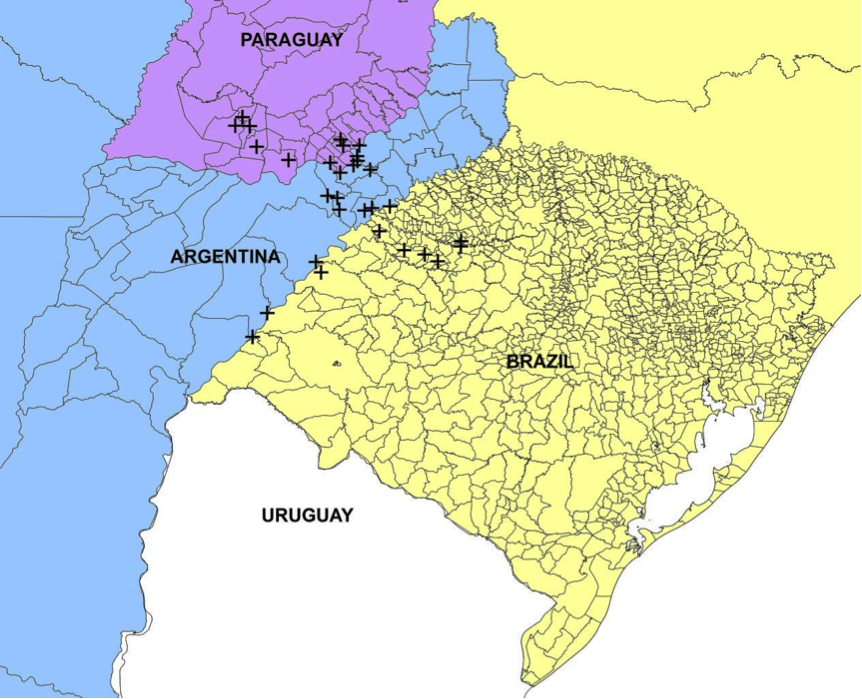

The following job market paper summary was contributed by

The following job market paper summary was contributed by

The following job market paper summary was contributed by

The following job market paper summary was contributed by