Editor’s note: this article was originaly published in Spanish in the popular economics blog, Nada es Gratis, and is based on Miriam Artiles’s PhD from Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Her Job Market Paper was honorably mentioned in the third annual Nada es Gratis Job Market Paper awards.

Is ethnic diversity good or bad for economic development? When different languages, ethnicities or races coexist in the same society, there are challenges for the economy, but also opportunities. On one hand, if individuals within ethnic groups are homogeneous, and groups differ in preferences toward policies or public goods, then conflicting preferences can lead to inefficiencies in public good provision or to policy choices that may not benefit the entire society. Inter-group tensions can also result in civil conflicts or exacerbate mistrust and lack of cooperation. However, on the other hand, if ethnic groups differ in subsistence activities or skills, then complementary specializations can generate economic gains, stimulate innovation, and promote inter-group trade. Alesina and La Ferrara (2005) provide a review of this literature. While there is a general understanding that diversity brings opportunities and challenges, there is scarce evidence on which factors determine its positive or negative consequences. When is ethnic diversity good for economic development, and when is it bad?

I ask whether the effect of ethnic diversity on economic development depends on one characteristic of ethnic groups that has received little attention: the heterogeneity of individuals within ethnic groups. Underlying previous literature is the assumption that individuals within ethnic groups tend to be homogeneous. However, individuals may differ in many dimensions, including preferences, economic activities or skills, as well as cultural, genetic, and linguistic traits. I focus on having different economic specializations and skills within the same ethnic group, and I study whether ethnic groups with more heterogeneous individuals do better in multi-ethnic societies.

Consider two ethnic groups, A and B. The two groups differ in ethnicity. In turn, ethnic group A has individuals with diverse skills due to their different economic specializations, while ethnic group B is more homogeneous (individuals from ethnic group B have similar skills). The idea is that it may be easier for individuals of ethnicity A to live and to interact in a multi-ethnic society–they come from an ethnic group that is already highly heterogeneous. They will already be used to diverse environments. They will be more familiar with having to interact with heterogeneous individuals. If you come from an ethnic group that is highly heterogeneous, in terms of skills, you may be more willing to live and to interact with other ethnicities. In this case, positive interactions, mutually beneficial exchange, between ethnic groups will become more frequent.

The 16th Century resettlement of Peruvian ethnic groups

To study this, I collect new data on a natural experiment from Peru’s colonial history. I focus on highland Peru. There, Spanish colonizers resettled native populations in the 16th century. They forced together different ethnic groups in new villages, and this happened unintentionally. Importantly, in some ethnic groups, individuals had already been living in very different ecological zones of the Andes, at different altitudes, during the pre-colonial period, before the Spanish conquest. This creates within-group heterogeneity. In some cases, individuals from the same ethnic group were very different in terms of ecological specializations and skills – the types of lands and crops that they were used to cultivate. In other ethnic groups, everyone lived in the same climate zone, at the same altitude. I am asking: did the more heterogeneous ethnic groups do better once they were resettled in multi-ethnic villages?

Firstly, I use a map of the spatial distribution of ethnic groups at the time of the Spanish conquest. It allows me to compute the distance from each village to the closest ethnic frontier and use it as a source of quasi-random variation in ethnic diversity. During the pre-colonial period, individuals from the same ethnic group were distributed vertically, at different altitudes. This is the thesis of the anthropologist John Murra. He documents this vertical settlement pattern as a subsistence strategy in an environment in which differences in elevation create a variety of ecological zones and climates. At the time of the resettlement, the mountain environment of the Andes was new to Spanish colonizers – they were used to a flatter world. As a result, in villages that were created close to ethnic borders, they concentrated individuals from different ethnicities unintentionally (Pease 1978; Wachtel 1976). Secondly, I use spatial data on the distribution of ecological zones to compute a proxy for the heterogeneity of skills within each ethnic group prior to the conquest. It is important to note that ethnic groups with more heterogeneous skills may be different in other dimensions (e.g., group size, population density, etc). In the analysis, I use all the available data on the pre-colonial characteristics of ethnic groups to account for the main correlates of within-group heterogeneity.

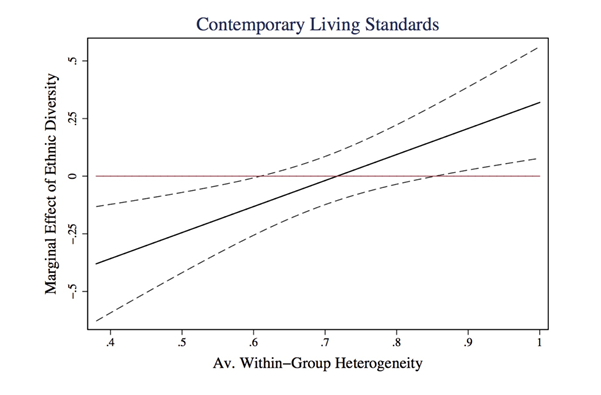

The first result in the paper documents the direct effect of ethnic diversity, which I benchmark against previous results in the literature. I find that ethnic diversity is robustly associated with lower living standards in the long run. Specifically, I explore a variety of outcomes that capture contemporary living standards. As proxies for local economic activity, I use light intensity per capita (2000-2003) and a measure of non-subsistence agriculture from the agricultural census of 1994. For access to public infrastructure, I use data from the 1993 population census on access to public sanitation and the public network of water supply. This result is in line with the literature on the costs of ethnic diversity, though it also highlights the persistent consequences of forced diversity at the local level. When examining the effect of ethnic diversity and within-group heterogeneity, I find the following pattern:

The figure shows the average effect size of ethnic diversity as a function of within-group heterogeneity. I find a robust pattern: the more heterogeneous an ethnic group was prior to resettlement, the lower the cost of ethnic diversity. On average, where ethnic groups have more heterogeneous individuals in terms of skills, the negative effect of ethnic diversity is reduced, and ethnic diversity may even become an advantage for economic development. To understand the evolution of these long-term effects, I use data from the 1876 population census on occupations and literacy rates, showing that the documented pattern persists over time.

Why is this happening? When exploring potential channels, I find evidence consistent with cultural transmission. Individuals from more heterogeneous ethnic groups in terms of skills are more likely to interact with other ethnicities. Using data from colonial records, I find evidence suggesting cooperative behavior and more open attitudes when interacting with other ethnic groups. Overall, understanding whether individuals from more heterogeneous ethnic groups are better able to integrate in a multi-ethnic society is a relevant question, not only in an increasingly globalized world, but also in the context of forced displacements and migrations, like in the case of refugees.

References

Alesina, A., and La Ferrara, E. (2005). “Ethnic Diversity and Economic Performance.” Journal of Economic Literature, 43 (3), pp. 762-800.

Murra, J. V. (1975). Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

Pease, F. G. Y. (1978). Del Tawantinsuyu a la historia del Perú, Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

Wachtel, N. (1976). Los vencidos: los indios del Perú frente a la conquista española (1530-1570). Alianza.

Connect with the author

Miriam Artiles ’15 is a PhD candidate in Economics at Universitat Pompeu Fabra and will soon start as an Assistant Professor at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. She is an alum of the Barcelona GSE Master’s in Economics.

This post was edited by Ashok Manandhar ’21 (Economics).