In this paper, we study the sectoral reallocation of employment due to automation in Germany. Empirical evidence by Dauth et al. (2021) shows that robot adoption has induced a shift of employment from the manufacturing to the service sector, leaving total employment unaffected. We rationalize this evidence through the lens of a two-sector, general equilibrium model with matching frictions and endogenous participation.

Few papers have studied the effect of automation on employment in a multi-sectoral model. Berg et al. (2018) argue that the inclusion of a non-automatable sector amplifies the difference between the effect of automation on low- and high-skill workers. Sachs et al. (2019) also include a non-automatable sector in an overlapping generations model. They study the possibility of one generation improving their welfare at future generations’ expense through robot adoption. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to build a two-sector general equilibrium model with search and matching frictions to analyze the long-run impact of automation on both sectoral and aggregate employment.

We consider a representative household that decides how to allocate its members between non-participants in the labor markets, job-searchers in manufacturing, and job-searchers in services. The household also accumulates capital. On the production side, there is a representative firm in each sector. The manufacturing firm decides how many vacancies to post and how much capital to borrow from the household. Automation increases the capital intensity of the technology in the manufacturing sector. This can be motivated by the idea that some work operations, formerly performed by humans, are now executed by robots (Acemoglu and Restrepo (2018)). In the service sector, we assume for simplicity that no capital is needed, and thus the representative firm decides only the number of vacancies to post.

Key takeaways

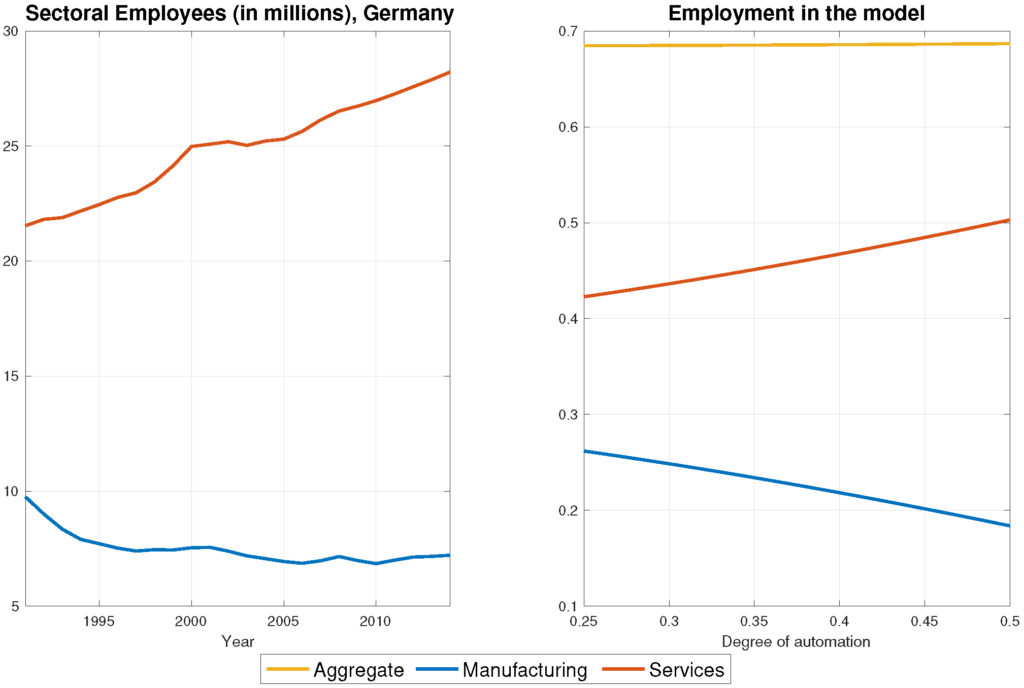

After calibrating our model to the German economy in 1994, we perform steady-state comparative statics to study the long-run impact of automation on sectoral reallocation of employment. As the stock of robots increased by 87% in Germany between 1994 to 2014, we can qualitatively compare the model economy’s reaction to an increase in the degree of automation with the sectoral employment shares we observe in Germany over time.

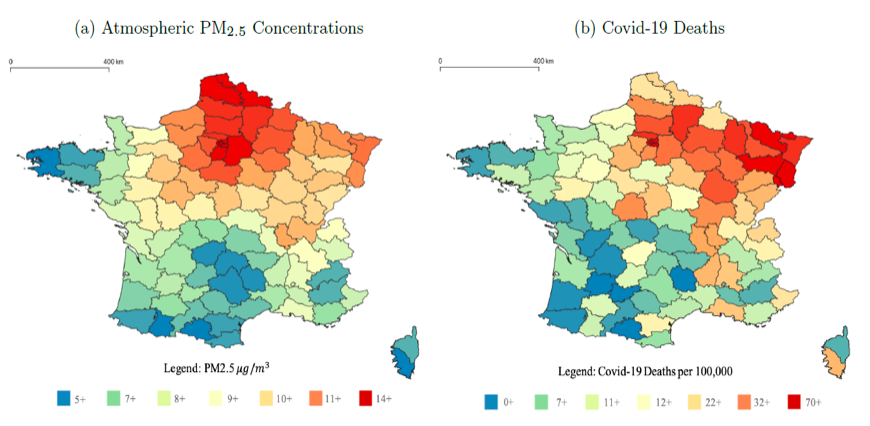

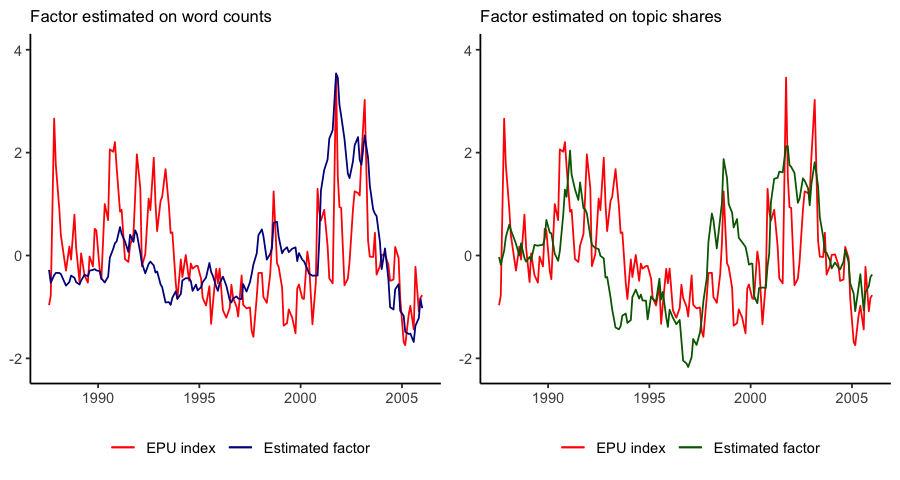

The right panel of Figure 1 shows the model implied values of sectoral employment levels together with total employment. A higher degree of automation, which we take as a proxy of robot adoption, increases employment in services and decreases it in manufacturing. Despite the adjustments of sectoral employment, total employment remains constant, consistently with the empirical evidence of Dauth et al. (2021). In the left panel of Figure 1, we plot the employment shares in the German economy, which we compute using data from the German Federal Statistical Office (DESTATIS). The model qualitatively replicates the observed pattern in sectoral employment.

To assess how well our model can explain the sectoral reallocation of employment in Germany, we focus on comparing two steady states. These two steady states correspond to the start and end years in the empirical analysis of Dauth et al. (2021). The model predicts a decline of 27% in the ratio of manufacturing employment to service employment, which is reasonably close to the one found in the aggregate data for the German economy, i.e., 32%.

Having shown that the model replicates the sectoral reallocation we observe in the data, we then ask the following question. What determines the extent of sectoral reallocation?

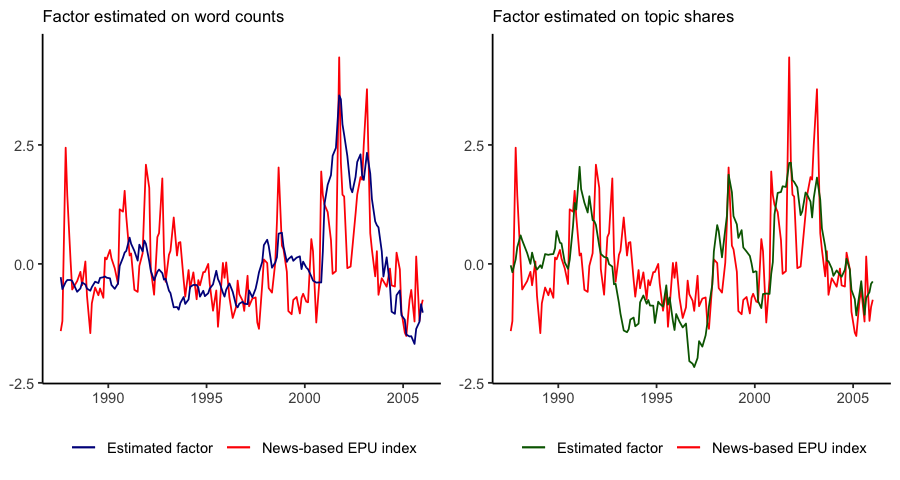

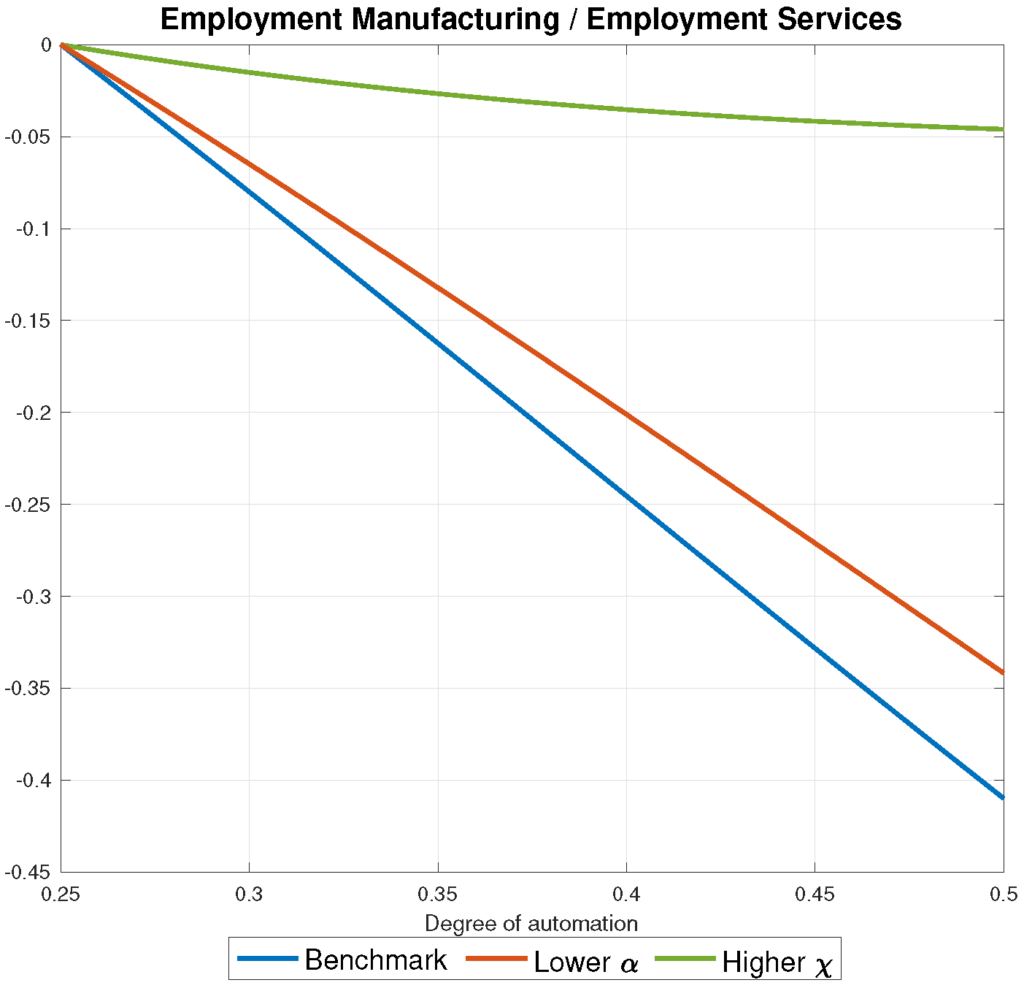

Two main parameters govern the strength of the sectoral reallocation of employment in the model: (1) the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor in the manufacturing sector α and (2) the elasticity of substitution between the outputs of the two sectors χ. Intuitively, in the first case, as α decreases, capital and labor become stronger complements in the production of the manufacturing good. As automation raises the return of capital for a given capital stock, in the long-run this leads to a higher capital stock in the steady state. The stronger the complementarity between the two inputs in manufacturing (i.e., the lower α), the higher is the relative demand for manufacturing workers. Therefore, the sectoral reallocation of employment due to automation is mitigated for lower values of α, as Figure 2 demonstrates.

Concerning the second parameter, we need to distinguish two different effects on production and employment in the service sector. Firstly, since automation leads to a higher accumulation of capital in the long run and, thus, to higher household wealth, this will lead to a higher demand for services, which is a normal good. Secondly, the stronger is the complementarity between the two goods in the economy, the higher is the increase in the demand for services. Consequently, a higher substitutability (i.e., a higher χ) between service and manufacturing goods mitigates the increase in the demand for services and, thus, the sectoral reallocation of employment, as Figure 2 shows.

Conclusion

To sum up, we build a general equilibrium model with an automatable and a non-automatable sector and labor market frictions that is able to rationalize the empirical evidence presented by Dauth et al. (2021) on (i) the substantial sectoral reallocation of employment and (ii) the null-effect on total employment. We show that our calibrated model can reasonably explain the empirical strength of the sectoral reallocation of labor. Furthermore, we analyze which key parameters govern the magnitude of this effect in the model.

An interesting extension of our model would be to include heterogeneous agents and capital-skill complementarity (see e.g. Dolado et al. (2021) and Santini (2021)). With that extended framework, one could study the interplay between automation, sectoral automation, and inequality. We leave this topic for future research.

References

- Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo. The race between man and machine: Implications of technology for growth, factor shares, and employment. American Economic Review, 108(6):1488–1542, 2018.

- Andrew Berg, Edward F Buffie, and Luis-Felipe Zanna. Should we fear the robot revolution? (The correct answer is yes). Journal of Monetary Economics, 97:117–148, 2018.

- Wolfgang Dauth, Sebastian Findeisen, Jens Suedekum, and Nicole Woessner. The adjustment of labor markets to robots. Journal of the European Economic Association, forthcoming, 2021.

- Juan J Dolado, Gergö Motyovszki, and Evi Pappa. Monetary policy and inequality under labor market frictions and capital-skill complementarity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, forthcoming, 2021.

- Jeffrey D Sachs, Seth G Benzell, and Guillermo LaGarda. Robots: Curse or blessing? a basic framework. mimeo, 2019.

- Tommaso Santini. Automation with heterogeneous agents: the effect on consumption inequality. mimeo, 2021.

Connect with the authors

Dennis Hutschenreiter is a PhD candidate in the IDEA Program (UAB and Barcelona GSE).

Tommaso Santini is a PhD candidate in the IDEA Program (UAB and Barcelona GSE)