Editor’s note: this article was originaly published in Spanish in the popular economics blog, Nada es Gratis, and is based on Kinga Tchórzewska’s PhD from the University of Barcelona. Her Job Market Paper was honorably mentioned in the third annual Nada es Gratis Job Market Paper awards.

Firms are often reluctant to invest in green technology. As for the reason why – they point to high fixed costs and the resulting capital market failure. However, instruments that could possibly address this problem, such as environmental investment tax incentives, are not very popular among regulators – even though they may offer an interesting alternative to environmental taxation or even investment subsidies, since tax incentives are easier to implement at the administrative level. Could Environmental Investment (EI) tax incentives be successful at encouraging green investment? And how do firms react to the modifications in existing EI tax credits with respect to employment and innovation decisions? I try to tackle those questions using the EI tax credit reform in Spain.

Spanish Environmental Investment (EI) Tax Credit

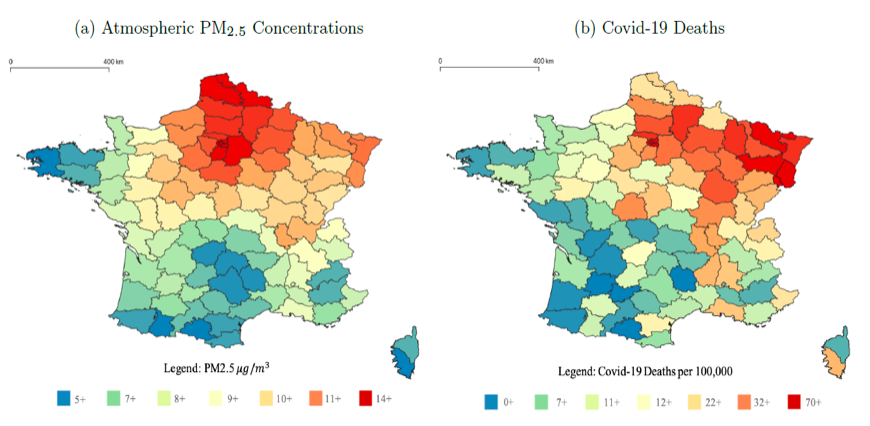

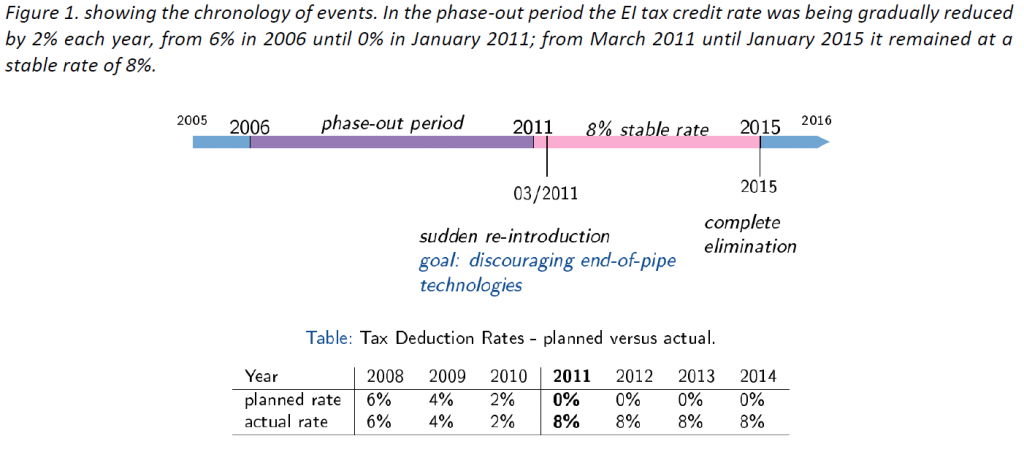

Spain is a very interesting country in which to study a large-scale national tax incentive program because the EI tax credit went through some unusual transformations over the years of its existence. The specific EI tax incentive analyzed in this paper was first introduced in 1996 at 10% of the firm’s level of investment and survived in such form until 2006, when its slow phase-out was announced. The phase-out was implemented as the then government believed that the tax incentive was mostly financing end-of-pipe technologies (which do not affect the production process but purely reduce the pollution level at the end of the production line e.g. filters and sulphur scrubbers) rather than cleaner production technologies, very often required by law already. The phase-out was then successfully continued until tax credit’s complete elimination in January 2011. Unexpectedly, in March of 2011, this tax credit was re-introduced for 4 more years at the stable rate of 8% investment level. It was possibly done to mediate the effect of the financial crises on the industrial sectors. Figure 1. shows the chronology of events and the expected versus actual rates of the tax credit.

What makes this EI tax credit reform especially interesting is that it generated a lot of confusion until the very last moment and while introduced in March 2011 – it was done specifically with the intention to favor cleaner production over end-of-pipe technologies. In the analysis, I focus on industrial firms as the main beneficiaries of the program and consider the time period between 2008 and 2014. In the first part, I compare firms’ behavior before and after the change in this policy instrument using difference-in-difference analysis. This will show if the modification of the tax credit discouraged end-of-pipe technologies as well as how the policy reform affected green employment. In the second part of the analysis, by using instrumental variable approach with difference-in-difference, I examine the proportionate effect of an increase in the amount of the tax credit. I study its proportional effect on firms’ investment, employment and R&D outcomes. Thus, I perform the first quasi-experimental econometric analysis of the effectiveness of EI tax credit at encouraging adoption of green technologies directly, but also indirect green employment and green R&D effects.

Results

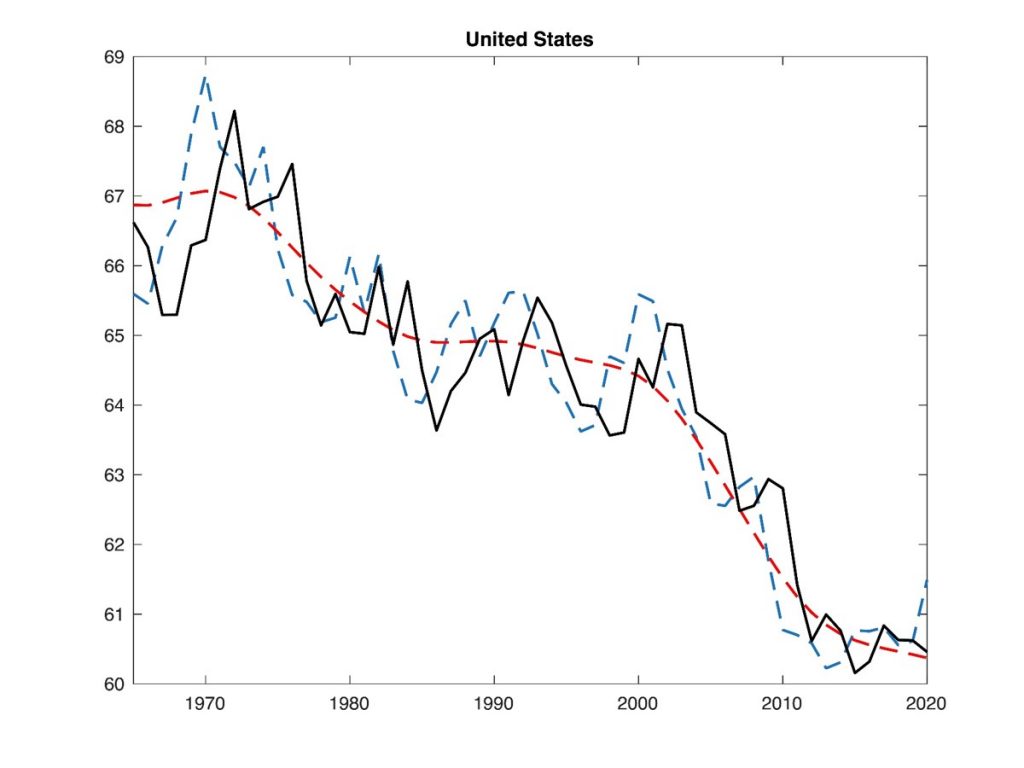

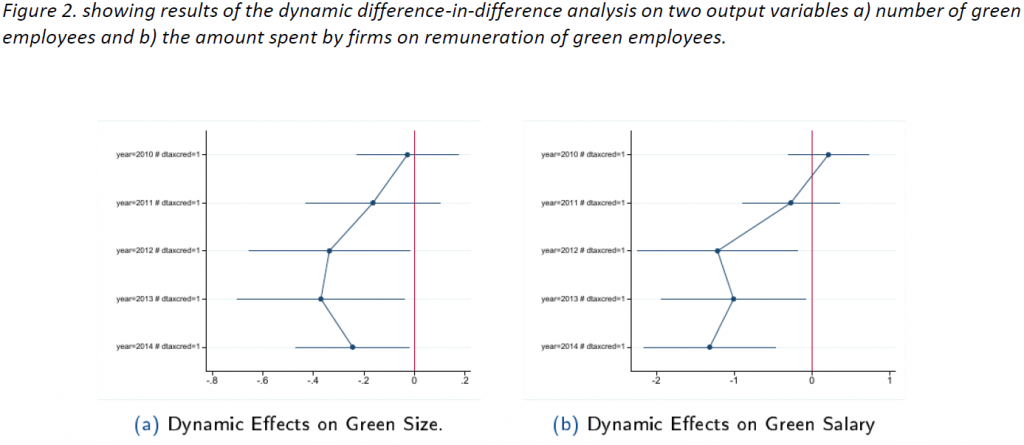

I find evidence that firms did in fact decrease their investment through the tax credit in the end-of-pipe technologies as a result of the policy change. This also includes the technologies specifically reducing air-pollution alone such as filters/sulphur scrubbers. We can, therefore, conclude that the modification was implemented quite successfully. That being said, there is no evidence to support the claim that this policy change led to an increase in the investment in cleaner production technologies. Unfortunately, the policy change also had a few unexpected indirect effects. It appears that firms reduced the number of green employees as well as the expenditure associated with the salaries of green employees, as can be seen in Figures 2a and 2b.

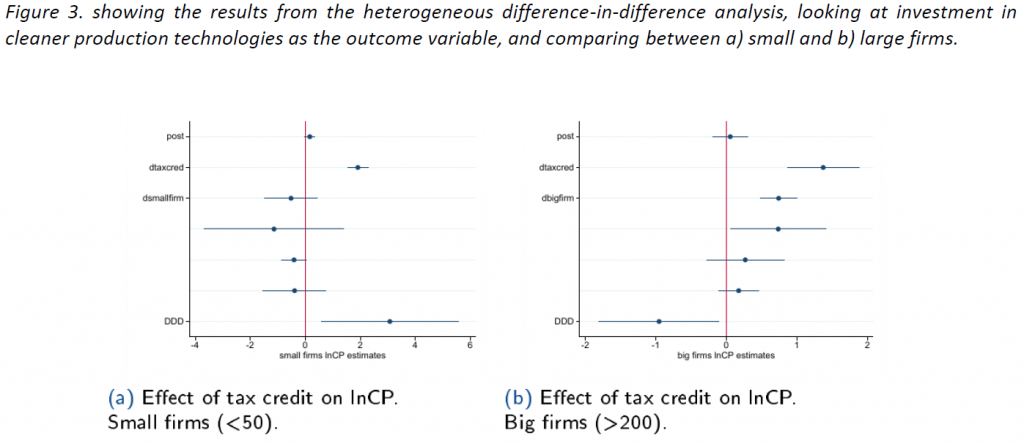

After performing the heterogeneous analyses, it is also clear that firms responded differently depending on their size – Figures 3a and 3b. More specifically, small firms seem to have benefited the most from the policy change, by considerably increasing their investment in cleaner production technologies. The opposite has happened to the large firms, who decreased their investment in the cleaner production technologies through the modified tax incentive.

By studying the proportional effect of the EI tax credit on investment outcomes it becomes apparent that Spanish environmental investment tax incentive was generally successful at inducing all types of green investment. This means that even during times of financial crises tax credit was drove firms’ green investment. However, they favored air-pollution-reducing over energy-efficient technologies, not necessarily end-of-pipe over cleaner production technologies, as per the concern of the government at the time. Additionally, I find further evidence that the increase in the amount of environmental investment tax credit results in a proportionate increase in the number of green employees and even private environmental R&D. Those indirect effects are quite hopeful, showing that a successful EI tax credit can also drive employment and create positive externalities through R&D.

Policy

This analysis provides a multitude of important implications for policy makers. Firstly, it encourages the usage of EI tax credits, which is also in agreement with previous literature, especially the work done by Ohrn (2019). However, this is in stark contrast to the decision of the Spanish government to eliminate this fiscal incentive from the Spanish Corporate Income Tax completely. This analysis supports its continuous use and perhaps even further modification, rather than a complete phase-out.

What we can learn from this green tax incentive is quite straightforward – adopting green depreciation incentives leads to increased business incentives and green employment outcomes, even during times of economic downturn. Additionally, the government can be successful at modifying the existing tax incentives, such that they discourage those technology choices that the central government considers undesirable. While the results clearly indicate that the tax credit should have been redefined even further so as to also encourage more investment in cleaner production technologies, this empirical work does not justify its complete phase-out. The fact that there is an increased investment in cleaner production technologies for smaller firms is also very important, as those are exactly the companies frequently faced with capital market failure – especially in the time of financial recession such as this one.

Of course, more research is needed to assess whether these types of incentives are the most efficient way to improve firms’ economic outcomes, and how the tax credit also affected their employees over the short- and long-run – especially after the complete elimination of the tax credit in 2015. Lastly, even given the financial burden that tax deductions and subsidies entail, they might still be economically justified in some cases. For instance, when positive externalities appear, such as increased green private R&D, which is the case here.

References

Ohrn, E. (2019). The effect of tax incentives on US manufacturing: Evidence from state accelerated depreciation policies. Journal of Public Economics, 180, 104084.

Connect with the author

Kinga B. Tchórzewska ’15 is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the ZEW – Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research. She is an alum of the Barcelona GSE Master’s in Economics.

This post was edited by Ashok Manandhar ’21 (Economics).