Evaluating the performance of merger simulation using different demand systems: Evidence from the Argentinian beer market

Editor’s note: This post is part of a series showcasing BSE master projects. The project is a required component of all Master’s programs at the Barcelona School of Economics.

Abstract

This research arises in a context of strong debate on the effectiveness of merger control and how competition authorities assess the potential anticompetitive effects of mergers. In order to contribute to the discussion, we apply merger simulation –the most sophisticated and often used tool to assess unilateral effects– to predict the post-merger prices of the AB InBev / SAB-Miller merger in Argentina.

The basic idea of merger simulation is to simulate post-merger equilibrium from estimated structural parameters of the demand and supply equations. Assuming that firms compete a la Bertrand, we use different discrete choice demand systems –Logit, Nested Logit and Random Coefficients Logit models– in order to test how sensible the predictions are to changes in demand specification. Then, to get a measure of the precision of the method we compare these predictions with actual post-merger prices.

Finally, to conclude, we point out the importance of post-merger evaluation of merger simulation methods applied in complex cases, as well as the advantages and limitations of using these type of demand models.

Conclusion

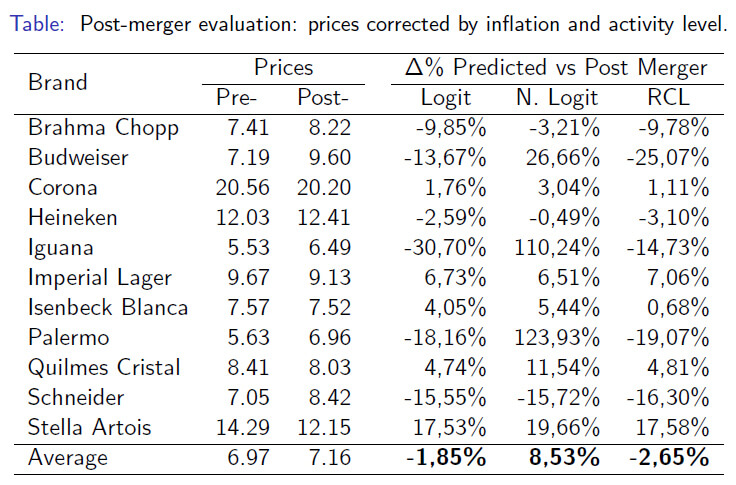

Merger simulations yield mixed conclusions on the use of different demand models. The Logit model is ex-ante considered inappropriate because of its restrictive pattern of substitution, however it performed better than expected. Its predictions on average were close to the predictions of the Random Coefficients Logit model, which should yield the most realistic and precise estimates. Conversely, the Nested Logit model largely overestimated the post-merger prices. However, the poor performance is mainly motivated by the nests configuration: the swap of brands generates almost two close to monopoly positions in the standard and low-end segment for AB InBev and CCU, respectively. This issue, added to the high correlation of preferences for products in the same nest, generates enhanced price effects.

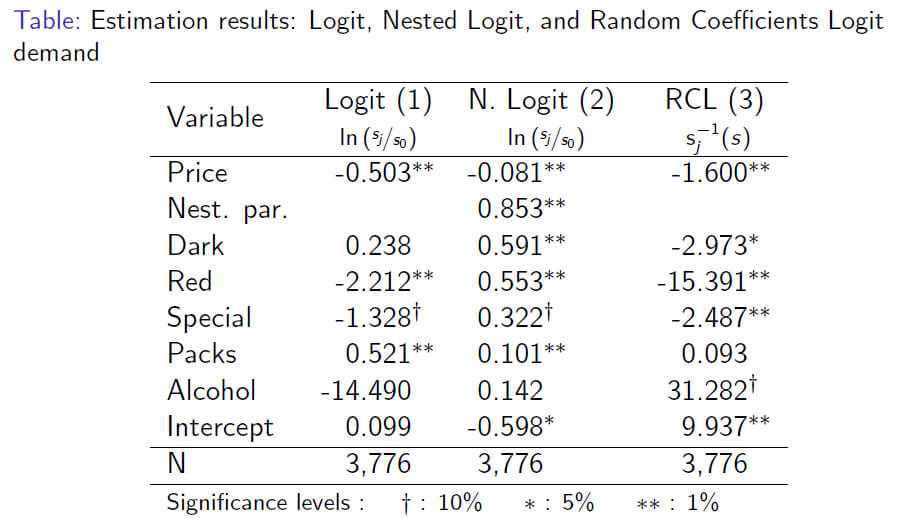

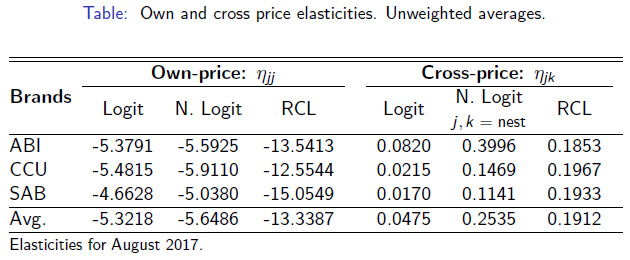

Regarding the substitution patterns, the Logit, Nested Logit and Random Coefficients Logit models yielded different results. The own-price elasticities are similar for the Logit and Nested Logit model, however for the Random Coefficients Logit model they are more almost tripled. This is likely driven by the estimated larger price coefficient as well as the standard deviations of the product characteristics. As expected, by construction the Random Coefficients Logit model yielded the most realistic cross-price elasticities.

Our question on how does the different discrete choice demand models affects merger simulation –and, by extension, their policy implications– is hard to be answered. For the AB InBev / SAB-Miller merger the Logit and Random Coefficients Logit model predict almost zero changes in prices. Conversely, according to the Nested Logit, both scenarios were equally harmful to consumers in terms of their unilateral effects. However, as mentioned above, given the particular post-merger nests configuration, evaluating this model solely by the precision of its predictions might be misleading. We cannot discard to have better predictions under different conditions.

As a concluding remark, we must acknowledge the virtues and limitations of merger simulation. Merger simulation is a useful tool for competition policy as it gives us the possibility to analyze different types of hypothetical scenarios –like approving the merger, or imposing conditions or directly blocking the operation–. However, we must take into account that it is still a static analysis framework. By focusing only on the current pre-merger market information, merger simulation does not consider dynamic factors such as product repositioning, entry and exit, or other external shocks.

Authors: Leandro Benítez and Ádám Torda

About the BSE Master’s Program in Competition and Market Regulation