This post is based on the article Ayudas a la dependencia y uso de los servicios sanitarios, ¿qué nos dicen los datos administrativos? (Nada Es Gratis, April 2021) by Helena Hernández-Pizarro, Guillem López Casasnovas, Catia Nicodemo, and Manuel Serrano Alarcón.

Since the 2007 implementation of the “Dependency Act”, people with functional limitations in Spain can request Long-Term Care (LTC) benefits. The Act’s main objective is to improve the care and quality of life of people who have lost their autonomy. Fourteen years later, evidence on the impact of the Dependency Act in Spain on its beneficiaries remains scarce. This is partly because we need data on the quality of life of this population in order to fully evaluate its impact and we still don’t gather a suitable indicator. However, we can assess the impact of benefits by utilising data on the use of healthcare services as a proxy to estimate quality of life and health, and that is the approach we have taken in our research.

The relationship between LTC benefits and healthcare use

The effect of LTC benefits on healthcare use is not trivial and may have implications not just for the quality of life of recipients, but also for the management of healthcare services.

If access to LTC improves the health status of dependent people (for example through better treatment management, better nutrition or avoiding domestic accidents), investments in the LTC system could save healthcare providers money in the future. On the other hand, LTC benefits might increase the demand for healthcare, for example through greater health-monitoring by caregivers.

Using data on the type of healthcare service, type of admission and diagnoses, we can better understand the relationship between benefits and healthcare use, and therefore increase the efficiency in the allocation of social care and healthcare resources to design a better integrated care system.

The data

To study the effects of LTC benefits on healthcare use, we needed to gain access to data from social services and healthcare providers and then link it. As others have shown, this was not easy, but fortunately, the interest of the institutions involved in this research —CatSalut, AQuAS, the Departament de Treball, Afers socials i Famílies de la Generalitat de Catalunya (DTASF) (Labour, Family and Social services department) and CRES (UPF) — helped to facilitate this process.

Even with access to the data, measuring the effect of LTC benefits on the health system is not straightforward. Those who qualify for benefits will by definition have worse health and, regardless of the new policy, will probably make greater use of the healthcare system than those who don’t qualify for benefits. Therefore, simply comparing those applicants who receive LTC benefits with those who don’t would not help us to identify the effects of the Dependency Act.

To deal with this, we use an instrumental variable technique based on the “leniency” of the evaluators. The idea is as follows. When there is an evaluation guided by objective criteria such as when grading an exam, imposing a judicial sentence or assigning the severity of a medical case, there is always a degree of subjectivity from the person performing the assessment. It is common in research literature to consider this as a source of exogenous variation, because there is no predictable basis by which assessors should differ. This allows us to use traditional statistical methods that can identify any consequences associated with new policies. In our context, despite the fact that the assessment is based on the Dependency Assessment Scale, each examiner has a small margin of subjective interpretation. Thus, there are examiners who, on average, tend to provide slightly higher scores, so that their applicants qualify for greater LTC benefits. Since the applicant cannot choose his/her examiner, being assessed by one examiner or another affects the probability of receiving a benefit which is exogenous to the assessment process.

The results

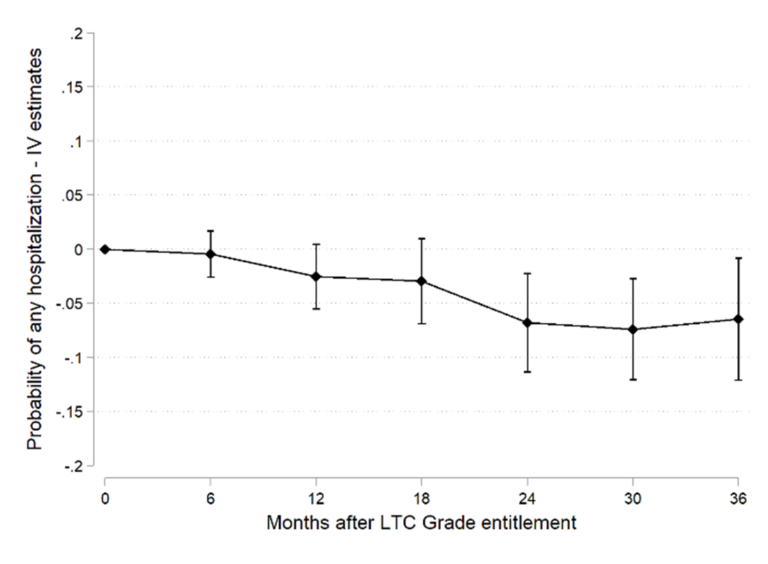

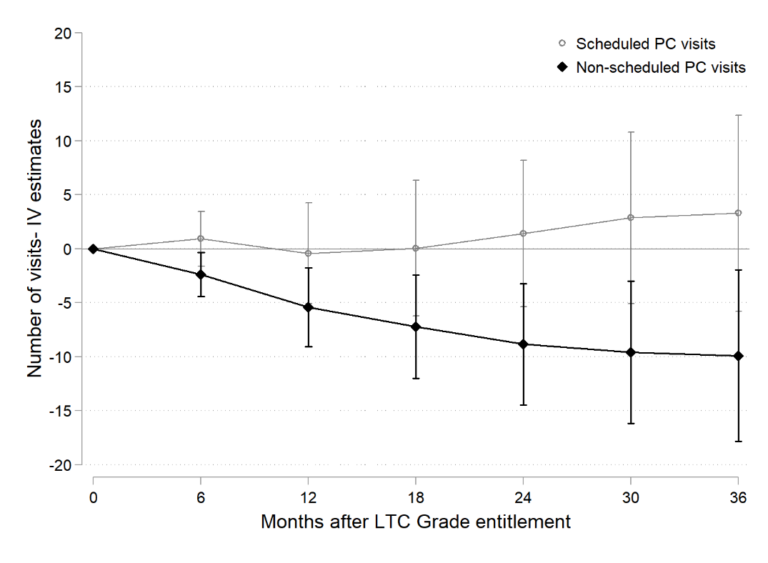

In the two graphs below, we summarize the most important results from our research.

Figure 1 shows that access to LTC benefits decreases by 7 percentage points the probability of a group of hospitalizations considered by the medical literature as avoidable with continuous care for the elderly (such as hospitalizations for injuries, ulcers and nutritional deficiencies). This represents a 60% reduction in this type of hospitalization.

Figure 2 shows that unscheduled visits to primary care decrease by almost 10 visits two years after receiving LTC benefits, a 50% reduction with respect to the mean. Our analysis by diagnosis indicates that this reduction is explained by a sharp drop in visits caused by the economic and family situation of the individual.

Conclusions

Our results show that LTC benefits can mitigate the use of healthcare services, in line with the conclusions of previous research. Additionally, our data allows us to go one step further, identifying in detail the types of services which are the most affected.

Particularly interesting are the results relating to primary care, where LTC benefits strongly reduce visits not strictly related to health causes. It seems that reinforcing the LTC system will not only improve the quality of life of dependents and caregivers, but may also reduce the pressure on the healthcare system.

Undoubtedly, these results are important given the chronic under-financing of the LTC system, especially in a context where COVID-19 has highlighted a need for real integration between social and health care. This is just one example of how access to, and analysis of administrative data can contribute to the evaluation of public policies, facilitating better informed decision making.

Connect with Barcelona GSE Alumni

Helena Hernández-Pizarro (ECON ’11, HEP ’12, GPEFM ’17) is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Research in Health and Economics (CRES-UPF).